long-term population trends of colonial wading birds in the southern

advertisement

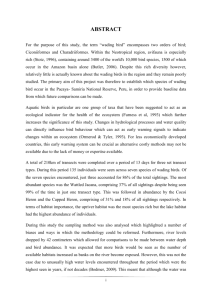

The Auk 112(3):613-632, 1995 LONG-TERM POPULATION BIRDS IN THE SOUTHERN TRENDS UNITED OF COLONIAL WADING THE IMPACT OF STATES: CRAYFISH AQUACULTURE ON LOUISIANA POPULATIONS BRUCE E. FLEURY AND THOMAS W. SHERRY Department of Ecology, Evolution, andOrganismal Biology,TulaneUniversity, New Orleans, Louisiana 70118, USA Al•sTl•C•r.--Long-term populationdynamicsof colonialwadingbirds(Ciconiiformes) were examinedusingdata from Audubon ChristmasBird Counts(CBC,1949-1988)and Breeding Bird Surveys(BBS,1966-1989).Winter populationsof Louisianawading birds increased dramaticallyover the 40-yearperiod,with the sharpestincreases occurringduring the last 20 years.Severalspeciespopulationsgrew exponentiallyfrom 1968to 1988.High overall positivecovariance wasfoundin the abundanceof the variousspecies overtime,andcluster analysisshowedthat the specieswith similardietaryrequirements and foraginghabitscovariedmoststronglyand positivelywith eachother.Trendanalysisof CBCandBBSdatafrom 1966-1989and 1980-1989showeda closecorrespondence betweenCBC and BBStrendsin Louisiana.Most speciesincreasedin Louisianaat the sametime as they declinedin Florida andTexas.Severalfactorsmightexplainincreases in populations of wadingbirdsin Louisiana, includinglong-termrecoveryfromthe effectsof humanexploitation, expansion of breeding populationsin more northernstates,changesin weather,recoveryfrom DDT and similar pesticides, and regionalmovements due to habitatlossin othercoastalstates.Thesehypothesesarenot mutuallyexclusive andmeritfurtherstudy.However,basedonseveralinferential linesof evidence,increasedacreagedevotedto crayfish(Procambarus) aquaculturein Louisiana appearsto be the mostsignificantfactorexplainingobservedpopulationtrendsin the state. First,populationsof colonialwading-birdspeciesthatusecrayfishwerecorrelatedpositively with the wild crayfishharvestin Louisiana,and even morestronglywith commercialcrayfish pond acreage.Second,the regularitywith which thesepondsare managedprovidesa more predictableforaginghabitatthan do correspondingnatural areas.Third, the useof crayfish pondsby wading birds peaksduring pond drawdowns,which may increasereproductive success by concentratingprey availableto wading birdsduring their nestingseason.Fourth, thosespeciesof wading birds that specializeon crayfishshowedthe greatestpopulation increasesand the strongestcorrelationwith crayfishpond acreage.These findings have importantimplicationsfor conservation and managementof Louisiana'swading-birdpopulations. Received16 May 1994, accepted 5 September 1994. ALTHOUGH WE LACK reliable nineteenth cen- tury data on colonial wading-bird populations (order Ciconiiformes), accounts from pioneer naturalists like Audubon document enormous coloniesthroughout the southernswampsand estuaries(Bent 1926). By the end of the nineteenth century, plume hunting had reduced many speciesto near extinction. Legal protection began in 1900 with the Lacey Act, which prohibited interstate commerce in illegally killed animals,followed by the Migratory Bird Treaty in 1916. The establishmentof wildlife refuges also helped protect wading-bird colonies (Parnell et al. 1988). Since their protection from plume hunters, many speciesof colonial wading birds have steadily increasedtheir North American populations, and expanded their rangesnorthward 613 and inland (Ogden 1978, Ryder 1978). However, wading-bird increaseshave not occurred in all regions. Whereas populations have increasedandrangesexpandedin the past30 years in someregionsof the United Statesfor species suchas Snowy Egrets,Great Blue Herons, and Cattle Egrets(Bockand Lepthien 1976, Ryder 1978, McCrimmon 1982, Larson 1982; Table 1), regionaldeclinescharacterize otherspecies, such as the Reddish Egret and RoseateSpoonbill (Powellet al. 1989,but seeOgden1991).Florida, for example,despitehaving a high historical populationdensityof mostspeciesof colonial wading birds (Root 1988), has witnessed reduced wading-bird populations due to prolongeddrought,estuarinedegradation,and human-induced hydrological changes in and around the Everglades (Bancroft et al. 1988, 614 FLœUR¾ ANDSHERRY Bancroft 1989). Ogden (1994) estimated that populationsof five speciesof wading birds in the Florida Evergladesdeclined by 93% between 1931-1946 and 1982-1989. [Auk, Vol. 112 TABLE1. Speciesof Ciconiiformesregularly seenon 343 Louisiana Christmas Bird Counts 1949-1988, and averagenumber observedper count. Such conflict- Aver- ing trends in populationsof colonial wading birdsmay even indicatelarge-scaleshiftsof re- age per Species count gional population centers. This diversity of population trends among regions and speciesindicatesthe need for in- American Bittern (Botaurus lentiginosus) Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) Great Blue Heron (Ardeaherodias) albus) creasedmonitoring, and for in-depth analyses Great Egret (Casmerodius Snowy Egret (Egrettathula) at national and regional scales.This need is par- Little Blue Heron (E. caerulea) ticularly apparentin Louisiana,where wadingbird populationtrends have been poorly docmented in the past,with breeding-colonydata only availablefor 1977,1984,and 1990(Portnoy 1977, 1978, Keller et al. 1984, Martin and Lester 1990, R. P. Martin 1991), and where wetland acreageis more abundant than in any other state. We review population trends of 15 speciesof colonial wading birds in Louisianaover the past 40 years, using data extractedfrom Audubon ChristmasBird Counts(CBC).We compareand contrastthese trends with state, regional, and nationaltrendsfrom BreedingBirdSurvey(BBS) data. We usepublished data to discussbriefly and evaluateseveralsuchfactors,namely longterm recovery from the effects of the plume 1.5 0.1 41.3 122.8 118.3 81.3 50.4 0.2 100.9 1.1 Tricolored Heron (E. tricolor) ReddishEgret (E. rufescens) Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis) Green-backed Heron (Butoridesstriatus) Black-crownedNight-Heron (Nycticoraxnycticorax) 13.0 Yellow-crowned Night-Heron (N. violaceus) 0.3 White Ibis (Eudocimus albus) 256.5 Glossyand White-facedibises(Plegadis falcinellusand P. chihi) 432.1 RoseateSpoonbill(Ajaiaajaja) 21.2 involves: tropical-fishfarms in Florida; catfish farms in California, Arkansas,and Mississippi; and fish farms in Europe(Draulans 1987b,Stickley andAndrews 1989,Boyd1991,Cezilly 1992, Stickleyet al. 1992).Wadingbirdscurrentlyare trade and other human exploitation, increased treatedas agriculturalpestsunder the Departwinter populationsdue to expandedrangesof ment of Agriculture'sAnimal DamageControl migratorywading birdsin morenorthern states, program. Depredation permits have been is- effectsof weather, recoveryfrom heavy pesti- sued in several states for lethal control of sev- cide use, competition, predation, habitat loss, and land-use changesin Louisiana due to the eral migratory bird species(including herons, egrets, pelicans, and cormorants)that feed at growth of crayfish (Procambarus) aquaculture catfish farms and other aquaculture facilities. (note: in Louisiana, the common name "crawIncreasedpopulationsof White Ibisesand Yelfish" is usedinstead of "crayfish"). low-crowned Night-Herons, which feed heaviContinueddeclinesin the quality and quan- ly on crayfish,are of particularconcernto Loutity of foraging habitat in natural wetlands due isiana wildlife biologists and farmers. Sound to drainage,pollution, and other human influ- managementpolicy for colonial wading birds enceshighlight the importanceof understand- in Louisianawill require detailed understanding how and why birds use artificial wetlands ing of the relationship between wading-bird suchasfloodedfieldsor aquacultureponds.The populationsand crayfishaquaculture,towards exponentialgrowth of commercialcrayfishpond which our analysesof wading bird population acreagein Louisianamay have directly contrib- dynamicsare an important first step. uted to increasesin Louisianawading-bird populationsby creatingnew high-qualityforaging METHODS habitats.Maddock and Baxter(1991) suggested that food limitation is a critical factor in egret CBC.--We used data from the annual Audubon reproductive success. The useof aquaculturepondsby wadingbirds alsoraisesimportant legal and conservationissues, both locally and internationally. The problemof bird predationin aquacultureponds ChristmasBird Count (CBC) to analyze winter ciconiiform populationtrendsin Louisiana.CBCsare held on a singleday between15 Decemberand 5 January. All birds seen within a 24.1-km (15-mi) diameter cir- cleare tabulated.In addition,observereffortis gauged July1995] Crayfish Aquaculture andWading-bird Populations 615 of birds countedas stronglyas would the addition of new countcirclesin wetland areas(Raynor1975,Morrison and Slack 1977, Bock and Root 1981). Therefore, we calculated the total number of birds observed di- vided by the number of countsheld in that year. There are several methodologicalproblems with CBC data. CBC data are not truly random samples, sinceregionsof high speciesdensityare favoredin the selection of count areas (Drennan 1981). CBC counts also are subject to error due to year-to-year differencesin weather and timing of the count (Falk 1979, Smith 1979, Rollfinke and Yahner 1990), and 0 1949 due to observer-reliabilityerrorsand volunteer turn1959 1969 1979 1989 over (Stewart 1954, Confer et al. 1979, Arbib 1981, Butcher1990). CBC data are most meaningful when they covermanyyearsand includea broadgeographic area because annual variations in weather and ob- server reliability become relatively less important (Bockand Root 1981, Ferner 1984, Butcher et al. 1990). The potential problem of speciesidentificationis not seriousfor wading birds, exceptfor the difficulty of discriminating between Glossy and White-faced ibises.We pooled thesespeciesinto a single category. Most CBC observations 1949 1959 1969 1979 989 Year Fig. 1. Number of Christmas Bird Counts held and total colonial wading birds counted, 1949-1988 (see Table I for completelist of species). by recordingthe total mileagecoveredand the total observationhoursby all parties(party milesand party hours, respectively;Butcher 1990). We used abundancedatafor the 16 speciesof ciconiiformsregularly seenin Louisiana(Table 1), alongwith observereffort recordedfor each count location.Analysesspanned the 40-yearperiod from 1949,the first year in which three or more countswere regularly held statewide, through 1988, for a total of 343 individual counts (number of countsper year are summarizedin Fig. Florida, Louisiana, Texas, and California, states which consistentlyrecordedthe highest wading-bird population densities in CBC counts (Root 1988). 1). Several methods have been used to normalize data in order to minimize of dark ibises in Louisiana were reported as White-facedIbises. To provide an independenttest of observedCBC trends,we analyzedBreedingBird Survey(BBS)data for the same speciesfor the periods 1966-1989 and 1980-1989(1966 is the first year in which BBStrends were reported).BBSsurveysare held in the summer, andreflectthe populationsizeof breedingbirds,while winter populations (CBC) reflect a combination of remaining (resident) birds plus wintering migrants. Several studieshave found closeagreement between CBC and BBSdata for a variety of species(Robbins and Bystrak 1974, Dunn 1986, Burdick et al. 1989, Butcher et al. 1990). BecauseBB$ data are compiled by roadsidecensus,they tend to underestimatepopulation sizesof colonialwading birds (Bystrak1981, Butcher1990).Wading-birdcoloniesoftenarelocated in remotewetlandsfar from highways.Nonetheless, the BB$samplesizesfor eachspeciesof wading bird usually exceededthe BBSminimum recommended size for dataanalysis,often by severalordersof magnitude (10 routes minimum per species;S. Droege pers. comm.). We analyzed BBSsurvey results for CBC variation due to differences in observereffort.Initially, we examinedtrendsstandardized per 10 party-hours,per 100 party-miles, and per countfor all wading bird speciesover the 40-year sampleperiod, and found that the method of normalization had surprisinglylittle effect on the observedtrends(unpubl. data).Given that colonialwading birdsaggregate,changesin observereffortwithin a countcircle would probablynot influencenumbers Dataanalysis.--Wecalculatedlinear regressions and exponentialcurvesfor eachspeciesbasedon the annual number of birds per CBC count. Data serieswith zero values were transformedby adding 0.1 to each datapoint for testingwith an exponentialmodel.The use of regressionto test hypothesesconcerningstatisticalsignificancein autocorrelateddata sets,such as annual censuses,violates the assumptionof independence(Bealand Khamis 1990).Therefore,we use the regressiondata only to demonstratethe obvious 616 F•.msa¾ tu'4DS•r•a¾ [Auk, Vol. 112 TABLE 2. Slopeand error (R2)valuesfor linear and exponentialbest-fitregressionmodelsof Louisianawinter wading-bird populations,basedon per-count ChristmasBird Count data, 1949-1988 (343 counts).Trends were not testedfor significance(seetext). 1949-1988 1968-1988 linear linear exponential -0.04 (0.09) 0.00 (0.00) 1.15 (0.34) -0.05 (0.06) 0.00 (0.02) 3.87 (0.83) 6.86 (0.40) 8.61 (0.40) 3.56 (0.09) 1.93 (0.19) 0.02 (0.26) 8.71 (0.45) 0.06 (0.35) 0.80 (0.20) 0.01 (0.10) 14.47(0.39) 18.55(0.37) -8.65 (0.09) 2.90 (0.09) 0.03 (0.15) 12.03(0.20) 0.06 (0.07) 3.02 (0.47) 0.04 (0.36) 0.00 (0.02) 0.00 (0.02) 0.01 (0.21) 0.03 (0.36) 0.04 (0.28) 0.05 (0.46) 0.02 (0.18) 0.02 (0.32) 0.11 (0.84) 0.04 (0.59) 0.00 (0.00) 0.00 (0.01) 0.04 (0.79) 0.04 (0.64) 0.05 (0.62) -0.01 (0.02) 0.02 (0.11) 0.03 (0.22) 0.05 (0.45) 0.02 (0.24) 0.02 (0.09) 0.01 (0.14) 0.10 (0.62) 0.04 (0.41) White Ibis 23.22 (0.49) 56.21 (0.59) 0.07 (0.48) 0.07 (0.66) Glossyand White-facedibises RoseateSpoonbill 22.92 (0.30) 1.35 (0.29) 55.21 (0.46) 1.37 (0.07) 0.05 (0.21) 0.08 (0.56) 0.06 (0.41) 0.06 (0.24) Species American Bittern Least Bittern Great Blue Heron Great Egret Snowy Egret Little Blue Heron Tricolored Heron ReddishEgret Cattle Egret Green-backedHeron Black-crownedNight-Heron Yellow-crowned Night-Heron long-rangetrend in the populationdensitiesof these species,rather than to test hypothesesof statistical significanceof trends.We smoothedpopulation data with a three-yearsliding averagefor graphicpresentation only (Raynor 1975). The squaredcorrelation coefficientof the fitted curve (R2) for linear regressionsof nonsmootheddata approachedor exceeded 0.50 for the most abundantand rapidly increasing species(Table 2). To allow direct comparisonof BBSwith CBC data, we calculated CBCtrends(annualpercentchangeper year) for each speciesfor 1966-1989 and 1980-1989. These two periods representedthe most recent BBS data available. BBS trends are calculated with a route- 1949-1988 1968-1988 exponential pressedthe resultingtrendaspercentchangeper year (100[trend- 1]). We assessed covariationof temporaltrendsamong speciesfor the 40-yearCBCdataset using Schluter's (1984) covariance test. This test is based on the ratio (V) of the variance in the total number of individuals per sample(ST2, all speciescombined)to the sum of the variancesof the individual speciesdensities(•.s,2). Bythe null hypothesisof no covariationin population trendsamongspecies,the conditionalexpectedvalue of ST2is equalto 2i s,2,giving V the value of 1. In this case,the variance in total abundancefor all species from year-to-yearcanbe completelyexplainedby the sum of the variancesin density of each individual regressiontechnique,which estimatesmediantrends using a bootstrapanalysis to estimate trends from species. We calculated Schluter's index of association(W), random subset samples (Geissler and Noon 1981, Geissler 1984, Geissler and Sauer 1990). Our trend which is equal to VN (N equalsthe number of sampies) and analysisof CBCdatais basedon one estimateof species abundancefor each year (per-count data). We fitted a simple linear regression log•(count,+ 0.5) = year,(log•[b]) + log•(a), (1) where e is the baseof the natural logarithms,count• is the number of birds observedper count in year/, b is the slope of the fitted regression,and a is the y-interceptof the fitted regression. We addedthe constant0.5 to insurea defined logarithmfor countsof zero.We calculatedthe trend fromthe antilogof the slopein this regression(Holmesand Sherry 1988): Trend = e(løs'l'-ø-ssE), (2) where b is the slopeand SE the standarderror of the slopeof the regressionon logarithmicper countdata. The SE term correctsfor the asymmetryof the lognormal distribution (Geissler 1984). We then ex- W=VN=ST2N/.•. s?, (3) where ST 2=(l/N)• (Tj- t)2, (4) s, 2=(l/N)• (X,j - t,)•. (5) J and ] Tj is the total densityof birdsin yearj, t is'the mean densityof totalbirdsacross all j years,X•jequalsthe densityof speciesi in yearj, and t•equalsthe observed meandensityof speciesi amongall j years.If the ratio V isgreaterthanone,species tendto covarypositively July1995] Crayfish Aquaculture andWading-bird Populations and, if V is lessthan one, speciestend to covarynegatively. W is approximately chi-squaredistributed, with n degreesof freedom(Schluter1984). We calculated Pearson correlation coefficients for each possiblepair of speciesover the 40-year CBC data set.We then clusteredall specieson the basisof their correlationcoefficients,using a maximum-linkagealgorithm to summarizesimilaritiesin abundance patterns. For example,from 1966 to 1989,breeding populations (BBStrends) showed a higher rate of increase than did winter populations (CBC trends) in White-faced Ibises, RoseateSpoonbills, Snowy Egrets,Great Egrets,and Yellowcrowned Night-Herons, while CBC data indicated greater increasesthan BBSdata for BlackcrownedNight-Herons and Great BlueHerons. BBStrendsby state.--A comparisonof Louisiana BBS trends with RESULTS Sixteencolonialwading bird specieswere observedregularly on LouisianaChristmascounts (Table 1). Winter population sizesfor mostspeciesincreased(Table2) basedon per count CBC datasmoothedwith a three-yearsliding average (Fig. 2). Slopesof linear regressions(abundance per year) from 1949 to 1988, based on nonsmoothedper-countdata, were positive for 13 617 those of other states con- taining large wading bird populations (Florida, Texas,and California) revealed regional differencesin population trendsduring the pasttwo decades(Table 3). Florida'swading-bird populations, unlike those in Louisiana,appear to be declining. Only the Snowy Egret,Little Blue Heron, and Green-backed Heron populations increasedfrom 1980-1989.Colony censusdata, however, indicate that Florida'sSnowy Egret population may have declined sharply during of the 16species (Table2). Species with highest this period (Ogden 1994).Furthermore,popuslopeswere White Ibis,Glossyand White-faced lationsof 10 Florida speciesdeclinedmore rapibises, Cattle Egret, Snowy Egret, and Great idly from 1980-1989than 1966-1989.Most speEgret; other specieswith positive slopeswere cies of Texas wading birds also declined, esLittle Blue Heron, Tricolored Heron, Roseate peciallyin the lastdecade.Severalof the species Spoonbill,GreatBlueHeron, and Black-crowned that remained stable or declined from 1980Night-Heron. LeastBitternsand American Bit- 1989 in Florida or Texas simultaneously interns had a slopenear zero. The relative rarity creasedin Louisiana,namely the White Ibises, of the Green-backedHeron, ReddishEgret,Yel- Glossy Ibises, White-faced Ibises, Yellowlow-crowned Night-Heron, American Bittern, crowned Night-Herons, Black-crownedNightand Least Bittern precludes drawing any firm Herons, and Tricolored Herons. California wading-bird populations showed the largest conclusionsregarding these species. When we restricted analysesto the last 20 number of significantincreasesof the statesexyears (1969-1988), most species(11 of 16) in- amined,particularlyin 1980-1989for the Whitecreasedexponentially, based on a somewhat facedIbises,Cattle Egrets,Snowy Egrets,Great better fit to an exponential than a linear re- Egrets,and Black-crownedNight-Herons. Community-level analyses.-The Schluter(1984) gression(i.e. larger R2;Table 2). In particular, populationsof Great Blue Herons, White Ibises, covariance test assesses covariance within a community or assemblage.This test revealed a Great Egrets, Black-crowned Night-Herons, Snowy Egrets, Cattle Egrets, Yellow-crowned high degreeof positive covariancein 40-year Night-Herons, and Glossy and White-faced CBC population trends in Louisianaamong all ibisesincreaseddramaticallyfrom 1968to 1988 16 species(W = 127.15,df = 40, P < 0.001). We believe that this covariance reflects a similar (Fig. 3). response among species pairs to changing ecoComparison of CBC and BBStrendsin Louisiana.--Most Louisiana BBS trends closely par- logical conditions, particularly the quality of alleled LouisianaCBC trends during the 1966- foraging habitat (seeDiscussion). We clusteredspeciesbased on speciespair1989 time period in terms of their magnitude and direction (Table 3). Both BBSand CBC trends wise correlation coefficientsof population sizes showthat mostLouisianapopulationsincreased over time, using a complete-linkage method from 1966to 1989,especiallyWhite Ibises,Glossy (Sneath and Sokal 1973, Bock and Root 1981, and White-faced ibises, Roseate Spoonbills, Holmes et al. 1986).The resulting tree diagram Snowy Egrets,Cattle Egrets,and Great Egrets. (Fig. 4) showsthat the Great and Snowy egrets Not all Louisiana BBS trends corresponded (diurnal visual feeders on primarily fish and with the CBC trendsin thesetwo time periods. crayfish) clustered most closely with one an- 618 FLEURY AND SHERRY a. Great Blue [Auk, Vol. 112 Heron b. Green-backed Heron 4 100 3 2 1 194919•9 1969 19•79 '1'989 c. Little Blue 1949 19'•919'6919'79'1'989 d. Cattle Egret Heron 400 4OO 3OO 300- 200 0 0 1949 1959 1969 1979 1949 1989 1959 1969 1979 1989 1979 1989 f. Great Egret e. Reddish Egret 1.5 5OO 1.0. 4OO 300 200 0.5. 100 0.0 ........ , .... ,.. 194919'591969 1979'1'989 Year 0 1949 1959 1969 Year Fig.2. Numberof individualsof 16speciesof colonialwadingbirdsper LouisianaChristmasBirdCount, 1949-1988.Curvesare least-squares exponentialfunctionsfit to smoothedper-countdata. other, indicatinggreatestsimilarity of population trends. The ibises (diurnal tactile feeders on primarily crayfish)alsowere closelycorrelated with one another,aswere the two nightheron species(nocturnal visual feederson pri- marily crayfish).The Great Blue Heron clustered most closelywith the ibisesand egrets. The Little Blue Heron and the two bitterns were dissimilar from the other speciesin population changeswithin Louisiana. July1995] Crayfish Aquaculture andWading-bird Populations h. g. Snowy Egret 619 Tricolored Heron 2OO 6OO 4OO loo 0 1949 i. 1959 1969 1979 1989 1949 Black-crowned Night-Heron j. 1959 1969 1979 Yellow-crowned 1989 Night-Heron 1.2 0.8 0.6 0A 0.2 1949 k. 1959 Least 1969 1979 1989 1949 Bittern 0.5 1. 1959 American 1969 1979 1989 Bittern 4 3 2 1 Year Year Fig. 2. Continued. DISCUSSION es demonstratedby CBC data were not an artifact of data-collection methods. The use of the Louisianawading-birdpopulationtrends.--CBC per-countmethodfor normalizingCBCdatafor datashowincreasingwinter populationsof most colonial wading birds only removed the exspeciesof Louisianawading birds. The increas- podential trend shown in observer effort over 620 FLEUR¾ AIqDSHERRY m. Glossy and Whim-facedibises 2OO0 [Auk,Vol. 112 density species,however, in two individual countsat oppositeends of the state (New Orleans and Sabine NWR) from 1954 to 1988 showedthe sametrendsasin the completedata set (Fleury unpubl. data). Furthermore,Louisiana BBS trends generally support the observed CBC trends for the same time periods (Table 3). The Schluter covariance test suggeststhat someecologicalfactorswere affectingmostspeciessimilarly,resultingin a strongand positive covariancebetweenthem. Closelyrelatedspecies,however,need not covaryin their popu- 0 1949 1959 n. White 1969 1979 1989 lation fluctuations, and BBS data from areas out- side of Louisianasuggestdifferent population trendseven in congenericpairsof species(Table 3). Interspecificcompetitionis one causeof Ibis negative values of W in some communities (Schluter 1984), but the positive value of W in our data indicate that interspecificcompetition 1200 was not an important factor influencing population trends in these wading-bird species. Moreover, these speciesclustersare similar to thoseproposedby Kushlan(1978)basedon resourcepartitioning in South Florida wadingbird communities.Many environmental factors could account 1949 1959 1969 1979 1989 o. Roseate Spoonbill for the trends we have docu- mented.As we arguebelow, however, the most likely single factoris variation in food supply. Stateandregionalpopulation trends.--Analyses of BBSdataprovedusefulherein corroborating many CBC trends (Table 3), and suggesteda complexregionalpatternof shiftingrangesand population centers for colonial wading birds. Our studysuggests the possibilityof large-scale regionalchangesin populationcentersof wading birds along the Gulf Coast.Many of the decreases in wading-birdpopulationsin Texas and Florida indicatedby BBSdatawere contemporaneouswith increasesin Louisianapopu- lationsof thesespecies.Frederickand Spalding (1994)describeda generalpatternof population shifts of White Ibises from Florida to other areas o 1949 1959 1969 Year 1979 1989 Fig. 2. Continued. in the Southeast.A decline in nesting White Ibis in the Carolinasalsoseemsto parallelgains in Louisiana'sWhite Ibis population(Frederick et al. in press).R. P. Martin (1991) noted that for 8 of the 11 wading-birdspeciesknown to nest in the Louisiana coastal zone, the state now accounts for over 25% of the known U.S. coastal breeding populations.Further study will be the sametime period(Fig. 1). SomeCBCcounts neededto determinewhether the observedpataddedin the last decadeare in areasof high terns are causedby regional populationshifts, bird densityand,therefore,mightaffectthecal- or are the result of complexlocal population culatedtrends.A separateanalysisof sixhigh- changes. July1995] Crayfish Aquaculture andWading-bird Populations a. Great Blue Heron 621 b. Great Egret 500 100 4OO 300 200 100 0 0 1968 1978 1968 1988 '19s78 1988 d. Yellow-crownedNight-Heron c. Black-crownedNight-Heron 1.2 8O 1.0- o •) 0.80.60.4- 0.20.0 0 1968 1978 1968 1988 e. Glossyand White-faced•ises '19•8 1988 L White Ibis 2000 1200 6 2OO 0 1968 0 1978 1988 1968 1978 1988 Year Year Fig.3. Exponential-growth models of selected species of colonial wadingbirdsin Louisiana Christmas BirdCounts,1968-1987(numberper count,smoothed). Wadingbirdsandcrayfishponds.--Wefound a strongpositivecorrelationbetweenseveralspeciespopulationsof wadingbirdsand the avail- between 1968 and 1987. We list several lines of evidencebelow to support the hypothesisthat increasedacreagedevoted to crayfishaquaculability of both wild and pond-raisedcrayfish ture is a dominant ecologicalfactorinfluencing 622 FLEURY ANDSHERRY [Auk,Vol. 112 TABLE3. ChristmasBird Count (CBC) trends for Louisiana, and Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) trends for Louisiana,Florida, Texas,and California (percentannual change).Dash (--) indicatesno data reported. Louisiana Species Florida CBC BBS BBS Texas BBS California BBS 1966-1989 American Bittern Least Bittern Great Blue Heron GreatEgret SnowyEgret Little Blue Heron Tricolored Heron ReddishEgret CattleEgret Green-backed Heron 0.4 0.4 8.8 -1.7 1.7 9.7 15.1 15.5' 24.8 1.2 7.7 -2.2 8.4 3.0 11.1 -0.2 0.9 -1.1 1.1 0.6 3.6** -9.4 17.0 0.4 0.7 -2.0 - 1.2 -12.3'** -0.8 1.2 -2.3 -0.1 0.0 2.7 12.4'** 11.1'** --- -19.1' 4.0 2.0 - 2.7 Black-crownedNight-Heron Yellow-crownedNight-Heron 20.3 4.0 3.3 9.1 - 11.6 0.2 - 0.2 -0.2 11.1 -- White Ibis White-faced 25.4 24.9 a 18.5 58.8 -1.2 -- 10.1'* - 0.9 -26.8 * * * 24.9a 17.5 -36.4 -8.9 132.3 Ibis GlossyIbis RoseateSpoonbill 1.0 3.2 -1.9 -1.3 5.7 * * * --- 1980-1989 American Bittern Least Bittern Great Blue Heron GreatEgret SnowyEgret 3.7 7.5 Little Blue Heron Tricolored Heron ReddishEgret CattleEgret Green-backed -3.3 -0.6 4.8 Heron ---2.4 10.6 49.6 -9.7 6.9 6.6 6.1 3.4 -3.2 -0.7 -2.0 - 11.4 - 11.0 1.0 -- 15.0 -7.0* -1.1 -5.6 - 16.8'* * - 1.0 3.2 -6.5 -10.8'* -- 3.0 -4.7 -3.9 2.5 12.3'** 13.0'** --- -25.4* 2.6 18.3 7.7 White Ibis White-faced 13.5 8.0 a 2.2 4.7 -3.3 -- 0.9 - 21.2* * * -44.9* * * 8.0a 16.6 -14.6 -20.5 0.9 0.9 - 16.9'* --- GlossyIbis RoseateSpoonbill - 15.1 - 1.2 10.1 8.9* 1.0 --3.1 Black-crownedNight-Heron Yellow-crownedNight-Heron Ibis 5.8 21.2'* --2.7 4.2 21.9 -- *, P < 0.10; **, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.01. Combineddata for Glossyand White-facedibises.Most birds reportedas White-facedIbis. the strongrecentgrowth trendsof many Louisianapopulationsof wading birds. The Atchafalayabasinprovidesabundantfish, crayfish,frogs,and otherprey for wadingbirds (Blades1974,Gary 1974a).This rich food supply, however,fluctuatessharplyfrom year to year dependingon weather (McSherry 1982, Huner 1990).The crayfish-aquaculture industry providesfarmerswith a reliable alternativeto an unpredictableswampharvest(Gary 1974b, McSherry1982),and the regularitywith which pondsare managedalsomakescrayfishponds a morepredictablefoodsourcefor wadingbirds than comparablenatural foragingareas.Wellmanagedpondsmimic the naturalhydrologic patternsthat promotecrayfishgrowth in the extensive marshes of southern Louisiana. The hydrologicalcyclein crayfishpondsis managed slightly out of phasewith, and ahead of, the naturalwetlandshydrologicalcycle(Fig. 5). This minimizes the overlap between the pond harvestand the wild harvest,and preventsan overabundanceof marketablecrayfish,which would significantlyreduce the market price (Martin 1979,McSherry1982,Huner and Romaire1990). Louisianacrayfishlandingsfrom 1949to 1987 were significantlyand positivelycorrelatedwith populations of Great Blue Herons, Yellowcrowned Night-Herons, Black-crownedNightHerons,GreatEgrets,Snowy Egrets,White Ibises,and Glossyand White-facedibises(Table4). All of thesespeciesare known to feed on crayfish (Table 5). We found correlationsnearly twice as high, July1995] Crayfish Aquaculture andWading-bird Populations Little Y-c Blue 623 Heron Night-Heron B-c Night-Heron Roseate Spoonbill Great Egret Snowy Egret Great Blue White Ibis Heron Glossy and Whitefaced ibiseS Green-backed Heron Trlcolored Heron Reddish Egret Cattle Egret Least Bittern American Bittern i 1.0 I I 0.8 I I I I 0.6 I 0,4 Pearson I 0,2 r Fig. 4. Clusteranalysisof speciespairwisecorrelationcoefficients basedon per-countCBC data, 19491988. however,betweenthesesamespeciesof wading birdsand the total acreagedevotedto commercial crayfishpondsin Louisiana.Crayfishfarm pondsincreasedfrom 99 ha in 1949to over 284, 165 ha in 1991 (W. Lotto pets. comm.), but reliabledatafor crayfishpondsareonly available from 1968 to date (Table 4). Many speciesof wading birds feed regularly in crayfishponds, especially Yellow-crowned Night-Herons, White Ibises,Great Egrets,Snowy Egrets,and on, Black-crowned Night-Heron, Yellowcrowned Night-Heron, White Ibis, Glossyand White-facedibises,Great Egrets,and Snowy Egrets(Table 4). These same specieshad the highestproportionof crayfishin their adult or nestling diets, and were among those increasing mostrapidly in LouisianaCBCor BBStrends fledglng Wading-bird stage J Little Blue Herons (Table 6; Huner 1994, Martin and Hamilton 1985; Huner 1976 presentation Wading.birdI at EcologicalSocietyof America;Fleury pers. inenbatlon stage] obs.). More importantly, species-specificdietary patternsof Louisianawading birdssupportthe hypothesisthat crayfishaquacultureand wading-bird populationincreasesare causallyrelated (Table 5). Populationgrowth of species that rarely feed on crayfish,including Cattle Egretsand RoseateSpoonbills,are poorly correlatedwith crayfishpondacreage(Tables4 and 5). Wading-bird specieswhose population in- creases from 1969-1989correlatedmosthighly with crayfishacreagewere the GreatBlueHer- I Wild crayfish I harvest Pond-raised crayf".b ] [Pond-rai.d Drawdown or ] crayfishponds] Jan Feb Mar Apl May June July Ang Sept Oct Nov • Fig.5. Temporalrelationshipbetweenwading-bird breedingcycle, crayfishpond harvest,and crayfish pond drawdown. 624 FLL•.rR¾ ANDSHERRY [Auk, Vol. 112 T^BLE4. Pearsonproduct-momentcorrelationof wading-bird populations(per count CBC, 1968-1987)with crayfishaquaculturepond acreage,wild crayfishharvest(in pounds),and rice field acreage(harvested). a 1968-1987 crayfish (df= 18) Species American Bittern Least Bittern Great Blue Heron Great Egret SnowyEgret Pond -0.20 0.10 0.90'* 0.63** 0.63'* Little Blue Heron Tricolored Heron -0.26 0.44 ReddishEgret Cattle Egret 0.46* 0.38 Green-backed Heron Wild 1949-1987 wild crayfish (df = 37) 1968-1987 rice -0.12 -0.01 0.45* -0.21 0.08 0.52* * -0.14 -0.02 - 0.55 0.35 0.44 0.56** 0.61** -0.30 - 0.37 -0.17 0.25 0.18 0.44'* 0.33 - 0.18 0.02 - 0.02 0.29 0.39' 0.19 - 0.21 0.40 0.32 0.55' * - 0.24 Black-crownedNight-Heron Yellow-crownedNight-Heron 0.89'* 0.68** 0.56' 0.45* 0.47'* 0.25 - 0.59 -0.07 White -0.45 0.72** 0.42 0.44** Glossyand White-facedibises Ibis 0.75** 0.34 0.60** -0.40 RoseateSpoonbill 0.35 0.31 0.53** -0.14 *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. ßCrayfishpond acreagedatafrom W. Lorio (pets.comm.)and J. Huner (pets.comm.).Data for wild-crayfishlanding datafrom the National Marine FisheriesService.Rice-acreage datafrom Fielderand Nelson(1982)and Universityof New Orleans(1990). from 1966to 1989(Tables3 and 5). A few species are exceptionsto this pattern. Great Blue Herons,for example,consumerelatively few crayfish, but their numberscorrelatestrongly with of prey in shallowwater, governedby the seasonaldrying rate, is an important requirement for efficient wading bird foraging in the Everglades,particularlyfor tactilefeeders(Kushlan crayfishpond acreage.They may benefitfrom et al. 1975). A rapid drying rate ensuresthat otherprey,suchastheabundantsmallfishfound prey items will be concentratedin sufficient density in small pools (Bancroft et al. 1988). in mostfarm ponds. Seasonalpatternsof crayfish-pondusageby While this relationshipmay not hold generally Louisianawading birds also strongly support for wading birds outsidethe Everglades(Fredthe hypothesisthat crayfishpondscontribute erick and Spalding 1994),the timing of breedto population growth by increasingreproduc- ing cycleand ponddrawdown in Louisianasugtive success(Fig. 5). Wading birds use crayfish gestsa similarpattern,particularlyfor the White ponds throughout the year, but usage peaks Ibis. White Ibisesrely heavily on crayfishfor their nestling diet (Bildstein et al. 1990, Bildtwice annually (Huner 1983,Martin and Hamilton 1985).The firstpeakoccursin winter,when stein 1993), and abandonment and failure of the pondsare filled and adult crayfishemerge White Ibis nestsis closely related to low prey from their burrows with broodstock. A much density and excessiverainfall (Frederick and higher peak occurs in May and June, when Collopy 1989b). Because drawdowns occur at different times ponds are drained following the commercial harvestand wading birds are establishingnests on different farms throughout southern Louiand feeding nestlings(Martin 1979;Fig. 5 and siana, crayfish farms create a landscape-level Table 6). seriesof patchesof high prey density. These Crayfishpond drawdown simulatesthe dry- landscape-levelpatchesare analogousto those ing of surfacewater in natural wetlands,and tracked by wading birds foraging in natural consequentconcentrationof prey,althoughthe wetlands.Colonialwading birdsare well adaptdrying period in crayfish ponds is relatively ed behaviorally to track spatially and temposhort.During the pond-drawdownphase,cray- rally patchyfood supplies(Kushlan1976,Erwin fish that have not yet burrowed are concen- 1983, Kushlan 1986,Bancroftet al. 1994). If wadtrated in shallow water, along with other crus- ing-bird populations are ultimately food limtaceans,fish, amphibians,and aquatic insects ited, the addition of a new sourceof prey that (Huner 1983, 1994). The natural concentration is readily availableaswell asspatiallyand tern- July1995] Crayfish Aquaculture andWading-bird Populations 625 T^nI,E 5. Percentageof crayfishand other crustaceans in diets of colonial wading birds. Where range is given, first referencecited correspondsto lower value, with "ad" referring to adult bird diet, and "j" referringto juvenilebird diet. Percentvaluesrepresentratiosof numbersof crayfishto total numberof prey items.Valuesmarked"mass"representdietary percentageby massor volume. Percentcrayfishin diet of Species American Adult Bittern 19-25 Least Bittern Great Blue Heron I0 a 9-14' Great Egret Juvenile Source Palmer 1962 (ad), Sprunt and Chamberlain 1949 (aS) Palmer 1962 (ad) Palmer 1962 (ad), Sprunt and Chamberlain 3O 9 (mass)a,b 1949 (aS) Recher and Recher 1980 (ad), Howell 1932 (j) Snowy Egret 16 (mass)-39 0.7-3 Recher and Recher 1980 (ad), Telfair 1981 (ad), Jenni 1969(j), Howell 1932(j) Little Blue Heron 11-73 5-8 Niethammer and Kaiser 1983 (ad), Telfair 1981(ad), Howell 1932(j), Rodgers1982 (j) Tricolored Heron 2a-20 0-2 Sprunt and Chamberlain 1949 (ad), Palmer 1962(ad), Jenni 1969(j), Howell 1932(j) ReddishEgret Cattle Egret 2 (mass)c 0 0 Recher and Recher 1980 (ad) Palmer 1962 (ad), Telfair 1981 (ad), Jenni 1969,1973(j) Green-backed Heron Black-crownedNight-Heron Yellow-crowned Night-Heron 1-20 Niethammer and Kaiser 1983 (ad), Palmer 1962 (aS) 8 22 74-97' White Ibis 52-72 (mass) GlossyIbis _a White-faced Ibis RoseateSpoonbill 46 37-40 Palmer 1962(ad), Howell 1932(j) Niethammer and Kaiser 1983 (ad), Riegner 1982 (ad) Kushlan and Kushlan 1975 (ad), Kushlan 1979 (ad), Howell 1932 (j) Sprunt and Chamberlain1949(ad), Baynard 1913(j), Howell 1932(ad,j) 35 Palmer 1962 (ad) _c Palmer 1962 ßDietary reports include other crustaceansin total. bDiet reportedas 100%prawns. cFor thesespecies,Palmer (1962)describeddiet as mainly fish, with a few crayfishor other crustaceans. dSpruntand Chamberlain(1949)describeddiet as"for the mostpart'' crayfishand grasshoppers. Howell (1932)notedthat crayfishcomprised a "considerable percentage"of the diet. porally staggered from natural food sources for example,winter in ever-increasingnumbers should have a substantialimpact on reproduc- to feed in 222,390ha of catfishfarm pondsscattive successof speciesusing this resource.Dou- teredacrossMississippi's Delta region.Thisnew ble-crested Cormorants (Phalacrocoraxauritus), foraginghabitat may have contributedto a 25% TABLE 6. Wading birds observedduring drawdownof crayfishpondsat the Universityof Southwestern Louisiana's Crawfish Research Center, 1992-1995. Annual census is taken near end of drawdown when pondbottomspartlyexposed, andrepresents peakannualbird countrecordedon 20-hafarm-pondcomplex. Species 1992 Great Blue Heron Great Egret Snowy Egret 0 211 445 Little Blue Heron Tricolored Heron 4 2 1993 1994 2 26 192 4 2 1995 I 0 499 273 84 439 18 42 5 -- Black-crownedNight-Heron Yellow-crownedNight-Heron --- 2 I -8 -1 White Ibis 104 0 225 85 Total 766 229 1,024 656 626 FLEUR¾ m,•VS•-mRR¾ [Auk, Vol. 112 increase in the species' northern Great Lakes and other pesticides,competition, predation, a breedingpopulation(Conniff 1991,A. May pers. responseto changingweather, and changesin comm.). The explosive growth of California's habitat. The AOU calculated that some 5,000,000 birds White-faced Ibis population (Table 3) may be attributable to its ability to forage successfully of all specieswere killed each year by plume in the irrigatedfieldsthat havelargelyreplaced its former foraginghabitatof backwatersloughs and flooded meadows (Bent 1926, Small 1975, Bray and Klebenow 1988). Foodlimitation may be especiallycriticalduring the nestling phase of the annual breeding cycle(Rodgersand Nesbitt 1979,Newton 1980, T. E. Martin 1987, 1991). Mortality in wading birds peaks in the first two weeks of life, and remainshigh for fledglings(Kushlan1978).Kahl (1963) reviewed mortality in several wadingbird species,and found that first year mortality ranged from 61 to 78%. Abundant food supply may affectpopulationgrowth by improving the survivorship of both nestlings and newly fledged young (Powell 1983, Mock et al. 1987). Crayfishpondsalsomay increasefledglingsurvival by assuring inexperienced fledglings a steadysupplyof easilycapturedprey while they learn to forage. Juvenile wading birds are less effective foragers than adults in the same hab- hunters for the fashion trade from about 1875 through the early 1900s(Buchheisterand Graham 1973),althoughthe questionableaccuracy of early population estimatesmakesit difficult to judge the true impact of the plume trade on wading birds (Robertson and Kushlan 1974, Frohring et al. 1988,Ogden 1994).Exploitation of wading birds for plumes, eggs,and food was an important source of mortality throughout the southern United States as late as the 1930s for severalspecies(Powell et al. 1989),and some illegal harvestingprobablycontinuesto this day. Most wading-bird species,at least in the Gulf coaststates,had probablyrecoveredfrom plume hunting by the 1930s (Ogden 1978, Bancroft 1989). Therefore, it is unlikely that the post1940s increaseswe have documented are primarily the result of recovery from the plume trade or other human exploitation. Could the observedpopulation increasesreflect expanding ranges of migratory wading itat (Recher and Recher 1969, Bildstein 1983, birds outside of Louisiana?Great and Snowy 1993, Draulans 1987a, Cezilly and Boy 1988, egretsare expandingtheir rangesto the north, Frederickand Spalding 1994). Farm pondsalso possibly reoccupyingportions of their range have fewer alligators (Alligatormississippiensis)occupiedprior to plume hunting (Ogden 1978, and other avian predators than natural wetRyder 1978).Great Blue Herons have increased lands,perhapsbecausethere is little or no cover in northern New York, perhaps in responseto reforestation of abandoned farmland (Mcaround farm ponds where predators can hide (Fleury pers.obs.).As a result,birdsrequire less Crimmon 1982).The GlossyIbis and White Ibis vigilance when foraging in farm ponds, and also have expandedtheir rangesalong the Atmayexperiencelower mortality from predation lantic coast, and the White-faced Ibis has been while foraging. extending its range steadily eastwardin LouiOur data supportthe hypothesisof food limsiana.Many wading birds that breed in more itation for populationsof colonialwading birds northern regions are known to winter in Loubreedingin Louisiana,but further work is need- isianaand elsewherealong the Gulf coast(Byrd ed to establish the mechanism cause we cannot determine involved. the extent Be- 1978, Hancock and Kushlan 1984, Root 1988). to which Detailed banding studies will be required to local population increasesare due to immigra- determine what proportion of Louisiana'swintion at the regional level versus local recruit- ter populations are resident birds asopposedto ment, we cannot unambiguouslydemonstrate migrants. Emigration from neighboring states the role of food limitation in Louisianawading into Louisiana may explain some of the obbirds. served increases, but in the absence of historic Possiblealternativehypotheses.--Webriefly data and relevant data from band recoveries, considerbelow several alternative hypotheses we cannotfully evaluatethis hypothesis(Fredfor the observedtrends in populationsof Lou- erick et al. in press). Could population increasesbe due to a reisiana wading birds. These hypotheses,which leasefrom heavypesticidecontaminationin the are not mutually exclusive,include a long-term recovery from the effectsof the plume trade, 1950sand 1960s?Per-count data for all species showrelativelyflat populationcurvesfrom 1949 range expansion of wading-bird species in to 1960, followed by a general decline beginnorthernstates,recoveryfrom the effectsof DDT July1995] Crayfish Aquaculture andWading-bird Populations ning about 1960and continuing through about 1970 (Fig. 2). CBC efforts during this period generally were stableor increasing(exceptfor 1963) in number of counts, party-hours, and party-miles (Fig. 1). The timing of the declines in Louisiana wading-bird populations corresponds with similar pesticide-related declines noted for cormorants(Morrison and Slack 1977), Brown Pelicans(Pelecanus occidentalis; Schreiber and Mock 1987), and raptors (Bednarz et al. 1990).Recoverycoincideswith the banning of DDT in 1972. We conclude, therefore, that some of the population increaseswe have documented (Fig. 2) could have resulted from recoveryof populationsfollowing the banningof DDT and other pesticides.However, not all the post-1970population changesare attributable to release from pesticide effects, becausethis hypothesis predicts rangewide increases,and these are not observedin Florida and Texas(Table 3). Competition does not appear to be a major limiting factor for colonial wading-bird popu- lations,at leastat presentpopulation densities. The high positive covariance of wading-bird populationsin our study arguesagainsta strong competitive interaction among speciesof Louisiana wading birds (Schluter 1984). The birds are highly social,breeding and feeding together in large numbers,with a well-defined partitioning of resources(Burger 1978, Kushlan 1978). Predation is an important limiting factor for 627 success of many speciesin a particular year, and alsoaffectCBC countsby depressingvolunteer efforts. Severe winter weather in 1962, 1963, and 1968,for example,causedCattle Egretsto decline in both Florida and national CBC counts (Bockand Lepthien 1976,Larson1982),and 1963 winter storms reduced CBC efforts in Louisiana to a single count. Although weather fluctuations may explain at least part of the annual variation in population size, they cannot accountfor the long-termexponentialgrowth of someLouisianawading-bird populations. Habitat destructionand degradationdue to water management, urban development, impoundment, and wetland drainage, coupled with seve•ral yearsof drought,havecontributed to the precipitousdecline of wading-bird populations in southern Florida and California (Small 1975, Kushlan and White 1977, Bancroft 1989, Ogden 1994). Louisianaalso has experienceda significantlossof inland wetland habitatsduring the past40 years(R. P. Martin 1991), but an abundanceof suitable wading-bird habitat remains. Forested wetlands in Louisiana compriseabout 7,400,000ha, with an additional 8,400,000 ha of nonforested wetlands (Williams and Chabreck 1986).Louisianawading birds do not seem to be limited by the availability of suitable nesting sites, and a recent survey of wading-bird colonies in southern and coastal Louisiana found little change in the number and turnover rate of coloniesfrom the previous census (Keller et al. 1984, Martin and Lester 1990).Aquaculturepondshavenot significantly alteredthe quantityof foraginghabitat,but have sufficientlyto releasewading-birdpopulations. provided a new and higher-quality habitat in Frederickand Collopy(1989a)observedthat 43% termsof predictabilityin spaceand time, aswell of wading-birdnestlossin the Evergladeswas as high densitiesof preferred prey. Not all flooded fields provide high-quality due primarily to predation by snakesor raccoons(Procyonlotor). Both these predatorsare foraginghabitats.Crayfishpondsfrequentlyare abundant in Louisianaas well, and probably reflooded after drawdown and seeded with rice (Huner 1990, Huner and Romaire 1990). Wadaccountfor a significantproportion of nestfailing birdsfrequently foragein thesefloodedrice ure. We have seenno evidencethat thesepredatorshavedecreasedsignificantlyover the study fields (Cardiff and Sinalley 1989, Reinsen et al. 1991).Although rice fields in Italy provide critperiod. Snake populations have declined locally in areas of severely disturbed habitat, but ical foraging habitat for Black-crownedNightthere has been no noticeable change in total Herons and Little Egrets(Egrettagarzetta;Fasola populations(B. Prima pers. comm.).Crowsalso 1983, 1986), we found no significant positive correlation between any wading-bird populaprey on wading-bird nests(Frederick and Collopy 1989a).Analyses of 1949-1988 CBC data tions and changesin rice-field acreagein Lousome avian populations, but there is no evidence to suggestthat predation has decreased for FishCrows(Corvus ossifragus) andAmerican isiana (Table 4; Fielder and Nelson 1982, Uni- Crows(C. brachyrhynchos) show increasingpopulationsthat peakin 1982and declinethereafter (B. Fleury unpubl. data). Weather conditions can affect reproductive versity of New Orleans 1990). Use of a wide variety of powerful pesticidesin Louisianarice fieldsmaydepresspopulationsof fish,crayfish, and other invertebrate prey species(Louisiana 628 FLEI/R¾^Nr) SHERRY T^BLE7. Total United StatesAnimal Damage Control depredation permit kills authorized and reported in 1991(compiledby U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). Group Authorized Reported Egrets 2,766 1,174 Herons 4,300 2,400 Night-herons Cormorants Pelicans Kingfishers 175 10,814 243 6,789 50 43 216 126 Gulls 1,338 561 Coots 200 134 Anhingas Grebes Ducks Miscellaneous Total 0 19 70 110 336 20 4,665 24,704 1,483 13,328 StateUniversityAgriculturalCenter 1987).Pesticide use in French rice fields adversely af- fectedLittle Egretforaging(Hafner et al. 1986) To summarize our evidence for the hypoth- [Auk, Vol. 112 and stateand federal wildlife officialsis likely to increase (Boyd 1991). Current aquaculture farm-managementpoliciesare focusedon scaring birds from pondswith a variety of nonlethal methodssuchaspyrotechnics(butanecannons, "screamer"shotgunshells,etc.), and screening pondsto limit accessby birds. When nonlethal methodsfail to reduce bird predation, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) permits allow limited taking of wading birds (Stickley and Andrews 1989, Littauer 1990a, 1990b, Boyd 1991).Reportedbird kills in 1991 under USDA depredation permits, issuedmainly to Mississippi catfishfarmers,included 2,400heronsand 1,174egrets(Table 7), and the National Audubon Society also has documented extensive illegal killing of wading birds (Williams 1992). Avian predatorson crayfishfarmsactually may have a minimal effect on the final harvest (Hunet 1976, 1983). Martin (1979) estimated that wading birds consumedonly about 1% of the total commercial harvest, and Martin and Ham- ilton (1985) estimatedconsumptionat lessthan esisthat crayfishaquacultureis the primaryfac- 2% of the commercial harvest. Becausehigh tor causingthe dramaticincreasesin wading- crayfishdensityresultsin reducedaveragecraybird populationsin Louisiana,the highestwad- fish size, limited predation by birds actually ing-bird populationincreasesoccurredduring may benefit crayfish farmers by reducing the the 20-year period in which the crayfishin- level of intraspecificcompetition among craydustrywasexpanding.Increasedpond acreage fish. The timing and duration of crayfishfarm correlates best with the abundances of those drawdownand floodingperiodsacrossthe state, species knownto prey mostheavilyon crayfish. and their relation to the reproductive cycle of Pond drawdowns may influence population colonial wading birds need further investigagrowth by providinga predictableand readily tion, as do the effectson bird populations of available food resourceduring the incubation, farmerseliminatingaccess to aquacultureponds. nestlingand fledging periods.Finally, the al- Gooddocumentationof avianpopulationtrends, ternative hypothesesare not compelling. predationrates,andthe actualimpactof wading Conservation andmanagement implications.--Our birds on commercialcropsare needed to estabfindings have important implicationsfor the lish sound management practices.Our study conservationand managementof wading birds. representsan early step towardsthat goal. The increasesin several specieswintering in Louisiana and corresponding increases in breeding-birdpopulationssuggestthat Louisianawill continue to provide critically important habitat for wintering and breeding North American colonial wading birds. Current wet- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank JayHuner for his invaluableassistance, and Tom Bancroft, Peter Frederick, Fran James, Jim Kushlan,JohnOgden, and Allan Strongfor review- lands managementoften is aimed exclusively ing variousdraftsof thismanuscript.Our researchis at enhancingduck habitat,particularlyin na- presentlysupportedby the LouisianaCrawfishProtional wildlife refuges,and thesemanagement motion and Research Board. policiesneed to be reevaluatedfor their possibleimpacton colonialwading-birdhabitatre- LITERATUP, E CITED quirements. The strongpositivepopulationincreasesthat ARBIB,R. S., JR. 1981. The Christmas Bird Count: we have documented in many Louisiana pop- Constructingan "ideal model."Stud.Avian Biol. ulationsof colonialwading birds alsoindicate that the conflict between aquaculturefarmers 6:30-33. BANCROFT,G. T. 1989. Status and conservation of July1995] Crayfish Aquaculture andWading-bird Populations wading birds in the Everglades.Am. Birds 43: 1258-1265. BANCROFr,G. T., J. C. OGDEN,AND B. W. PATTY. 1988. Wadingbird colonyformationand turnoverrelative to rainfall in the CorkscrewSwampareaof Florida during 1982 through 1985. Wilson Bull. 100:50-59. BANCROFr,G. T., A.M. STRONG,R. J. S^wIcICI, W. HOFFMAN, ANDS.D. JEWELL. 1994. Relationships amongwading bird foragingpatterns,colonylocations,and hydrology in the Everglades.Pages 615-657 in Everglades:The ecosystemand its restoration(S.M. Davis,J.C. Ogden,and W. A. Park, Eds.).St. Lucie Press,Delray Beach,Florida. B^¾NARD, O. E. 1913. Home life of the GlossyIbis (Plegadis automnolis). Wilson Bull. 25:103-117. B•.•L, K. G., AND H. J. KHAMIS. 1990. Statisticalanal- ysis of a problem data set: Correlated observations. Condor 92:248-251. E. SENNER.1990. Migration countsof raptorsat Hawk Mountain, Pennsylvania,as indicatorsof population trends, 1934-1986.Auk 107:96-109. BENT, A. C. 1926. Life histories of North American marsh birds. U.S. Natl. Mus. Bull. 135. BILDSTmN, K.L. 1983. Age-relateddifferencesin the flockingand foragingbehavior of White Ibises in a South Carolina salt marsh. Colon. Waterbirds 6:45-53. BILDSTEIN,K.L. 1993. White Ibis: Wetland wanderer. SmithsonianInstitution,WashingtonD.C. BILDSTEIN,K. L., W. Post, J. JOHNSTON,AND P. FREDFaUCet.1990. Freshwater wetlands, rainfall, and the breeding ecologyof White Ibisesin coastal South Carolina. Wilson Bull. 102:84-98. BLADES,H. C., JR. 1974. The distribution of south Louisianacrayfish.Pages621-628in Papersfrom the SecondInternational Symposiumon Freshwater Crayfish(J. A. Avault, Jr., Ed.). Louisiana ibises. Condor 80:15-23. BUTCHER,G.S. 1990. Audubon Christmas Bird Counts. Pages5-13 in Surveydesignand statisticalmethodsfor the estimationof arian populationtrends (J. R. Sauer and S. Droege, Eds.). U.S. Fish and Wildl. Serv. Biol. Rep. 90(1):5-13. BUTCHER,G. S., M. R. FULLER,L. S. MCALLISTER,AND P. H. GmssLER. 1990. An evaluation of the ChristmasBirdCountfor monitoringpopulation trends of selectedspecies.Wildl. Soc. Bull. 18: 129-134. BYRD,M. A. 1978. Dispersaland movementsof six North American ciconiiforms.Pages161-185 in Wading birds (A. Sprunt IV, J. Ogden, and S. Winckler, Eds.).National Audubon SocietyResearchReportNo. 7. National AudubonSociety, York. BYstP, AIC,D. 1981. The North American Breeding Bird Survey. Stud. Avian Biol. 6:34-41. CARDIFF,S. W., AND G. B. SMALLEY. 1989. Birds in the rice countryof southwestLouisiana.Birding 21:232-240. CEZILLY, F. 1992. Turbidity asan ecologicalsolution to reducethe impactof fish-eatingcolonialwaterbirds on fish farms. Colon. Waterbirds 15:249- 252. CEZ•LLY, F., ANDV. BOY. 1988. Age related differencesin foragingLittle Egrets(Egrettagarzetta). Colon. Waterbirds 11:100-106. CONFER,J. L., T. KXARET,AND L. JONES.1979. Effort, locationand the ChristmasBird Count tally. Am. Birds 33:690-692. CONN•FF, R. 1991. Why catfishfarmerswant to throttie the crow of the sea.Smithsonian22(4):44-55. DRAULANS, D. 1987a. The effectof prey density on foragingbehaviourand success of adult and firstyear Grey Herons (Ardeacinerea).J. Anita. Ecol. 56:479-493. State Univ., Baton Rouge. BOCK,C. E., ANDL. W. LEPTI-nEN. 1976. Population growth in the Cattle Egret. Auk 93:164-166. Boot, C. E., AND T. L. Root. BURGER, J. 1978. CompetitionbetweenCattleEgrets and native North American herons, egrets,and New BEVNARZ,J. C., D. KLEM,JR., L. J. Goov•acI-I, ANY S. 629 1981. The Christmas Bird Countand avian ecology.Stud.Avian Biol. DRAULANS, D. 1987b. The effectiveness of attempts to reduce predation by fish-eating birds: A review. Biol. Conserv. DP,F,NNAN, S.R. 41:219-232. 1981. The Christmas Bird Count: An 6:17-23. overlookedand underusedsample.Stud. Avian Biol. 6:24-29. BOYD,F. L. 1991. Bird/aquaculturemanagement conflicts.Pages153-155 in ProceedingsCoastal DUNN, E. H. 1986. Feeder counts and winter bird population trends.Am. Birds 40:61-66. NongameWorkshop(D. P. Jennings,Comp.).U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. ERWIN,R. M. 1983. Feedingbehavior and ecology BRAY,M.P., AND D. A. KLESENOW.1988. Feeding of colonialwaterbirds:A synthesisand concludecology of White-faced Ibises in a Great Basin ing comments.Colon. Waterbirds6:73-82. F^L•C, L. L. 1979. An examination of observers' valley, U.S.A. Colon. Waterbirds11:24-31. BUCI-IHmSTER, C. W., AND F. GRAHAM,JR. 1973. From weathersensitivityin ChristmasBirdCount data. Am. Birds 33:688-689. the swampsand back:A conciseand candid history of the Audubon movement.Audubon 75(1): F^soLA,M. 1983. Nestingpopulationsof heronsin 7-45. Italy dependingon feedinghabits.Boll.Zool. 50: BURDICK,D. M., D. CUSHMAN,R. HAMILTON, AND J. G. GOSSELINIC. 1989. Faunal changesand bottomland hardwood forest loss in the Tensas Water- shed, Louisiana. Conserv. Biol. 3:282-292. 21-24. FASOLA, M. 1986. Resourceuse of foraging herons in agriculturaland nonagriculturalhabitatsin Italy. Colon. Waterbirds9:139-148. 630 FLEURY ANDSHERRY FERNER,J. W. 1984. The Audubon Christmas Bird Countasa methodof monitoringnongamebird populations.Pages332-341in Proceedings Workshopon Managementof NongameSpeciesand [Auk,Vol. 112 Little Egrets(Egrettagarzetta)in the Camarge, southern France. Colon. Waterbirds 9:149-154. HANCOCK,J., AND J. KUSHLAN. 1984. The herons handbook. Croom Helm, London. Ecological Communities (W. C. McComb, Ed.). HOLMES, R. T., ANDT. W. SHERRY.1988. Assessing Univ. Kentucky,Lexington. populationtrendsof New Hampshireforestbirds: FIELDER, L., ANDB. NELSON.1982. Agricultural staLocal vs. regional patterns.Auk 105:756-768. tisticsand pricesfor Louisiana1924-1981.Loui- HOLMES,R. T., T. W. SHERRY,AND F. W. STURGES.1986. sianaStateUniv. Dept. Agricultural Economics Bird communitydynamicsin a temperatedecidand Agribusiness, DAE ResearchReportNo. 600. uousforest:Long-term trends at Hubbard Brook. LouisianaStateUniv., BatonRouge. Ecol. Monogr. 56:201-220. FREDERICK, P. C., K. BILDSTEIN, B. FLEURY,AND J. OGDrY. In press. Conservingmoving targets:White Ibis (Eudocimus albus)population shifts in the United States. Conserv. Biol. FREDERICK,P. C., AND M. W. COLLOPY. 1989a. The role of predation in determining reproductive success of coloniallynestingwading birdsin the Florida Everglades.Condor 91:860-867. FREDEPaCK,P. C., AND M. W. COLLOPY. 1989b. Nest- ing success of five ciconiiformspeciesin relation to water conditionsin the Florida Everglades. Auk 106:625-634. FREDERICK,P. C., AND M. G. SPALDING. 1994. Factors HOWELL, A. H. 1932. Florida bird life. Florida De- partment of Fish and Game, Tallahassee. HUNER,J. V. 1983. Observationson wading bird activity.CrawfishTales2(3):16-19. HUNER,J.V. 1990. Biology,fisheries,and cultivation of freshwater crawfishesin the U.S. Aquat. Sci. 2:229-254. HUNER,J. V. 1994. Cultivation of freshwatercrayfishesin North America. Pages5-156 in Freshwatercrayfishaquaculture in North America,Europe, and Australia. Families Astacidae,Cambaridae, and Parastacidae(J. V. Huner, Ed.). Haworth Press,Binghamton,New York. HUNER, J. V., AND R. P. ROMmRE. 1990. Crawfish affectingreproductivesuccessof wading birds culture in the southeasternUSA. World Aqua(Ciconiiformes)in the Evergladesecosystem. cult. 21:58-65. Pages659-691in Everglades: The ecosystem and JENNI, D.A. 1969. A study of the ecologyof four its restoration(S. M. Davis,J. C. Ogden,and W. species of herons during the breeding seasonat A. Park,Eds.).St.LuciePress,DelrayBeach,FlorLakeAlice, AlachuaCounty,Florida.Ecol.Monida. FROHRING, P. C., D. P. VOORHEES, ANDJ. A. KUSHLAN. 1988. History of wading bird populationsin the Florida Everglades:A lessonin the use of historical information. Colon. Waterbirds 11:328-335. ogr. 39:245-270. JENNI,D.A. 1973. Regionalvariation in the food of nestlingCattle Egrets.Auk 90:821-826. KAHL,M.P., JR. 1963. Mortality of CommonEgrets and other herons. Auk 80:295-300. GARY,D. L. 1974a. The geographyof commercial KELLER,C. E.,J. A. SPENDELOW, AND R. D. GRF. ER. 1984. crayfishpondsin South Louisiana.Pages117Atlasof wadingbird andseabirdnestingcolonies 124 in Papers From the Second International Symposium on FreshwaterCrayfish(J.A. Avault, Jr., Ed.). LouisianaStateUniv., BatonRouge. GARY, D.L. 1974b. The commercial crawfish indus- try of southLouisiana.LouisianaStateUniversity Center for WetlandsResources, BatonRouge. GEISSLER, P. H. 1984. Estimationof animal population trendsand annualindicesfrom a surveyof call-counts or other indicators. Proc. Am. Stat. Assn.,Sectionon SurveyResearch Methods1984: 472-477. GEISSLER,P. H., AND B. N. NOON. 1981. Estimates of in coastalLouisiana,Mississippi,and Alabama: 1983. FWS/OBS-84/13. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service,WashingtonD.C. KUSHLAN,J.A. 1976. Wading bird predation in a seasonallyfluctuating pond. Auk 93:464-476. KUSHLAN,J. A. 1978. Feeding ecology of wading birds. Pages249-297 in Wading birds (A. Sprunt IV, J. Ogden, and S. Winckler, Eds.). Nationa• AudubonSocietyResearchReportNo. 7. National Audubon Society,New York. KUSHLAN, J.A. 1979. Feeding ecologyand prey selection in the White Ibis. Condor 81:376-389. avian population trends from the North Ameri- KUSHLAN,J.A. 1986. Responsesof wading birds to canBreedingBird Survey.Stud.Avian Biol.6:42- seasonally fluctuatingwater levels:Strategies and 51. GEISSLER, P. H., AND J. R. SAUER.1990. Topics in route-regression analysis.Pages54-57 in Survey design and statisticalmethods for the estimation of avian population trends (J. R. Sauer and S. Droege, Eds.). U.S. Fish and Wildl. Serv. Biol. Rep. 90(1). HAFNER,H., P. J. DUGAN,AND V. BOY. 1986. Use of artificialandnaturalwetlandsasfeedingsitesby their limits. Colon. Waterbirds 9:155-162. KUSHLAN,J. A., AND M. S. KUSHLAN. 1975. Food of the White Ibis in southern Florida. Fla. Field Nat. 3:31-38. KUSHLAN,J. A., J. C. OGDEN,AND A. L. HIGER. 1975. Relationof water level and fish availability to Wood Stork reproductionin the southernEverglades,Florida.U.S.GeologicalSurvey,OpenFile Report 75-434. July1995] Crayfish Aquaculture andWading-bird Populations KUSHLAN,J. A., AND D. A. WHITE. 1977. Nesting wading bird populationsin southernFlorida. Fla. Sci. 40:65-72. techniquesfor reducing bird damageat aquaculturefacilities.SouthernRegionalAquaculture Center, SRAC Publication No. 401. LITTAUER, G. A. 1990b. Control of bird predation at aquaculture facilities: Strategiesand cost estimates. Southern Regional Aquaculture Center, SRAC Publication LOUISIANA No. 402. STATE UNIVERSITY AGRICULTURAL CENTER. 1987. Riceproductionhandbook.LouisianaState Univ. Agricultural Center, Baton Rouge. MCCRIMMON, D.A. 1982. Populationsof the Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias)in New York State from 1964 to 1981. Colon. Waterbirds 5:87-95. McSHmm¾,J. M. 1982. Crawfish from pond to pot. La. Conservationist 34(2):4-9. MADDOCK,M., AND G. S. BAXTER.1991. Breeding successof egrets related to rainfall: A six-year Australian study. Colon. Waterbirds 14:133-139. MARTIN,R.P. 1979. Ecologyof foragingwadingbirds at crayfishponds and the impact of bird predation on commercialcrayfishharvest.M.S. thesis, Louisiana State Univ., Baton Rouge. MARTIN,R. P. 1991. Regional overview of wading birdsin Louisiana,MississippiandAlabama.Pages 22-33 in Proceedings Coastal Nongame Workshop(D. P. Jennings,Comp.).U.S. Fishand Wildlife Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. MARTIN,R. P., AND R. B. HAMILTON. 1985. Wading bird predationin crawfishponds.La.Agric. 28(4): 3-5. MARTIN, R. P., AND G. D. LESTER. 1990. Atlas and censusof wading bird and seabird nesting colonies in Louisiana:1990. Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries,BatonRouge.Louisiana Natural Heritage Program, Special Publication No. 3. MARTIN,T.E. 1987. Foodasa limit on breedingbirds: A life-history perspective.Annu. Rev. Ecol.Syst. 18:453-487. MARTIN, T. E. 1991. Food limitation in terrestrial breeding bird populations:Is that all there is? Pages 1595-1602 in Acta XX CongressusInternationalis Ornithologici. Christchurch, New Zealand, 1990. New Zealand Ornithol. Congr. Trust Board,Wellington. MOCK, D. W., T. C. LAMEY,AND B. J. PLOGER. 1987. Proximate and ultimate roles of food amount in regulating egret sibling aggression.Ecology 68: 1760-1772. and status of the Olivaceous Cormorant. Am. Birds 31:954-959. NEWTON,I. 1980. The role of food in limiting bird numbers. summer food habits of three heron speciesin Louisiana. Colon. Waterbirds 6:148- 153. OGDEN,J. C. 1978. Recent population trends of colonial wading birds on the Atlantic and Gulf coastalplains.Pages137-153 in Wading birds (A. Sprunt IV, J. Ogden, and S. Winckler, Eds.). National Audubon SocietyResearchReport No. 7. National Audubon Society,New York. OGDEN,J. C. 1991. Wading bird regional overview for Florida. Pages 18-21 in Proceedingsof the Coastal Nongame Workshop (D. P. Jennings, Compiler). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. OGDEN,J. C. 1994. A comparisonof wading bird nesting colony dynamics(1931-1946 and 19741989)asan indicationof ecosystemconditionsin the southern Everglades.Pages 533-570 in Everglades:The ecosystem and its restoration(S. M. Davis, J.C. Ogden, and W. A. Park, Eds.).St. Lucie Press,Delray Beach,Florida. PALMER, R. S. 1962. Handbook of North American birds.Vol. 1, Loonsthroughflamingos.Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, Connecticut. PARNELL,J. F., D. G. AINLEY,H. BLOKPOEL, B. CAIN, T. W. CUSTER,J. L. DUSI, S. KRESS,J. A. KUSHLAN,W. E. SOUTHERN,L. E. STENZEL,AND B.C. THOMPSON. 1988. Colonial waterbird managementin North America. Colon. Waterbirds 11:129-169. PORTNOY, J. W. 1977. Nesting coloniesof seabirds and wading birds--CoastalLouisiana,Mississippi, and Alabama. US F&WS OBS-77/07. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service,Washington,D.C. PORTNOY, J. W. 1978. A wading bird inventory of coastalLouisiana.Pages227-234 in Wading birds (A. Sprunt IV, J. Ogden, and S. Winckler, Eds.). National Audubon Society ResearchReport No. 7. National Audubon Society,New York. POWELL, G. V.N. 1983. Foodavailability and reproduction by Great White Herons, Ardea herodias: A food addition study. Colon. Waterbirds 6:139147. POWELL, G. V. N., R. D. BJORK, J. C. OGDEN,R. T. PAUL, A. H. POWELL,AND W. B. ROnERTSON, JR. 1989. Population trends in some Florida Bay wading birds. Wilson Bull. 101:436-457. RAYNOR, G.S. 1975. Techniquesfor evaluatingand analyzing ChristmasBird Count data. Am. Birds 29:626-633. RECH•, H. F., ANDJ. A. I•CHER. 1969. Comparative foraging efficiencyof adult and immature Little Blue Herons (Florida caerulea).Anim. Behav. 17: 320-322. RECH•, H. F., ANDJ.A. RECH•. 1980. Why are there MORRISON, M. L., ANDR. D. SLACK.1977. Population trends NIETHAMMER, K. R., AND M. S. KAISER. 1983. Late northeastern LAI•ON, S.E. 1982. Winter population trends in the Cattle Egret. Am. Birds 36:354-357. LITTAUER, G.A. 1990a. Avian predators:Frightening 631 Ardea 68:11-30. different kinds of herons? N.Y. Linn. Soc. Trans. 10:135-158. REMSEN,J. V., M. M. SWAN,S. W. CARDIFF,AND K. V. ROSENBERG. 1991. The importance of the ricegrowing region of south-central Louisiana to 632 FI.EUI•¾ ANDSHERRY winter populationsof shorebirds,raptors,wad- ers, and other birds. J. La. Ornithol. 1:34-47. RIEGNER,M. F. 1982. The diet of Yellow-crowned Night Heronsin the easternandsouthernUnited States. Colon. Waterbirds 5:173-176. ROBBINS,C. S., AND D. BYSTRAK. 1974. The winter bird surveyof central Maryland, USA. Acta Ornithol. 14:254-271. ROBERTSON, W. B., AND J. A. KUSHLAN. 1974. The southern Florida avifauna. Miami Geol. Soc. Mem. 2:414-452. SMALL, A. 1975. The birds of California. Winchester, New York. SMITH,K.G. 1979. The effectof weather,people,and time on 12 Christmas Bird Counts, 1954-1973. Am. Birds 33:698-702. SNEATH, P. H. A., • Herons Florida caerulea on the west coast of Florida. Fla. Field Nat. 10:25-30. RODGERS, J. A., JR.,ANDS. A. NESBITT.1979. Feeding energeticsof heronsand ibisesat breedingcolonies.Pages128-132in Proceedings ColonialWaterbird Group(W. E.Southern,Compiler).Northern Illinois Univ., DeKalb. ROLLFIN'ICE, B. F., AND R. H. YAHNER. 1990. Effects of time of day and seasonon winter bird counts. 92:215-219. ROOT,T. 1988. Atlas of wintering North American birds:An analysisof ChristmasBird CountData. Univ. ChicagoPress,Chicago. RYDER,R. A. 1978. Breeding distribution, movements,and mortality of Snowy Egretsin North America. Pages 197-205 in Wading birds (A. Sprunt IV, J. Ogden, and S. Winckler, Eds.).National Audubon SocietyResearchReport No. 7. National Audubon Society,New York. SCH•,UTER, D. 1984. A variancetestfor detecting species associations,with some example applications. Ecology65:998-1005. SCHREIBER, R. W., AND P. J. MOCK. 1987. Christmas Bird Counts as indices of the population status of Brown Pelicansand three gull speciesin Florida. Am. Birds 41:1334-1339. R. R. SOKAL. 1973. Numerical taxonomy. W. H. Freeman, San Francisco. SPRUNT,A., JR.,AND E. B. CHAMBERLAIN.1949. South Carolina bird life. Univ. South Carolina Press, Columbia. STEWART,P.A. RODGERS, J.A., JR. 1982. Foodof nestlingLittle Blue Condor [Auk,Vol. 112 Counts. 1954. The value of the Christmas Bird Wilson Bull. 66:184-195. STICKLœ¾, A. R., ANDK. J. ANDREWS.1989. Surveyof Mississippicatfishfarmerson means,effort, and coststo repel fish-eatingbirdsfrom ponds.Pages 105-108 in Proceedingsof the EasternWildlife DamageControl Conference(4th, 1989).Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources,Madison. STICKLEY,A. R., JR., G. L. WmmIOC, AND J. F. G•S.HSr. 1992. Impact of Double-crestedCormorant depredations on channel catfish farms. J. World Aquacult. Soc. 23:192-198. T•FAIR, R. C. II. 1981. Cattle Egrets,inland heronties, and the availability of crayfish.Southwest. Nat. 26:37-41. UNIVERSITY OF NEW OR•,EA•S. 1990. Statistical ab- stract of Louisiana, 8th ed. University of New Orleans Division of Business and Economic Re- search. Univ. New Orleans, New Orleans. Wml,mMS,T. 1992. Killer fish farms. Audubon 94(2): 14-22. Wmt,i•as, S. O., III, AND R. H. CHABRECK. 1986. Quantity and quality of waterfowl habitatin Louisiana.Schoolof Forestry,Wildlife, and Fisheries, ResearchReportNo. 8. LouisianaStateUniv., Baton Rouge.