2 - Saica

advertisement

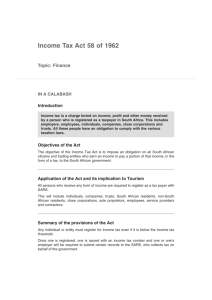

MARCH 2015 – ISSUE 186 CONTENTS COMPANIES TAX ADMINISTRATION ACT 2392. Interest-free shareholder loans 2398. Mitigation of penalties and 2393. Asset for share transactions interest 2394. Section 9D rules DEDUCTIONS TRANSFER PRICING 2395. Thin capitalisation and section 2399. Compliance conundrum 23M 2396. 2400. OECD’s BEPS action plan Penalties and stolen money INTERNATIONAL TAX SARS NEWS 2397. Dividend payments to Holland 2401. Interpretation notes, media releases and other documents COMPANIES 2392. Interest-free shareholder loans Loans between companies and their shareholders, or other group companies, are a common method of providing finance in the South African corporate environment. Loans of this nature may, however, give rise to tax implications in the hands of the lender or the recipient, and careful consideration should therefore be given to these transactions. Dividends tax 1 Dividends declared by a company to its shareholders up until 31 March 2012 were subject to Secondary Tax on Companies (STC) at a rate of 10%. The Income Tax Act, No. 58 of 1962 (the Act) also contains provisions designed to circumvent tax avoidance transactions that enabled the shareholder of a company to benefit in some way even though no cash dividend was actually declared. Under these provisions, certain types of transactions gave rise to deemed dividends with the result that STC became payable, subject to certain exemptions. Dividends tax is levied at the rate of 15% on dividends paid on or after 1 April 2012, subject to certain exemptions, or the application of a lower rate of dividends tax in certain circumstances. Low-interest loans may also fall within the dividends tax ambit by virtue of these loans constituting a deemed dividend in certain circumstances, giving rise to a liability for dividends tax. Loans or advances from a company to a shareholder (or any person connected to the shareholders) will automatically be deemed to be dividends in certain circumstances. The current deemed dividend provision applies where a debt arises “by virtue of a share held in the company” and where the following conditions are present: the debtor is a person other than a company; the debtor is a South African resident and the debtor is either a connected person in relation to the company, or a connected person in relation to that person. Broadly speaking, a “connected person” in relation to a company means any company that forms part of the same group of companies (where at least 70% of the equity shares in a controlled group company are held by the controlling group company), or any person, other than a company, who individually or jointly with any connected person holds, directly or indirectly, at least 20% of the company’s equity shares or voting rights. If all of these requirements are met, the company is deemed to have paid a dividend in specie which is deemed to be an amount equal to the greater of the “market related interest” in respect of the debt, less the amount of interest payable 2 to that company in respect of the relevant year of assessment. In other words, the amount of the dividend is determined by applying an interest rate to the debit balance on the loan during the year. For purposes of determining the deemed dividend, the term “market related interest” is the difference between the “official rate of interest” that applies for fringe benefits tax purposes, and as defined in paragraph 1 of the Seventh Schedule (currently 6.75% per annum), and the actual interest rate charged on the loan. Only the interest effectively forgone, and not the capital amount of the loan, is deemed to be a dividend. If therefore, the loan bears interest at an acceptable rate, there would be no deemed dividend. This can be distinguished from the STC regime where the tax in respect of a deemed dividend was calculated on the principal amount of the loan. The dividend is deemed to be paid by the company on the last day of the year of assessment, and the company is required to pay the resulting dividends tax by the end of the month following its year-end. Since the dividend is deemed to be a dividend in specie, the company (as opposed to the shareholder) is liable for the tax. In order for a shareholder loan to constitute a deemed dividend, the debt has to arise “by virtue of” a share held in the company. The meaning of the phrase “by virtue of” is not defined in the Act and guidance can be found in a number of cases. The phrase “by virtue of” was considered in the context of employment, in the case of Stander v CIR [1997] 59 SATC 212, where the court considered the meaning of the phrase “in respect of or by virtue of any employment or the holding of any office”. The words “by virtue of” do not, in view of the court, bear a meaning materially different from the words “in respect of” and referred to ST v Commissioner of Taxes [1973] 35 SATC 99, at 100 where, in regard to the phrase “by virtue of” Whitaker P stated at 100: 3 “ordinarily the phrase (and this was common cause between counsel) means ‘by force of’, ‘by authority of’, ‘by reason of’, ‘because of’, ‘through’ or ‘in pursuance of’. (See Black’s Law Dictionary 4 ed 252). Each of these definitions suggests there must be a direct link between the cause and result.” The principles established in the Stander case were confirmed in the Supreme Court of Appeal case of Stevens v CIR [2007] 69 SATC 1, where the court held that there was no material difference between the expressions “in respect of” and “by virtue of”. They connote a causal relationship between the amount received and the taxpayer’s services or employment. It is evident from the above that there has to be a direct causal relationship between the holding of the relevant shares and the advance of the loan in question in order for a deemed dividend to arise. The deeming rule will thus only be triggered when a loan or advance has been made to a South African resident person that is not a company (e.g. a trust or a natural person) who is a connected person in relation to that company or a connected person in relation to the aforementioned person (that is connected to the person who is connected to the company). To the extent that the amount owing to a company by a shareholder of that company or other qualifying person, as set out above, was deemed to be a dividend that was “subject to STC”, no deemed dividend implications will arise in terms of the dividends tax regime. In other words, a debt that was deemed to be a dividend that was subject to STC will not be deemed to be a dividend for dividends tax purposes. The term “subject to tax” is not defined in the Act, nor has it been the subject of any South African court decisions. Guidance can, however, be found from United Kingdom (UK) judgments in respect of the phrase. In the case of Paul Weiser v HM Revenue and Customs [2012] UKFTT 501, the First Tier Tribunal considered 4 the interpretation of the double tax treaty between the UK and Israel and in particular the meaning of the phrase "subject to tax". The case centred around the meaning of the phrase "subject to tax" and the difference in international tax treaties between this phrase and the phrase "liable to tax". In HM Revenue and Custom's view, the distinction between the two phrases is that the expression "liable to tax" requires only an abstract liability to tax (i.e. a person is within the scope of tax generally irrespective of whether the country actually exercises the right to tax) and therefore has a much broader meaning than the phrase "subject to tax" which requires that tax is actually levied on the income. The First Tier Tribunal decided the case in favour of HM Revenue and Customs such that relief was not available under the UK-Israel tax treaty to exempt the pension from UK tax because the pension in question was not subjected to tax in Israel. Income would thus not be regarded as “subject to tax” if the income in question is exempt from tax in terms of a statutory exemption from tax. In the context of shareholder’s loans, unless STC was actually paid in respect of the debt in question, such interest-free or low interest loan would be subject to dividends tax. This effect appears to create unintended adverse consequences for taxpayers in that, even though loans of this nature may not have constituted deemed dividends under the STC regime as a result of the application of an exemption, excess interest on the loan amount would be subject to dividends tax. Employees’ tax For employees’ tax purposes, the issue that requires consideration is whether a “taxable benefit” as defined in paragraph 2(f) of the Seventh Schedule to the Act, read with paragraph 11 thereof, arises in consequence of an interest-free or low interest loan to a shareholder that is a connected person in relation to the lender. In order to constitute a “taxable benefit”, the debt in question has to arise “in respect of” the employee’s employment with the employer. As discussed above, in terms of the applicable case law, there is no material difference between the 5 expressions “in respect of” and “by virtue of”. With regard to both, if there is an “unbroken causal relationship between the employment on the one hand and the receipt on the other”, the payment will be “in respect of services rendered” (Stevens v CSARS supra). It is submitted that the same principle will apply for purposes of paragraph 2 of the Seventh Schedule to the Act. In order to determine whether an interest-free or low interest loan results in a taxable benefit, one will have to determine the reason or cause for the granting of the loan. It is important to bear in mind that an interest-free or low interest loan to a connected person in relation to the company (or a connected person in relation to a connected person in relation to the company) will only be subject to either dividends tax or employees’ tax, and not to both. ENSafrica ITA: Sections 64B, 64E and Seventh Schedule’s paragraphs 1, 2 and 11 2393. Asset for share transactions (Editorial note: Published SARS rulings are necessarily redacted summaries of the facts and circumstances. Consequently, they (and articles discussing them) should be treated with care and not simply relied on as they appear.) The South African Revenue Service (SARS) released Binding Private Ruling No 184 (BPR) on 11 November 2014, which deals with a proposed asset-for-share transaction in terms of section 42 of the Income Tax Act No. 58 of 1962 (the Act). 6 The applicant was a resident family trust. The trust held all the issued shares in Company A and Company B. It was proposed that the applicant dispose of its shares in Company A to Company B so that Company A could become a whollyowned subsidiary of Company B. It was further proposed that, as consideration for the transfer of the shares in Company A to Company B, Company B would issue an additional equity share to the applicant. The issue of the equity share to the trust would solely be to bring the proposed transaction within the ambit of section 42 of the Act. Despite the apparent artificiality of issuing an additional equity share to the applicant, which already held all the issued shares in Company B, SARS ruled that the proposed transaction would fall within section 42 of the Act. Section 24BA of the Act is an anti-avoidance provision that potentially applies to transactions where assets are acquired in exchange for the issue of shares as consideration, including asset-for-share transactions in terms of section 42 of the Act. Section 24BA will apply where the consideration is different from the consideration that would have applied if the transaction were between independent persons dealing at arm’s length. Where the consideration is not arm’s length, the application of section 24BA will result in either a deemed capital gain for the issuing company, or a deemed dividend in specie paid by the issuing company. SARS ruled that section 24BA would not apply to the proposed transaction on the basis that it fell within the exclusion provided for in section 24BA(4)(a)(ii). The said section provides that section 24BA does not apply where the transferor of the asset will hold all the shares issued by the issuing company immediately after the acquisition of the asset by that company. 7 SARS also ruled that the transfer of the shares in Company A (the assets) and the issue of the equity share to the applicant, would neither constitute a donation for purposes of section 54 of the Act, nor a deemed donation for purposes of section 58 of the Act (where there is inadequate consideration in respect of the disposal of property), and that accordingly the proposed transaction would not have any donations tax consequences. Further, SARS ruled that Paragraph 38 of the Eighth Schedule to the Act would not apply, implying that the proposed transaction would not be seen as a disposal of an asset to a connected person for a consideration not reflecting an arm’s length price. This ruling is interesting in that, on the face of it, the issue of the additional equity share to the applicant as consideration for the transfer of the shares in Company A to Company B, does not appear to constitute: an arm’s length consideration for purposes of section 24BA and Paragraph 38 of the Eighth Schedule to the Act; and adequate consideration for purposes of section 58 of the Act. SARS nevertheless ruled that these provisions would not apply. Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr Binding Private Ruling No 184 ITA: Section 24BA, 42, 54, 58 and Paragraph 38 of the Eighth Schedule 2394. Section 9D rules The Controlled Foreign Company (CFC) provisions seek to reduce the opportunity for income to be diverted and taxed offshore in the hands of foreign companies where: 8 South African tax residents may exercise, directly or indirectly, a majority of the voting rights in the foreign companies or where South African tax residents may participate, directly or indirectly, in the majority of the benefits attached to shares of the foreign companies. In terms of Section 9D of the Income Tax Act, No. 58 of 1962 (the Act) a hypothetical taxable income, “net income”, is calculated as if the CFC is a South African tax resident. This net income may be included in the taxable income of the South African tax resident shareholders. Section 9D offers the following relief measures that avoid subjecting the CFC’s net income to South African income tax: the net income of the CFC is deemed nil where all foreign tax incurred by the CFC is at least equal to 75% of the South African income tax computed on that net income amounts, other than tainted income, that are attributable to a “foreign business establishment” (FBE) are excluded from net income. Where a CFC conducts a genuine business established at premises outside of South Africa, with sufficient on-site managerial and operational staff, it is usually evident that the CFC conducts business through a FBE. In contrast, determining whether foreign taxes incurred by the CFC will reach the 75% threshold can be a time consuming and complicated computation, especially if the South African taxpayer has numerous CFCs. If a FBE exists and no tainted income is attributable to that FBE, no net income will need to be included in the taxable income of the South African resident shareholder. This result is regardless of whether foreign taxes incurred by the CFC meet the 75% threshold. 9 However, as noted in the Explanatory Memorandum to the 2014 Taxation Laws Amendment Act of 2014 (the TLAA), the current structure of section 9D still requires the 75% threshold computation to be performed despite the fact that the net income of the CFC is attributable to a FBE. This computation would also need to be declared in an IT10B return that accompanies the annual tax return of the South African shareholder. In recognising this unnecessary burden, the TLAA proposes that a CFC’s net income will also be deemed nil where: all of the receipts and accruals of the CFC are attributable to a FBE and none of those receipts or accruals relate to tainted income This logical amendment removes the compliance burden where CFCs conduct business through a FBE that does not derive tainted income. A word of caution – the tainted income provisions of section 9D(9A) are complicated and therefore should be considered carefully before relying on this FBE relief. Tainted income includes the following passive and diversionary income earned by CFCs from South African tax resident connected persons: interest royalties in respect of the use of intellectual property rental of certain movable property goods sold by the CFC services performed by the CFC, other than certain services performed outside of South Africa In conclusion, now that the amendments in the 2014 TLAB have been enacted by way of the Taxation Laws Amendment Act No.43 of 2014, the presence of an FBE can reduce the compliance burdens associated with a CFC. However, careful 10 consideration must still be given to establish the existence and the impact of tainted income. Grant Thornton ITA: Section 9D Taxation Laws Amendment Act No. 43 of 2014 DEDUCTIONS 2395. Thin capitalisation and section 23M In line with recent pronouncements by the OECD relating to the so-called Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project (BEPS), section 23M was introduced by the Taxation Laws Amendment Act No.31 of 2013 (the TLAA). Section 23M of the Income Tax Act No. 58 of 1962 (the Act) took effect on 1 January 2015 and has a similar purpose to the thin capitalisation provisions of section 31 of the Act. The Taxation Laws Amendment Bill No.13 Act of 2014 (TLAB), as tabled in parliament contains a number of substantial amendments to the current provisions of section 23M. The TLAB was subsequently enacted as the Taxation Laws Amendment Act, No. 43 of 2014. A summary of the provisions of section 23M following these amendments is set out below. Section 23M sets an interest deduction limitation for a debtor and will apply if a “controlling relationship” exists between the debtor and the creditor. A controlling relationship will exist where a person directly or indirectly holds at least 50 per cent of the equity shares or voting rights in a company. The interest deduction limitation will also apply in respect of a debt owed to a creditor that is not in a controlling relationship with the debtor where the creditor obtained the funding for the debt advanced from a person that is in a controlling relationship with the debtor. The interest deduction limitation will, however, only apply if the 11 amount of interest is not subject to tax in the hands of the recipient or not included in the net income of a controlled foreign company and also not disallowed under the provisions of section 23N dealing with the limitation of interest deductions in respect of reorganisation and acquisition transactions. The interest deduction limitation will be calculated on the aggregate of: • the amount of interest received by or accrued to the debtor; and • a percentage of the adjusted taxable income of the debtor to be determined in accordance with a formula which links deductible interest to the average repo rate for the year. The formula will, therefore, be adjusted where there is a change to the average repo rate together with a 400 basis point addition to the average repo rate. The interest deduction limitation will have a ceiling of 60 per cent of the adjusted taxable income of the debtor which will exclude the previous year’s assessed loss. Any interest in excess of the limitation may be carried forward to the following year. The interest deduction limitation will not apply to any interest incurred by a debtor in relation to back-to-back loans where the creditor obtained those funds from an unconnected lending institution in relation to the debtor and the interest is determined with reference to a rate that does not exceed the official rate of interest as defined in the Seventh Schedule plus 100 basis points. National Treasury and SARS are of the opinion that section 23M has a broader objective than the thin capitalisation provisions of section 31 and that section 31 will first apply to determine the correct pricing of the debt owed. Where the amount of interest is taken into account in terms of a reorganisation and acquisition transaction under section 23N, the provisions of section 23M must be applied to any amount not already disallowed under section 23N. ENSafrica ITA: Sections 23M, 23N and 31 12 Taxation Laws Amendment Act No. 31 of 2013 The Taxation Laws Amendment Act No. 43 of 2014 2396. Penalties and stolen money The South African Revenue Service (SARS) released Interpretation Note 80 on 5 November 2014 which deals with the income tax treatment of stolen money. Apart from the fact that it is indicated in the Interpretation Note that stolen monies must be included in gross income in the year of receipt, it is indicated further that the stealing of money cannot be described as a trade and that the thief will thus not qualify for a deduction to the extent that the monies must be repaid. It has been indicated that, even though certain elements of a trade, for example the intention to make a profit, repeated activities, planning and organisation, may be present in the case of a thief, the thief’s activities lack the key commercial character of a trade when it comes to sourcing the goods. Stolen monies and/or other goods are not obtained through normal commercial means and are not received as a reward for the provision of any goods or services. On that basis the act of embezzlement, fraud or theft does not constitute a trade. In a South African context a thief has another hurdle to cross, namely section 23(o) of the Income Tax Act No. 58 of 1962 (the Act), which provides that a taxpayer is not entitled to deduct expenditure that constitutes a fine charged or penalty imposed as a result of an unlawful activity carried out in South Africa or in any other country if that activity would be unlawful had it been carried out in South Africa. The possibility of deducting penalties was recently considered by the Upper Tribunal (Tax and Chancery Chamber) in the United Kingdom in the case of McLaren Racing Ltd v Revenue and Customs Commissioners [2014] STC 2417. 13 The McLaren motor racing team participates in the Formula One grand prix events that take place throughout the world. All teams participating in Formula One have concluded an agreement between themselves and the International Automobile Federation (the sport’s governing body) and the Formula One Association (a company engaged in the promotion of the Formula One world championship). This agreement is called the so-called Concorde Agreement. McLaren was held to have breached the International Sporting Code as its chief designer allegedly received confidential information pertaining to another Formula One racing team. Pursuant to this allegation, the McLaren racing team was ordered to pay a penalty of US$100 million in respect of a breach, less income which was lost as a result of it losing points in the so-called Formula One constructors’ championship. The ultimate penalty that was paid amounted to approximately £32 million. The question arose whether this penalty was deductible by the McLaren racing team on the basis of it constituting a disbursement or expense wholly and exclusively laid out or expended for the purposes of its trade or profession. In holding that the penalty was not wholly and exclusively laid out or expended for the purposes of McLaren’s trade, it was acknowledged that the penalty constituted a disbursement or expense. However, it was indicated that a deliberate activity which was not an unavoidable consequence of carrying on a trade did not constitute an activity carried on in the course of that trade. It was said: "In our view, a deliberate activity which is contrary to contractual obligations and the rules and regulations governing the conduct of the trade, which is not an unavoidable consequence of carrying on a trade and which could lead to the destruction of the trade, is not an activity carried on in the course of that trade." However, McLaren raised a different argument. It submitted that its trade constituted the design, manufacture and racing of motor cars. As part of such 14 trade it employs designers and engineers. It was a so-called 'occupational hazard' that employees might sometimes overstep the mark and act outside their scope of employment. This argument was also dismissed. The court refused to accept that, because an employer incurs a liability as a result of the acts of an employee, such liability is incurred in the course of the employer’s trade. This was based on the fact that the use of the confidential information did not constitute a normal or ordinary activity of McLaren. It did not become such an activity simply because it was carried out by an employee. It was furthermore held that the reason the McLaren racing team paid the penalty was not because it risked being excluded from the world championship (which might have destroyed its business operations) but because the McLaren racing team engaged in conduct that did not form part of its trade. Accordingly, the deduction of the penalty was refused. It is probable that a South African court might come to the same conclusion even though section 23(g) of the Act, which previously required deductible expenditure to have been laid out 'wholly and exclusively' for purposes of trade, similar to the requirement in the UK, has been amended. The section currently provides that expenses are deductible to the extent incurred for purposes of trade. Given the facts of the McLaren case, it would be unlikely that McLaren would be able to discharge the burden of proof that at least some amount was incurred for purposes of its trade. Since the penalty was intended to be a punishment, it still does not form part of the expenditure laid out for the trade of the taxpayer. Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr Interpretation Note No. 80 ITA: Sections 23(g) and 23(o) 15 INTERNATIONAL TAX 2397. Dividend payments to Holland Dividends paid by a South African company to a resident of the Netherlands may be subject to a dividend tax rate of 0% in South Africa. The premise of this interpretation is based on Article 10(10) of the Protocol issued under the Netherlands/South Africa double tax agreement (DTA), which provides as follows: “If under any convention for the avoidance of double taxation concluded after the date of conclusion of this Convention between the Republic of South Africa and a third country, South Africa limits its taxation on dividends as contemplated in subparagraph a) of paragraph 2 of this Article to a rate lower, including exemption from taxation or taxation on a reduced taxable base, than the rate provided for in subparagraph a) of paragraph 2 of this Article, the same rate, the same exemption or the same reduced taxable base as provided for in the convention with that third State shall automatically apply in both Contracting States under this Convention as from the date of the entry into force of the convention with that third State.” What this section means is that where South Africa has concluded a DTA with any other country after the date of conclusion of the Netherlands/South Africa DTA, and such other DTA provides for, inter alia, the complete exemption of dividends from dividends tax, the provisions of such DTA will automatically apply to the Netherlands/South Africa DTA, with the result that the dividends will similarly be exempt from dividend tax in SA. There are currently only 3 DTAs to which SA is a party to and which provide for the complete exemption of dividend tax, namely the DTAs with Cyprus, Kuwait and Oman. The test, therefore, is to determine whether any of these DTAs were concluded after the conclusion of the Netherlands/South Africa DTA. 16 The definition of the word “concluded” is absent from the DTAs, and the Netherlands/South Africa DTA does not shed any light on when the document is deemed to be “concluded”. According to the Netherlands/South Africa DTA, the document was signed on 10 October 2005, and the date of entry into force is 28 December 2008, with the provisions of the Convention having effect for taxable years and periods beginning on or after 1 January 2009. Having regard to the SARS website, the publication date of the document is 23 January 2009. The Kuwait/South Africa DTA, on which reliance is placed, was signed on 17 February 2004 and it was, according to the SARS website, published on 20 April 2007. In terms of Article 29 of the DTA itself, the date of entry into force is 25 April 2006. As a result of this confusion between all these dates, a view has been expressed that, because the actual convention between SA and Netherlands was concluded in 2005, and because the DTA between SA and Kuwait came into force 25 April 2006, which is after this conclusion date, it may have the result that reliance can be placed on the Kuwait/South Africa DTA to reduce the South Africa/Netherlands dividends tax rate to 0%. The writers have, in their previous article, issued a word of caution in that it is likely that this position will not be attainable. After having had further discussions with SARS, SARS’ view is that this is indeed the case. As stated above, it is evident from Article 10(10) that reliance can only be placed on the date of conclusion of a DTA. From a legal perspective, there are reported judgments in SA that have held that word ‘concluded’, along with other common usage variants, including the words “signed” and “reached”, all have to be interpreted in the context of the notion of finality, i.e. when the agreement or contract becomes ‘a binding act’ or a ‘final determination’. If this view is to be accepted in the context of any DTA, the date of conclusion of any DTA would be 17 the date when such DTA reaches “finality”. Such date could either be the date when the DTA was signed or the date of entry into force, depending on the facts and interpretation of each DTA, which would certainly require further, detailed analysis of each DTA. SARS’ interpretation, however, seems to be that the date of ‘conclusion’ of both the Kuwait/South Africa and South Africa/Netherlands DTAs are regarded as the date when they were signed and, therefore, the 0% tax rate in the Kuwait/South Africa DTA cannot apply to Article 10(10). Interestingly, however, similar to Article 10(10) of the Netherlands/SA DTA, Article 10(6) of the Sweden/South Africa DTA has a catch-all clause that “if any agreement or convention between South Africa and a third state provides that South Africa shall exempt from tax dividends (either generally or in respect of specific categories of dividends) arising in South Africa, or limit the tax charged in South Africa on such dividends (either generally or in respect of specific categories of dividends) to a rate lower than that provided for …. such exemption or lower rate shall automatically apply to dividends arising in South Africa and beneficially owned by a resident of Sweden … under the same conditions as if such exemption or lower rate had been specified…” What is notable is that Article 10(6) in the Sweden/South Africa DTA does not have any reference to the date of conclusion of the relevant DTA. This, undoubtedly, will create arguments that a 0% dividends tax rate should apply to dividends paid by a SA company to a Swedish resident shareholder which is the beneficial owner of such dividend. Of course articles of this nature are not intended to constitute advice, but rather to air important tax issues in order to stimulate debate. Prior to entering into any transactions it is, unquestionably, necessary to take detailed advice in relation both to the law and also to the taxpayer’s particular factual circumstances. A relevant issue in relation to the above legal analysis is that the public is not privy 18 to the bilateral negotiations involving DTAs, and therefore does not necessarily have all the information pertaining to what was intended by these clauses. It is also important to gauge the position of SARS in relation to such issues and part of the debate which our articles are intended to stimulate involves gaining insight into SARS’ position on these points. To this end our understanding of SARS’ position is that, as set out above, the Kuwait/South Africa DTA was not concluded after the South Africa/Netherlands DTA. (Editorial Comment: This article highlights the need for DTAs to be examined very carefully before application of their rules.) ENSafrica DTA : South Africa /Netherlands and South Africa / Kuwait TAX ADMINISTRATION ACT 2398. Mitigation of penalties and interest Judgment was handed down in the Tax Court on 18 November 2014 in the case of Z v The Commissioner for the South African Revenue Service (case number 13472), as yet unreported. The dispute concerned the calculation by the taxpayer of his capital gains tax liability arising pursuant to the disposal of shares. In 2007 the taxpayer disposed of his shares in a company for R841 million. In and around the time of the disposal of the shares, a company (A) instituted a damages claim against the taxpayer for an amount of R925 million which related to a transaction that took 19 place in 2003. Shortly after the damages action was instituted, the taxpayer agreed to pay A an amount of almost R700 million in full and final settlement of its claim. In determining his capital gains tax liability for the 2008 year of assessment, the taxpayer deducted a portion of the settlement amount paid to A from the purchase price received for the disposal of his shares, which the taxpayer regarded as his proceeds for purposes of paragraph 35 of the Eighth Schedule to the Income Tax Act No. 58 of 1962 (the Act). The Commissioner for the South African Revenue Service (Commissioner) disagreed with the taxpayer’s adjustment to the proceeds from the disposal of the shares and increased the proceeds by the portion of the settlement amount to arrive at the original proceeds of R841 million. Various technical arguments were raised by the taxpayer as to why the proceeds from the disposal of the shares should be reduced by a portion of the settlement amount paid to A. However, the Court agreed with the Commissioner’s findings that the inclusion of the full amount received by the taxpayer for the sale of the shares for the 2008 year of assessment is unassailable and the appeal must be dismissed. The purpose of this article is not to discuss the technical arguments surrounding the application of paragraph 35 of the Eighth Schedule. The interesting aspect of the case relates to the imposition of understatement penalties in terms of section 221 of the Tax Administration Act No. 28 of 2011 (the TAA) and interest in terms of section 89quat of the Act (as it read at the time). In the context of the understatement penalties imposed under the TAA, the Commissioner had imposed a penalty of R47 million on the basis of “reasonable care not taken” by the taxpayer or “no reasonable grounds existing for the tax 20 position taken”. The reasons cited by the Commissioner for reaching this decision was that “the legislation and the facts are clear”. The Court indicated that it was common cause that the TAA operates retrospectively and its provisions, including section 270(6D), should apply. It appears that the question of whether these provisions of the TAA and the decision to impose such penalty may be unconstitutional and / or subject to an administrative review application were not dealt with by the Court. In any event, if these issues were to be raised it would most likely have to be dealt with in a separate application to the High Court. The Court concluded that the taxpayer's conduct constituted a “substantial understatement” (as defined in the TAA) and the penalty falls to be reduced from 70% to 10%. In reaching this conclusion, we note that: the Court held at paragraph 40 that it was of the view that “having received advice, there were reasonable grounds for the appellant to take the tax position which it did. Nor can it be said that he did not take reasonable care – he did so by consulting the experts”; the Court referred to the Tax Court, in the United States of America case of Estate of Spruill v Commissioner [1987] 88 TC 1197, which had to determine whether the fraud penalty was appropriately applied to an understatement of estate tax resulting from a large under evaluation of property. The valuation in turn was determined with the advice of an attorney and an accountant and was based on an independent appraisal. The court, in rejecting the penalty, had the following to say (88 TC 1197: 1245): “When an accountant or attorney advises a taxpayer on a matter of tax law, such as whether a liability exists, it is reasonable for the taxpayer to rely on that advice. Most taxpayers are not competent to discern error in the substantive advice of an accountant or attorney. To require a taxpayer to challenge the attorney, to seek a “second opinion”, would nullify the 21 very purpose of seeking the advice of a presumed expert in the first place. . . .’ the Court held that while section 270(6D) provides that in certain limited circumstances, a senior South African Revenue Service official must, in considering an objection against the imposition of an understatement penalty, reduce the penalty in whole or in part if satisfied that there were extenuating circumstances, there was no evidence that there were extenuating circumstances which would warrant the reduction to below the understatement penalty. If one has regard to how Wepener J sought to apply the understatement penalty provisions in sections 221 and 270(6D), it is noted that: the Court firstly considered the taxpayer’s behaviour against the understatement penalty percentage table in section 223. Having regard to the penalty percentage table: o It was never contended that there was “gross negligence” or “intentional tax evasion” by the taxpayer. o On the basis that the taxpayer obtained professional advice, it was held that there were “reasonable grounds for the tax position taken” and it cannot be said that “reasonable care was not taken in completing the return”. o The tax return contained a “substantial understatement” as defined and, as result of the other behaviours being excluded - the penalty of 10% was imposed. Only after the Court had tested the taxpayer’s behaviour against the understatement penalty percentage table did it consider the application of section 270(6D); It may be debatable whether the correct approach is to consider section 270(6D) on its own (i.e. without first having regard to the penalty percentage table). 22 However, the approach adopted by Wepener J appears to be the most practical approach and avoids a judicial officer from having an unfettered discretion when making a determination as to the extent of the reduction of the penalty in terms of section 270(6D) (i.e. having regard to any extenuating circumstances). In the context of the request for remission of interest in terms of section 89quat of the Act (as it read at the time) it was also held that there is no reason not to find that the taxpayer’s reliance on advice was reasonable and any interest must be waived in full. It must be appreciated that the wording of section 89quat no longer refers to “reasonable grounds” being contended by the taxpayer. Section 89quat interest may now only be remitted in “circumstances beyond the control of the taxpayer”, which is far narrower than the previous wording of section 89quat. These findings by Wepener J that having received professional advice it cannot be said that there are “no reasonable grounds for the tax position tax” nor can it be said that “reasonable care [was] not taken in completing [a] return” should assist taxpayers when objecting to any understatement penalties imposed in terms of the TAA. Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr ITA: Section 89quat and Paragraph 35 of the Eighth Schedule TAA: Sections 221, 223 and 270(6D) TRANSFER PRICING 2399. Compliance conundrum By now, most South African taxpayers should be aware that when they enter into transactions with related parties who are not South African taxpayers, such transactions should be concluded on terms and prices that are at arm’s length in nature. The term “arm’s length” essentially indicates a position that two unrelated 23 parties would adopt in an open market transaction, as a willing buyer and willing seller. Critical to managing tax risk for any taxpayer that has transactions of this nature is being able to defend the transfer pricing (TP) position that they have adopted and the only way to adequately do so is through the preparation of TP policy documentation. What is Transfer Pricing documentation? As a starting point, it is important to highlight that, for now, it is not a statutory requirement to prepare TP documentation in South Africa – but there is a sting in the tail, and more on that later. Many years ago, SARS issued Practice Note 7 that provided guidance on their approach to TP and what TP documentation should cover. This Practice Note was largely based on the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) guidelines. In this process, SARS also pointed out that TP documentation should be relevant to each taxpayer’s circumstances and that it was not expected that a taxpayer should spend a disproportionate amount of money preparing TP documentation. Unfortunately, many taxpayers have taken a very aggressive position and have compiled a one or two page document that simply states what price they charge their related parties – although this may deal with inter-group pricing, it is not what the OECD and SARS would consider to be a TP document. TP documentation should provide the user (in most cases, SARS or the South African Reserve Bank) with insight into the following: the company and the group it forms part of, what products or services the group sells and some financial and statistical information like revenue, profit, number of employees, key locations etc. the industry the company and group operate in, the regional and global factors that affect that industry, the competitive landscape, etc. 24 the functions that the company undertakes, the various risks it assumes and the assets it uses to perform the said functions the TP methodology that the taxpayer has elected to use in determining and setting its prices and why it has not used any of the other recognised TP methods if appropriate (which in most cases it is), an economic analysis supported by benchmarking studies and analysis, the outcome of which is a pricing range commonly referred to as the inter-quartile arm’s length range. In the context of what SARS expects to see when a taxpayer says that they have prepared a TP document, when a taxpayer presents a one-page document to SARS, they arguably compromise their position even further. Critically, a taxpayer needs to discharge the onus of proof on why their pricing is considered to be at arm’s length and merely stating that one thinks that the price is fair does not do so. SARS, and any other revenue authority, will want to see objective data or market information that provides appropriate support. Coming back to the sting in the tail – when submitting an ITR14 tax return, the taxpayer is required to do so on an arm’s length basis. When answering questions relating to related party transactions with non-residents, the taxpayer is asked to confirm whether they have a TP policy document. If the taxpayer answers “no”, there is an immediate red flag, as SARS will question how the taxpayer knows that the tax return is submitted on an arm’s length basis when he has not prepared TP documentation. By not having adequate documentation or any documentation at all, the taxpayer is immediately on the back foot – a precarious position from which to engage with SARS! The alternative is to prepare appropriate TP documentation that could also serve to reduce any potential penalties that SARS may wish to impose on the finalisation of any TP audit by SARS. 25 Grant Thornton ITA: Section 31 2400. OECD’s BEPS Action Plan Transfer pricing and the concept of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Action Plan have been receiving attention in the South African media and Parliament for quite some time. Recently, on 19 November 2014, a session on transfer pricing was held during a meeting of Parliament’s mineral resources and finance committees. Presentations by the National Treasury and the South African Revenue Service (SARS) during this session provide insight into possible future transfer pricing legislation in South Africa. Most notably: Over the last three years, the SARS Transfer Pricing unit has audited more than 30 cases and made transfer pricing adjustments of over R20 billion with an income tax impact of R5 billion. A similar number of cases are currently in progress and others are in the process of being risk assessed. Legislative requirements for multinational enterprises (MNEs) to maintain specific transfer pricing documentation is to be considered. Legislative measures to address outcomes of the BEPS Action Plan (e.g. country-by-country reporting) are to be considered. Legislative framework for Advance Pricing Agreements (APAs) is to be considered, as such advance agreements on transfer pricing between taxpayers and SARS could alleviate the enforcement burden and encourage compliance. While tighter legislation may be needed, SARS recognizes the vital importance of a balanced response within the confines of domestic and international law, while not posing a deterrent to foreign direct investment. 26 Detailed discussion Background Over the past few months, transfer pricing and BEPS have been the subject of discussions by Members of Parliament on various occasions. In September 2014, one Member of Parliament called for a “comprehensive and clearly articulated law which forbids transfer pricing” during a beneficiation colloquium of Parliament’s portfolio committee on trade and industry.1 Earlier last year, transfer pricing and the possible instances of BEPS in the mining sector were a topic of discussion during a meeting of the Portfolio Committee on Mineral Resources.2 Against this background, the National Treasury and a research executive of SARS presented on South Africa’s Tax Policy Structure and Transfer Pricing and BEPS respectively during the meeting of Parliament’s mineral resources and finance committees on 19 November 2014. Corporate Income Tax, BEPS and Transfer Pricing The presentation by National Treasury on South Africa’s tax policy structure (with a focus on corporate income tax) and the presentation by the SARS research executive provided a brief overview of the current corporate income tax base and an explanation of what transfer pricing entails. While the presentations were part of the meeting of the mineral resources and finance committees, it was noted that the extractive industry, from a transfer pricing and BEPS perspective is essentially no different than any other sector and is therefore not the sole cause of concern. Measures against BEPS The issues of transfer pricing and BEPS were touched upon in the context of South Africa’s need for foreign investment in light of the twin budget and current account deficits. Most significant foreign investment comes from MNEs, which are inherently engaged in cross-border transactions with related parties, e.g. through the sale of goods, intangibles transactions, the provision of services and the provision of funding. While such cross-border transactions are in principle 27 beneficial, they can result in abuse when used to shift profits in order to exploit differences in tax rates between the countries involved. In other words, transfer pricing itself is an essential feature of cross-border activities of MNEs and only “transfer mispricing” is not acceptable. The threat of BEPS for the corporate income tax base and the tax implications of cross-border transactions and international taxation were addressed. It was noted that South Africa plays a key role as a member of the BEPS Bureau Plus and that a number of measures have already been implemented to address BEPS, some even before the BEPS Action Plan was released by the OECD in July 2013.3 Such measures include rules and regulations regarding transfer pricing, controlled foreign companies, interest deduction limitations, hybrid instruments and entities, the digital economy and exchange of tax information. In addition, the Transfer Pricing unit established at the Large Business Centre of SARS was mentioned as one of the responses to the threat of BEPS. In this regard, it was noted that: Audits require scarce skills, are resource intensive, requiring understanding of company, industry, global value chain, strategic decision making, business models, etc. and take at least 18 months. As a result of limited resources there is a focus on strategic auditing – high risk, high value transactions. Over the last three years the Transfer Pricing unit has audited more than 30 cases and made transfer pricing adjustments of just over R20 billion (as a conservative measure) with an income tax impact of R5 billion. A similar number of cases are currently in progress and others are in the process of being risk assessed. The extractive industry is no different to any other sector and the industry is not the sole cause of concern. However, due to the size and significance of this sector in South Africa, it remains a key area of focus for SARS. 28 Implications SARS indicated it takes the protection of the South African tax base seriously and there will be an ongoing focus on strengthening SARS capacity and capability. At the same time, there will be a continual review of audit and risk assessment processes and an ongoing dialogue with MNEs on levels of tax compliance. On an international level, SARS will continue its participation in and co-operation with inter alia the OECD, the United Nations, the African Tax Administration Forum (ATAF) and the World Bank. It will also continue its co-operation with other tax administrations and review international approaches to the extractive industry. With respect to the future of transfer pricing and possible measures against BEPS, it was specifically mentioned that: Legislative requirements for MNEs to maintain specific transfer pricing documentation is to be considered. Legislative measures to address outcomes of the BEPS Action Plan (e.g. country-by-country reporting) are to be considered. Legislative framework for Advance Pricing Agreements (APAs) is to be considered, as such advance agreements on transfer pricing between taxpayers and SARS could alleviate the enforcement burden and encourage compliance. As a closing remark, SARS noted there is no easy solution and it has to work within the confines of both domestic and international law. While tighter legislation may be needed, SARS recognized it is vitally important to respond in a manner that is balanced and does not pose a deterrent to foreign direct investment. In this regard, it is worth noting that additional measures may come from the Davis Tax Committee following its review of the corporate tax system with special reference to tax avoidance (e.g., base erosion, income splitting and profit shifting).4 29 Endnotes 1. Clamour to end transfer pricing abuse, Linda Ensor, 4 September 2014. See http://www.bdlive.co.za/business/2014/09/04/clamour-to-end- transfer-pricing-abuse. 2. Portfolio Committee on Mineral Resources, National Assembly, Wednesday 2 July 2014. 3. See http://www.oecd.org/ctp/BEPSActionPlan.pdf for more information. 4. On 17 July 2013, the South African Minister of Finance announced the members of a tax review committee (the Davis Tax Committee) to inquire into the role of the tax system in the promotion of inclusive economic growth, employment creation, development and fiscal sustainability. See http://www.taxcom.org.za/ for more information. Ernst & Young Inc. ITA: Section 31 SARS NEWS 2401. Interpretation notes, media releases and other documents Readers are reminded that the latest developments at SARS can be accessed on their website http://www.sars.gov.za. Editor: Mr P Nel Editorial Panel: Mr KG Karro (Chairman), Dr BJ Croome, Mr MA Khan, Prof KI Mitchell, Prof JJ Roeleveld, Prof PG Surtees, Mr Z Mabhoza, Ms MC Foster The Integritax Newsletter is published as a service to members and associates of The South African Institute of Chartered Accountants (SAICA) and includes 30 items selected from the newsletters of firms in public practice and commerce and industry, as well as other contributors. The information contained herein is for general guidance only and should not be used as a basis for action without further research or specialist advice. The views of the authors are not necessarily the views of SAICA. 31