thomas

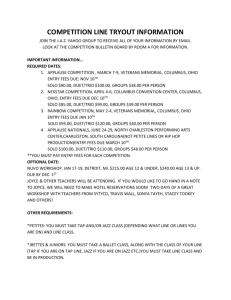

advertisement