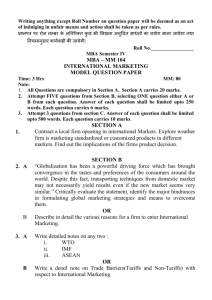

Proposta de Tese

advertisement