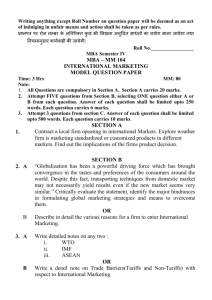

Marketing Strategy-Performance Relationship: An

advertisement