The Rubicon Theory of War

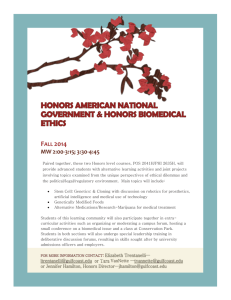

advertisement