FORENSICS JOURNAL - Stevenson University

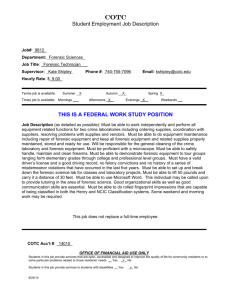

advertisement