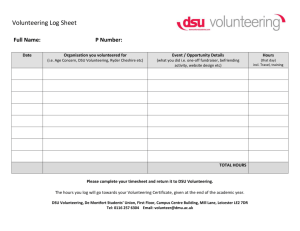

volunteering and social activism

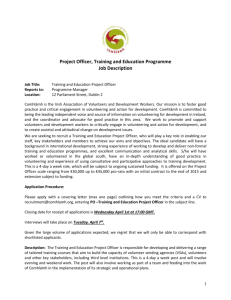

advertisement