Nutritional Merits of Home Grown Vs. Store

advertisement

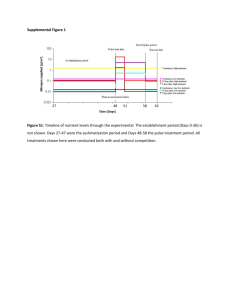

Nutritional Merits of Home Grown Vs. Store Bought Produce This paper addresses the nutritional merits of eating fresh, home grown produce from an AeroGarden as opposed to commercially available produce from a grocery store. A look into the scientific facts about the nutrition of produce on store shelves, creates an uncomfortable revelation about the food we’re serving our families. Four big factors that impact the nutritional value of the produce you eat: l l The ripeness of the produce The length of time since harvest l l The varieties chosen The harvesting methods The Problem Independent Distributor Nothing compares to the juicy flavor of a tomato picked fresh off the vine and eaten right in the garden. Today’s global food system ensures that we can find ripe tomatoes any day of the year in any store across the country but the flavor of those tomatoes is often a far cry from that deep red, vine ripened fruit in your garden. Moreover the fresh produce we find in our grocery stores today actually contains fewer nutrients than the same types of produce did just 30 years ago. In 1951, an adult woman could meet her daily requirements of vitamin A by eating two peaches. By 2002, she would need to eat 53 peaches to obtain the same amount of vitamin A (Ramberg and McAnnelley, 2002). Commercial agriculture of the 21st century seems focused on enhancing shelf life of produce, often at the expense of taste and nutrition. This means that maximizing your nutrient dollar in our current grocery store climate is a daunting task and can result in produce lacking in both flavor and quality. Ripeness Impacts Nutritional Value How can our advanced technological world create fruits and vegetables that contain fewer nutrients than they did in the past? Several things are to blame. First in order to accommodate the 1500-2500 mile trip that the average produce item travels to reach your grocery cart, the fruit must be harvested well before it is ripe (Pirog et al., 2001). This premature harvest interrupts the natural ripening process and limits the fruit’s ability to develop its full nutrient potential. Studies have shown that tomatoes harvested green have 31% less vitamin C than those allowed to ripen on the vine (Lee and Kader, 2000). Vine ripened red peppers too, have about 30% more vitamin C than green peppers (Howard et al., 1994). It is not just vitamin C content that is reduced, in fact vine ripened tomatoes contain more of the important antioxidants beta carotene and lycopene than those harvested prematurely (Arias et al., 2000). Continued on Next Page The Impact of Storage and Travel Times on Nutritional Value A third important factor in the loss of nutrients in our food is the storage and travel times that produce must endure while being shipped such great distances. All fruits and vegetables steadily lose vitamins while in storage, even at optimal temperatures. Lettuce loses 46% of some key nutrients within seven days of cold storage. Spinach loses 22% of lutein and 18% of beta carotene content after just eight days of cold storage (Ramberg and McAnnelley, 2002). Culinary herbs, when used fresh, contain significant amounts of antioxidants. These antioxidants decrease rapidly after harvest making it difficult to reap the full health benefits of fresh culinary herbs with products from commercial grocery stores (Bottino, 2010). Plant Variety and Nutritional Value One of the biggest determinate of nutritional value is plant variety. Even among salad greens, the nutritional value of many nutrients can more than double from one variety to the next. However, most commercially available fresh foods today are chosen for their ability to ship well, store well, and continue to “look fresh” while waiting for a sale to consumers. Often, these choices are made instead of choosing foods with the best flavor or nutrition. Tomatoes are the easiest example. Today’s store-bought tomatoes are varieties picked for their ease of shipping and for their ability to turn red even when unripe. They are uniformly round, hard and, many would say, flavorless – perfect for shipping and storing on-shelf – but not great for eating! Harvesting and Nutrition The harvesting methods used in the field and subsequent handling of the fruits and vegetables also affect the ultimate nutrient contents achieved. Mechanical harvesting methods used in most commercial farms today, have a higher probability of bruising or injuring the produce. This type of damage can accelerate nutrient loss or even affect the ability of the fruit to fully ripen (Lee and Kader, 2000). The vitamin C content in bruised portions of tomato fruits was found to be 15% less than that of non-damaged tomato tissue (Moretti et al., 1998). Lettuce leaves sliced by sharp knives had 25-63% lower vitamin C levels than lettuce torn manually (Barry-Ryan and O’Beirne, 1999). Continued on Next Page The perceived convenience of global food sourcing and mass shipping of produce to achieve lower prices has been a detriment to our diets and our planet. Not only has the nutrient availability of fruits and vegetables decreased, but there is an environmental cost of transporting produce such great distances. Eleven percent of the energy used in the US food system is spent on transportation (Pirog et al., 2001). This 11% adds up to over 166 million BTU’s of fuel used just on transporting food from farm to table in 2009 (US EIA 2010). What is the solution to this problem? Ideally, obtain your produce from local growers or even better, grow your own. Nothing compares with the ability to pick a tomato and snip some fresh basil to go with it right in your own home. Of course not everyone owns a farm, or even has access to an outdoor space capable of supporting a garden. Seasonal restrictions also limit your ability to grow produce at home, even for experienced gardeners. Indoor small scale hydroponics such as the AeroGarden may provide the best answer for year round fresh produce at home. With home grown produce, you control the time of harvest and obtain perfect, ripe fruits and vegetables every time. There is no harvesting or handling damage when growing at home, all produce is handled gently by only you before it is prepared and consumed. The ability to pick and eat within minutes means that your home grown produce supplies you with the most nutritionally rich fruits and vegetables available, maximizing your nutrient dollar and providing your family with the healthiest produce possible. Growing fruits and vegetables at home allows you to combat commercial agriculture’s assault on the nutrient value of your food while keeping it affordable and fun for you and your family. Continued on Next Page Commercial Produce Home Grown Produce Seed varieties selected for transportability and shelf life, not nutrient content or flavor Nutrient rich, flavorful seed varieties Growing conditions (temperature, light, fertilizer applications) not always consistent or optimal for maximizing nutritional content Consistent, optimal levels of light, fertilizer and temperature to create nutritionally rich produce Harvested using mechanical methods, often causing injury and nutrient loss Hand-picked & handled just by you Often prematurely harvested to prolong shelf life, the produce is unable to reach nutritional peak Harvested at the peak of ripeness, maximizing nutrient content Can travel 1500 miles or more from farm to table, losing nutrients each day along the way Eaten on day of harvest, no travel necessary References Arias, T., Lee, C., Specca, D. and Janes, H. (2000). Quality comparison of hydroponic tomatoes (Lycopersicon esculentum) ripened on and off vine. Journal of Food Science, 65, 545-548. Barry-Ryan, C. and O’Beirne, D. (1999). Ascorbic acid retention in shredded iceberg lettuce as affected by minimal processing. Journal of Food Science, 64, 498-500. Bottino, A (2010). Yield and Quality of Green Leafy Vegetables in Postharvest. Universita Degli Studi Di Napoli Federico II. Howard, L., Smith, R., Wagner, A., Villalon, B. and Burns, E (1994). Provitamin A and ascorbic acid content of fresh pepper cultivars (Capsicum annuum) and processed jalapenos. Journal of Food Science, 59, 362-365. Lee, S. and Kader, A. (2000). Preharvest and postharvest factors influencing vitamin C content of horticultural crops. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 20, 207-220. Moretti,C., Sargent, S., Huber, D., Calbo, A. and Puschmann, R. (1998). Chemical composition and physical properties of pericarp, locule, and placental tissues of tomatoes with internal bruising. Journal of American Society of Horticultural Science, 123, 656-660. Pirog, R., Van Pelt, T., Enshayan, K. and Cook, E. (2001). Food, Fuel and Freeways: An Iowa Perspective on How Far Food Travels, Fuel Usage and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Retrieved May 5, 2011 from Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture www.leopold.iastate.edu Ramberg, J. and McAnnelley, B. (2002). From the Farm to the Kitchen Table: A Review of the Nutrient Losses in Foods. Glycoscience and Nutrition, 3 (5), 1-12. U.S. Energy Information Administration (2010). Annual Energy Review 2009. Retrieved May 10, 2011 from www.eia.doe.gov. REV052711