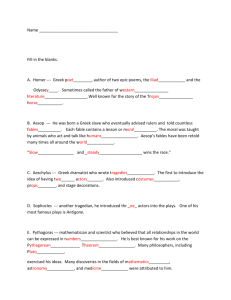

Guide to Ancient (Greek)Thought

advertisement

R. Zaslavsky©2013

Guide to Ancient (Greek) Thought

“Study in antiquity differed from that current in modern times: it was nothing less than the thorough education of

the natural consciousness. Testing itself against every separate part of its existence, and philosophizing about

everything it encountered, it made itself into a generality that was active through and through. In modern times, on

the other hand, the individual finds the abstract form ready-made: the exertion of grasping it and appropriating it is

rather more the unmediated production of the inward and the cut-off generation of the general than the emergence of

the general out of the concrete and the multiplicity of existence.” [G. W. F. Hegel (1770-1831), Phenomenology of the

Spirit (1807), Preface, tr. Walter Kaufmann, excerpt]

“For I opine Hesiod and Homer to come to be in their prime four hundred years older than I, and not more; and these

are the ones having made the theogony for the Greeks, even giving the gods their nicknames and dividing-up their

honors and arts and signifying their looks.” [Herodotus II. 53; tr. mine]

Homer

(fl. c. 750 BC)

Iliad (the culture hero)

Odyssey (the nature hero)

the work of Homer hovers over the entire

development of ancient Greek thought

Hesiod

(fl. c. 8th-7th century BC)

Works and Days:

the five ages of humanity (golden, silver, bronze,

heroic, and iron)

strife as fundamental (the two strifes, one negative

and one positive: strife as fighting; strife as

striving)

manual of agriculture: the natural cycle as the best

human horizon

Theogony:

the genealogy of the gods

Thales of Miletus

(c. 634-c.546 BC)

made the first map of the world

astronomer: predicted a solar eclipse (585 BC)

first person to demonstrate a geometrical proposition (called the theorem of Thales by Euclid)

became the stereotype of the philosopher

first to ask the question “what is the ruling-beginning (archê) of all things?” [i.e., instead of asking, “who

made the world?” he asked “what is the world?”]

his answer to that question was “the archê of nature is water”

Anaximander of Miletus

(611-547 BC)

the archê is not water or any other corporeal

element: rather, it is what he called the unlimited

(apeiron) 1

Anaximenes of Miletus

(585-525 BC)

the archê is air, which is differentiated through the

processes of condensation and rarefaction

Pythagoras of Samos

(fl. 6th century BC)

institutionalized the distinction between esoteric (true inner) and exoteric (adjusted outer/public)

teachings

formed a community of initiates, thereby welding together the quest for knowledge and the proper mode

of living2

the archê of all things is number

every number is represented by a figure, a field; therefore, the archê is limited (finite)

the basis of this teaching was the ratios that constitute musical harmony

therefore, form, or structure, is the basis of all things

1

The Latin equivalent of this is infinitum, literally, “unlimited,” but sometimes translated as “infinite.”

Therefore, when one speaks of Pythagoras, one actually means Pythagoreans. According to Diogenes

Laertius (VIII. 2. 8), Pythagoras compared life to an athletic competition: of the three types of humans

there (the competing athletes, the vendors, and the spectators), the highest were the spectators (i.e., the

lookers or contemplators).

2

1

R. Zaslavsky©2013

Xenophanes of Colophon

(c. 568-c. 474 BC)

there is only one god: the first rational

monotheism3

Parmenides of Elea

(c. 512-c. 440 BC)

for him, the question

becomes “what does it

mean to be?/what is

being?/what is “is”?

in his poem, he

describes the journey

from ignorance to

knowledge as a chariot

ride to see an

unspecified goddess

who teaches him the

way of being

being is characterized

by radical homogeneity

(one of the two ultimate

competing views of the

world: see Heracleitus)

the oneness of being

being is ungenerated,

imperishable, whole,

complete, unique, and,

altogether contiguous;

in short, being is one

he asks not about the

beings but about being

qua being

what is the beingness of

beings/what is the

isness of what is?

nullifies becoming

to intellect and to be are

the same

Heracleitus of Ephesus4

(fl. 6th-5th century BC)

the archê of all things is not a something

all things always flow: being is characterized by

radical heterogeneity (one of the two ultimate

competing views of the world: see Parmenides )

the manyness of being

one cannot go into the same river twice 5

“war is the father of all things, and king of all

things” (Fragment 53, tr. mine) [i.e., all is constant

motion and turmoil]

Zeno of Elea

(c. 492-c. 430 BC)

student of Parmenides

Zeno’s paradoxes to

demonstrate the

impossibility of motion

(what Heracleitus calls

“flow”): Achilles and

the tortoise; the

dichotomy; the arrow;

the stadium

Empedocles of Acragas

(c. 490-c. 430 BC)

the four corporeal

elements (somatika

stoicheia) are the

building blocks of all

things: fire, air, water,

earth

each element is like

beingness in

Parmenides

attempt (inadequate) to

fuse heterogeneity and

homogeneity

the motive forces (the

archai) of the cosmos are

friendship and

contention (a refinement

of Hesiod’s account)

3

Leucippus of Miletus

and

Democritus of Abdera

(fl. early 5th century BC)

unalloyed atomism: the

archai are atoms,

unlimited

(apeiron/infinite) in

number

to restore the

intelligibility of motion

that the Eleatics

(Parmenides and Zeno)

denied, they added the

presence of the empty

(which some translate

as “the void”) to their

theory of elements

“But if oxen and horses or lions had hands, or [if they had it in them] to write with hands and to

complete the very deeds/works [erga] which men [do], [then] horses would write the Looks [ideai] of

gods similar to horses and oxen similar to oxen and would make the bodies [of their gods] suchlike as

each themselves had body-builds.” (Xenophanes, Fragment 15, tr. mine)

4

In Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors, as I understand it, altering his source in Plautus by doubling the

number of twins and shifting the locale from Herculaneum to Ephesus is meant to indicate that the play

is the presentation of what it would be like to live in a Heracleitean world. As such, it is a great

epistemological comedy.

5

Cratylus, a disciple of Heracleitus, reformulated this more radically thus: “one cannot go into the same

river once.”

2

R. Zaslavsky©2013

Anaxagoras of Clazomenae

(c. 500-c. 428 BC)

there are two archai: the unlimited (apeiron) [the

matter of the cosmos] and intellectual-intuition

(nous) [the primal motive force]

the sun is a stone, and the moon is earth, i.e.,

neither is a god

Herodotus of Halicarnassus

(c. 484-c. 425 BC)

Inquiries6

the book is ostensibly an account of the Persian

Wars (500/499-449 BC)

as he presents that war, he provides a cultural atlas

of the known world based both on his own

sightseeing (theoria: contemplation/spectating) and

on hearsay (akoê)

in a sense, he is presenting himself as the new

prose Homer, combining in one work both the Iliad

and the Odyssey: he is the new Odysseus

recounting the new and bigger equivalent of the

Trojan War

as he says, his goal is to preserve “the big and

wondrous deeds, the ones having been shown

forth by Hellenes and by barbarians” (I. 1, tr. mine)

the tentacles of causation of the Persian Wars are

presented as reaching back to the distant past and

around the distant present

the book could be described as an account of events

supplemented by a comprehensive cultural

anthropology (in the literal sense of a rational

account of humans)

Contemporaries of Socrates: Sophists7

Protagoras of Abdera

(c. 490-c. 420 BC)

the human (anthropos) is the measure of all things,

of the things that are, how they are, and of the

things that are not, how they are not” (Fragment 1,

tr. mine): what seems to a human to be so, is so {so

that what Parmenides called the “way of opinion”

is for Protagoras, the true way [one could call this

political Heracleiteanism]

sometimes described as a thoroughgoing relativist

“about the gods, I do not have [any basis] to

envision either how they are or how they are not”

(Fragment 4, tr. mine): agnosticism

taught his students how “to make the worse speech

(logos) the better (i.e., how to win arguments by

hook or by crook)

Gorgias of Leontini

(c. 486-c. 378 BC)

persuasion is omnicompetent and omnipotent

truth always will crumble under the power of

persuasiveness

Hippias of Elis

(c. 485-c. 415 BC)

virtuoso orator

accused (not formally) of atheism

Prodicus of Ceos

(c. 465-c. 390 BC)

Heracles’s choice between the paths of virtue and

vice

6

The title of Herodotus’s work is Historiai in Greek. This has been traditionally translated Histories.

However, that translation is misleading. The Greek word historiê means “inquiry.” The earliest

translators, who rendered it as “history,” were not wrong to do so, since one could then still refer to

science as natural history (i.e., a scientific inquiry into nature). It is only since the 19th century that the

translation has become problematic because contemporary scholars—those who refer to Herodotus as

“the father of history” (pater historiae: Cicero, De legibus, I. 5)—assume that he is a historian in the modern,

especially the post-Hegelian, sense. That is a misleading assumption. Those who have adopted Cicero’s

phrase have taken it out of the context that shows that it is not history in the modern sense.

7

Sophists were those who took money for teaching, something scorned by the Platonic Socrates. The

word sophistês (sophist) in Greek has a range of meaning from “professional wise person” to “wise guy.”

The descendants of the sophists are teachers and professors.

3

R. Zaslavsky©2013

Socrates of Athens

(469-399 BC)

wrote nothing: in that sense, he is the only truly pure philosopher in Western history

virtually nothing is known about him in the strictly historical sense: most of what is known about him is

inferred from the play The Clouds, by his contemporary Aristophanes, and from the dialogues of his

students, Plato and Xenophon8

the teaching of his predecessors culminated in him, and his successors were elaborators of his teaching

he was said to have shifted the focus of philosophy from the cosmos (physics/cosmology) to the human

things (anthropology, in the literal sense).9

tried by the city of Athens and put to death by poisoning (hemlock): Athens’s first crime against

philosophy

Contemporaries of Socrates: Non-Sophists

Thucydides of Athens

(c. 471/460-c. 399 BC) 10

Athenian general, banished for

failing to achieve a desired

objective

his account of the Peloponnesian

War (431-404 BC) was left

untitled at his death

sets himself against both Homer

and Herodotus (cf. I. 21)

he sets himself the task of

demonstrating that the

Peloponnesian War was the

“biggest motion” (i.e., the war of

wars, bigger in importance than

either the Trojan War or the

Persian Wars: I. 1, tr. mine)

he boldly declares to be writing

for posterity, saying that what he

writes “is set down as a

possession unto always” (I. 22, tr.

mine)

what he writes looks more like

the contemporary notion of

history, but it is equally a

significant work of political

philosophy

Aristophanes of Athens

(c. 447-c. 387 BC)

comic playwright

politically conservative

The Clouds: a satirical critique of a

younger Socrates, a Socrates still

focused on the study of physics

and caricatured as a sophist

Critias of Athens

(c. 480-c. 403 BC)

Plato’s uncle

wrote about politics and

composed plays

“the most beautiful look in males

is the female, but in turn the

contrary in females [i.e., the most

beautiful look in females is the

male]” (Fragment 48, tr. mine) 11

Hippocrates of Cos

(c. 460-c. 375 BC)

practiced what would now be

called holistic medicine

The Hippocratic Oath

8

Contemporary classics and philosophy teachers tend to denigrate Xenophon and to elevate Plato. That is

a mistake. One should keep in mind the words of the consummate classicist, John Milton, who refers to

“the divine volumes of Plato and his equal, Xenophon.” [Apology for Smectymnuus, near the end]

9

Cf. Cicero, Tusculan Disputations, V. 10, tr. mine: “However, Socrates first [i.e., is the first one who] has

called down philosophy from the heaven and has placed [it] in towns and even has introduced [it] into

homes and has activated [it] to search about life and habits and good and bad things.” (Socrates autem

primus philosophiam devocavit e caelo et in urbibus conlocavit et in domus etiam introduxit et coegit de

vita et moribus rebusque bonis et malis quaerere.)

10

According to scholars in late antiquity, Thucydides was born in 471 BC. Modern scholars have

conjectured the later date of 460 BC. No one knows with certainty which it is.

11

This is a little known, but extremely important, principle for understanding visual representation in the

history of art.

4

R. Zaslavsky©2013

Students of Socrates:

Plato of Athens

Xenophon of Athens

(c. 428-c. 347 BC)

(c. 430-c. 355 BC)

wrote 35 dialogues12 and 13 letters13

soldier, chronicler, and philosopher

dialogues are plays and should be read as such14

wrote dialogues and accounts of contemporary and

in all but two of the dialogues (Laws, Epinomis),

near contemporary events

Socrates is an interlocutor (major or minor)

Socratic dialogues: Recollections (= Memorabilia),

tried to fuse Heracleitean sensory (aisthetic)

Oikonomikos,17 Symposium, Apology

heterogeneity with Parmenidean intellective

Non-Socratic dialogue: Hiero or Tyrannikos18

(noetic) homogeneity

Representative other works: Anabasis,19 Cyropaedia20

the dramatic character of the dialogues makes it

impossible to read off from them in a direct way

any so-called Platonic teaching15

exoteric teaching vs. esoteric teaching (cf.

Pythagoras) 16

the dialogues are meant to be a prompt: the reader

must be a silent interlocutor in a conversation that

the conversation in the dialogue inspires.

With respect to the dialogues of Plato and Xenophon, it is almost as if the two thinkers came to an

agreement that Plato would do the bulk of the work of presenting the fictionalized Socrates, while

Xenophon would address the rest. This would have left Xenophon free to write his chronicle, his

Cyropaedia (a manual of politics and pedagogy), among other things (e.g., hunting, equestrianism).

Student of Plato:

Aristotle of Stagirus

(384-322 BC)

studied with Plato for twenty years

his teaching has the form of expositions and lecture

notes that are comprehensive in scope: he wrote on

ethics, politics, biology, poetics, physics,

psychology, logic and language, and rhetoric

tutored Alexander the Big (356-323 BC) 21

four causes: material, formal, efficient, final

matter and form

differences between Aristotle and Plato are only

apparent, not genuine

fled Athens to prevent, as he said, Athens from

committing a second crime against philosophy

Student of Aristotle:

Alexander the Big of Macedon (326-323 BC)

his conquest ends the Greek period and ushers in

the Hellenistic period, a period marked by

cosmopolitanism and syncretism

Euclid of Alexandria (fl. 300 BC): Elements

Archimedes of Syracuse (c. 287-c. 212 BC)

12

Nothing is known with historical certainty about when each of the dialogues was written. Therefore,

any scholar who orders them chronologically (rather than internally dramatically) is creating an arbitrary

framework based on prejudgments and presuppositions for which there is no genuine justification.

13

Of these, the two most important are the second and the seventh.

14

In Aristotle’s Poetics, they are listed as dramatic works.

15

The dialogues must be read as one would read a Shakespearean play. One should no more simply

attribute the statements of Socrates (or Timaeus, or Parmenides) to Plato than one would attribute the

statements of Macbeth (or Othello) to Shakespeare.

16

There is no way to capsulize the content of the dialogues of either Plato or Xenophon. I simply will say

that most of what one finds in standard textbooks, histories of philosophy, and professorial lectures is

incomplete or misleading at best, totally erroneous at worst.

17

This means literally “a person skilled in (or knowledgeable about) the law of the household.” It is the

source of the word “economics.”

18

Hiero is a name. “Tyrannikos” means literally “a person skilled in (or knowledgeable about) tyranny.”

19

This is Xenophon’s account of his military service in the Persian expedition.

20

This means The Education of Cyrus.

21

His name is ı ÉAl°jandrοw µ°ga˚, which literally means “Alexander the Big.” In Greek and Latin, the

adjective “big” (megas [Gk.], magnus, [Lat.]) can mean “big in size,” “big in age,” “big in importance,” etc.

I prefer to render it always the same way.

5

![Xenophon (c.430—c.350 BCE) Page 1 of 3 Xenophon [Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/011234393_1-3c8362d360191952f417219201185636-300x300.png)