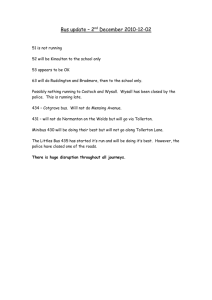

Evaluation Study of Demand Responsive

advertisement