AP Microeconomics – Chapter 7 Outline I. Learning Objectives—In

advertisement

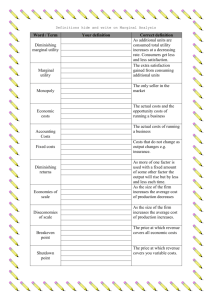

AP Microeconomics – Chapter 7 Outline I. Learning Objectives—In this chapter students should learn: A. Why economic costs include both explicit (revealed and expressed) costs and implicit (present but not obvious) costs. B. How the law of diminishing returns relates to a firm’s short‐run production costs. C. The distinctions between fixed and variable costs and among total, average, and marginal costs. D. How economies of scale link a firm’s size and its average costs in the long run. II. Economic Costs A. Economic cost is the payment a firm must make to obtain and retain the services of a resource. It is paid to resource suppliers to attract those resources away from alternative uses. Payments may be explicit or implicit. (Recall opportunity costs in Chapter 1.) B. Explicit costs are payments to resource suppliers for resources that the firm does not already own. In the text’s example, this would include cost of the T‐shirts, the clerk’s salary, and utilities, for a total of $63,000. C. Implicit costs are the opportunity costs of using the resources that the firm already owns to make the firm’s own product, rather than selling those resources to outsiders for cash. In the text’s example, this would include forgone interest, forgone rent, forgone wages, and forgone entrepreneurial income, for a total of $33,000. D. Normal profits are considered an implicit cost because they are the minimum payments required to keep the owner’s entrepreneurial abilities self‐employed. This is $5,000 in the example. E. Economic or pure profits are total revenue minus all costs (explicit and implicit, including a normal profit). Figure 7.1 illustrates the difference between accounting profits and economic profits. The economic profits in the example in the book are $24,000 (after $63,000 + $33,000 are subtracted from $120,000). F. The point of zero economic profit is an important threshold in business decision making. AP Microeconomics – Chapter 7 Outline 1. If the firm exactly breaks even with zero economic profit, it is earning enough to cover all explicit and implicit costs, including normal profit it could have earned in another enterprise. Therefore, the firm has no incentive to change. 2. If the firm earns an economic profit, it is earning more than it could in alternative enterprises, and the firm may choose to expand. Further, other entrepreneurs will be attracted by the incentive of economic profit and more firms may join the industry. 3. If the firm earns an economic loss, it is earning less than it could in alternative enterprises. The firm may reduce output or shut down entirely, and other entrepreneurs will not be attracted to the industry. 4. As a result, allocative efficiency increases as production increases for firms with greater net benefits and decreases for firms with lesser net benefits. G. The short run is a period too brief for a firm to alter its plant capacity, yet long enough to permit a change in the degree to which the plant’s current capacity is used. Short‐run costs are the wages, materials, and utilities used for production in a fixed plant. H. The long run is a period long enough for a firm to adjust the quantities of all of the resources that it employs, including plant capacity. Long‐run costs are all costs, including the cost of varying the size of the plant. The long run also includes enough time for new firms to enter the industry or existing firms to exit the industry. III. Short‐Run Production Relationships A. Short‐run production reflects the law of diminishing returns, which states that as successive units of a variable resource are added to a fixed resource, beyond some point the marginal product attributable to each additional unit of the variable resource will decline. B. CONSIDER THIS … Diminishing Returns from Study 1. The first hour of additional study for a course can significantly increase course learning. 2. Additional hours of study add learning, but at smaller amounts for each additional hour, until additional learning falls to zero. C. Table 7.1 below, presents a numerical example of the law of diminishing returns. AP Microeconomics – Chapter 7 Outline 1. Total product (TP) is the total quantity, or total output, of a particular good produced. 2. Marginal product (MP) is the extra output associated with adding a unit of a variable resource, such as labor. 3. Average product (AP) is output per unit of labor input. 4. Figure 7.2 (Key Graph) illustrates the law of diminishing returns graphically and shows the relationship between marginal, average, and total product. AP Microeconomics – Chapter 7 Outline a. The first few workers hired bring increasing marginal returns, because specialization would occur and the equipment would be used more efficiently. As the marginal product is greater than the average product, it pulls up the average product, and total product rises quickly. b. At some point, marginal product begins to diminish as specialization wears off and overcrowding leaves workers waiting to use the fixed amount of equipment. The marginal product decreases (but remains positive), so the rate of increase in total product stops accelerating and it grows at a diminishing rate. As long as the marginal product is greater than the average product, average product continues to increase; however, the average product declines once the marginal product slips below average product. c. Negative marginal returns occur when overcrowding actually causes production to decline when additional workers are hired. Total product declines when the marginal product becomes negative, and average product falls because the marginal product is lower than the average product. D. The law of diminishing returns assumes all units of variable inputs—workers in this case—are of equal quality. Marginal product diminishes not because successive workers are inferior, but because more workers are being used relative to the amount of plant and equipment available. IV. Short‐Run Production Costs A. Fixed, variable, and total costs are the short‐run classifications of costs; Table 7.2 illustrates their relationships. 1. Fixed costs are those costs that do not vary with changes in output. They include rental payments and interest on the firm’s debts. 2. Variable costs are those costs that change with the level of output. They include payments for materials, fuel, power, transportation services, and most labor. 3. Total cost is the sum of fixed cost and variable cost at each level of output (Figure 7.3). AP Microeconomics – Chapter 7 Outline Figure 7.3 B. Per‐unit or average costs are shown in Table 7.2, columns 5 to 7. 1. Average fixed cost is the total fixed cost divided by the level of output (AFC = TFC/Q). It will decline as output rises. 2. Average variable cost is the total variable cost divided by the level of output (AVC = TVC/Q). Due to increasing and then diminishing returns, the average variable cost is depicted as a U‐shaped curve. 3. Average total cost is the total cost divided by the level of output (ATC = TC/Q), sometimes called unit cost or per‐unit cost. Note that ATC also equals AFC + AVC (Figure 7.4). AP Microeconomics – Chapter 7 Outline Average total cost is depicted as a U‐shaped curve, above AVC. The difference between ATC and AVC is AFC. C. Marginal cost is the additional cost of producing one more unit of output (MC = change in TC/change in Q). In Table 7.2, the production of the first unit raises the total cost from $100 to $190, so the marginal cost is $90. 1. Marginal cost can also be calculated as MC = change in TVC/change in Q. 2. Marginal decisions are very important in determining profit levels, because marginal revenue and marginal cost are compared to determine profit‐ maximizing output. 3. Marginal cost is a reflection of marginal product and diminishing returns. Marginal cost first falls sharply during increasing returns; when diminishing returns begin, the marginal cost will begin its rise (Figure 7.6). AP Microeconomics – Chapter 7 Outline 4. The marginal cost is related to AVC and ATC. These average costs will fall as long as the marginal cost is less than either average cost. As soon as the marginal cost rises above the average, the average will begin to rise. Students can think of their grade point averages, with the total GPA reflecting their performance over their years in school, and their marginal grade as their performance in Economics class this semester. If their overall GPA is a 3.0, and this semester they earn a 4.0 in Economics, their overall average will rise, but not as high as the marginal rate from this semester. D. Cost curves will shift if the resource prices change or if technology or efficiency change. It is important to make the distinction between the effects of changes in fixed and variable costs. 1. If a fixed cost increases (for example, the annual cost of an operating license or property taxes), the average fixed cost and average total cost increase, but the average variable cost and marginal cost do not change. 2. If a variable cost increases (for example, wages or materials), the average variable cost, marginal cost, and average total cost increase, but the average fixed cost does not change. V. Long‐Run Production Costs AP Microeconomics – Chapter 7 Outline A. In the long run, all production costs are variable (plant and industry size can expand or contract). B. Figure 7.7 illustrates different short‐run cost curves for five different plant sizes. D. The long‐run ATC curve shows the lowest per‐unit cost at which any output can be produced after the firm has had time to make all appropriate adjustments in its plant size (Key Graph Figure 7.8). D. Economies or diseconomies of scale exist in the long run. 1. Economies of scale explain the downward sloping part of the long‐run ATC curve; as plant size increases, long‐run ATC decreases. Labor and managerial specialization, the more efficient use of capital, and the spread of start‐up costs AP Microeconomics – Chapter 7 Outline over a larger amount of output as plant size expands all contribute to economies of scale. 2. Diseconomies of scale may occur if a firm becomes too large, as illustrated by the rising part of the long‐run ATC curve. For example, if a 10 percent increase in all resources result in a 5 percent increase in output, ATC will increase. Some reasons for this include distant management, worker alienation, and problems with communication and coordination. 3. Constant returns to scale will occur when ATC is constant over a variety of plant sizes. AP Microeconomics – Chapter 7 Outline E. Both economies of scale and diseconomies of scale can be demonstrated in the real world. Larger corporations at first may be successful in lowering costs and realizing economies of scale. To keep from experiencing diseconomies of scale, they may decentralize decision making by utilizing smaller production units. F. The concept of minimum efficient scale defines the smallest level of output at which a firm can minimize its average costs in the long run. 1. The firms in some industries realize this at a small plant size, such as apparel, food processing, furniture, wood products, snowboarding, and small‐appliance industries. 2. In other industries, in order to take full advantage of economies of scale, firms must produce with very large facilities that allow the firms to spread costs over an extended range of output. Examples include automobiles, aluminum, steel, and other heavy industries. This pattern also is found in several new information technology industries. VI. Applications and Illustrations A. Recent increases in gasoline prices affect firms that use gasoline as part of their production and distribution process. The increases in ATC, AVC, and MC will be more significant for firms like FedEx because of the need for gas for delivery vans, but the increases will have less impact on a firm like Symantec, which downloads its product to consumers via the Internet. B. A number of start‐up firms, such as Starbucks and Microsoft, have been able to take advantage of economies of scale by spreading product development and advertising costs over larger and larger units of output and by using greater specialization of labor, management, and capital. C. In 1996, Verson (a firm located in Chicago) introduced a stamping machine the size of a house, weighing as much as 12 locomotives. This $30 million machine enables automakers to produce in 5 minutes what once took 8 hours to produce. D. Newspapers in recent years are being forced out of business, as consumers opt to cancel their newspaper subscriptions and instead rely on the Internet for news. As newspapers are forced to spread their fixed costs over fewer newspapers, they must raise their prices, driving away even more customers. E. The aircraft assembly and ready‐mixed concrete industries provide extreme examples of differing MESs. Economies of scale are extensive in manufacturing airplanes, especially large commercial aircraft. As a result, there are only two large plants in the United States that manufacture large commercial aircraft. The concrete industry exhausts its economies of scale rapidly, resulting in thousands of firms in that industry. VII. LAST WORD: Don’t Cry over Sunk Costs A. Sunk costs are irrelevant in decision‐making. 1. The old saying “Don’t cry over spilt milk” sends the message that if there is nothing you can do about it, forget about it. AP Microeconomics – Chapter 7 Outline 2. Economic analysis says that you should not take actions for which marginal cost exceeds marginal benefit. 3. Suppose you have purchased an expensive ticket to a football game and you are sick the day of the game; the price of the ticket should not affect your decision to attend. B. In making a new decision, you should ignore all costs that are not affected by the decision. 1. A prior bad decision should not dictate a second decision for which the marginal benefit is less than marginal cost. 2. Suppose a firm spends $1 million on R&D only to discover that the product sells very poorly. The loss cannot be recovered by losing still more money in continued production. 3. If a cost has been incurred and cannot be partly or fully recouped by some other choice, a rational consumer or firm should ignore it. 4. Sunk costs are irrelevant! Don’t cry over spilt milk or sunk costs!