Promoting Good Quality Care Through Teamwork And Effective

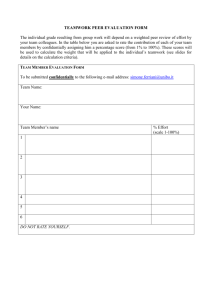

advertisement