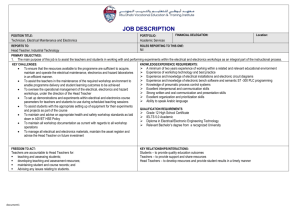

Corporate social responsibility in the global

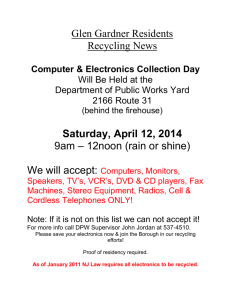

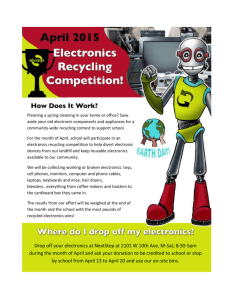

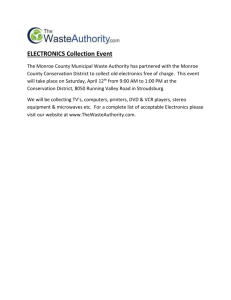

advertisement