1 A Late Modern Contract Law

advertisement

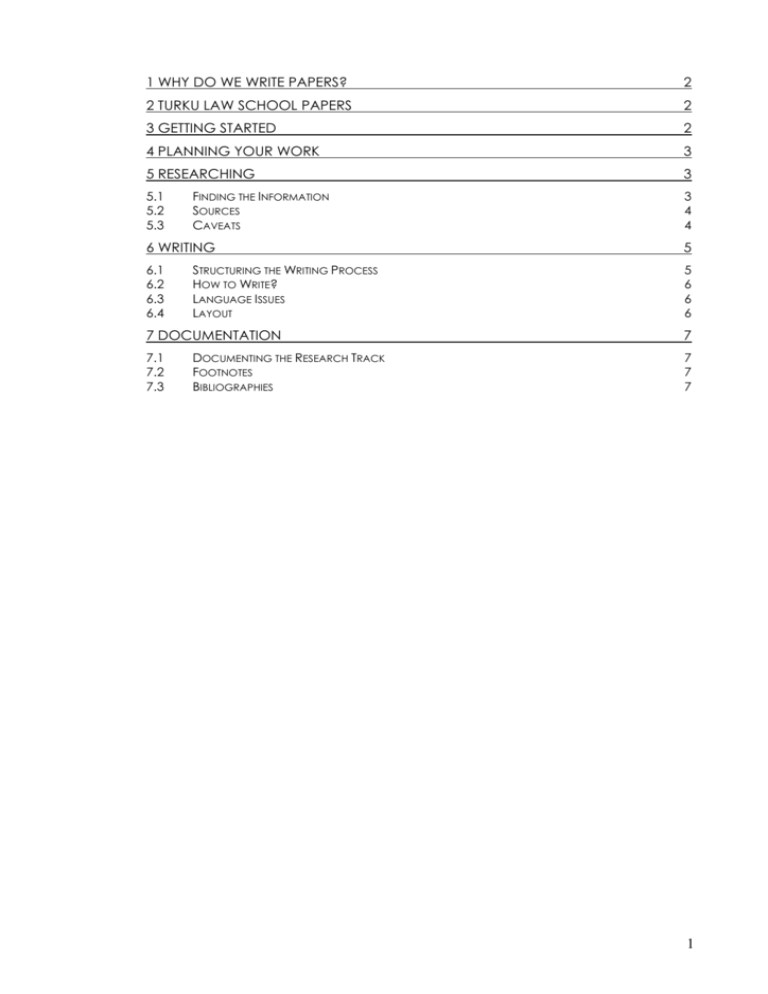

1 WHY DO WE WRITE PAPERS? 2 2 TURKU LAW SCHOOL PAPERS 2 3 GETTING STARTED 2 4 PLANNING YOUR WORK 3 5 RESEARCHING 3 5.1 5.2 5.3 3 4 4 FINDING THE INFORMATION SOURCES CAVEATS 6 WRITING 5 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 5 6 6 6 STRUCTURING THE WRITING PROCESS HOW TO WRITE? LANGUAGE ISSUES LAYOUT 7 DOCUMENTATION 7 7.1 7.2 7.3 7 7 7 DOCUMENTING THE RESEARCH TRACK FOOTNOTES BIBLIOGRAPHIES 1 1 Why Do We Write Papers? Do we write papers because we just happen to write papers? Is paper only a paper? Is it only an end in itself? Or is there some tacit purpose to writing papers? To a degree, the answer to the three first questions must be in the affirmative. We write papers because we write papers, because we have always been writing papers. Or at least I think we have. Writing a paper has been the modus vivendi of the academic world for a long time. Generations after generations of students have drafted little pieces of research, called them papers, and submitted them to be graded and criticised. In Finnish undergraduate and graduate law curricula, course papers have the task of preparing the student to draft a master’s thesis, a feast usually taking place during the fifth year of the student’s studies. The master’s thesis should be a 70 to 100 pages report on an independent research task. In the thesis the student is required to demonstrate that he or she is sufficiently read, knows the methods of his or her particular discipline, is proficient at research methods, able to frame a research problem and put together a convincing argument to support his or her view. Simultaneously, a master’s thesis is a useful indicator in deciding whether the student has acquired the skills needed in the professional world. In the course of undergraduate and graduate law studies, the student is usually required to write five to ten papers. These papers range from 3 to 4 page comments on case law to research papers of more than 30 pages in length. As the purpose of writing a paper is to prepare the student so that he or she is able to handle the future writing process of the master’s thesis, the paper should be as close to a miniature master’s thesis as possible. Thus, the paper should reflect independent research and thinking, display knowledge of standard legal research methods and argumentational patterns. If the paper fails to aid in meeting these requirements, it does not fulfil its purposes. 2 Turku Law School Papers In certain TLS courses, the students are also required to write papers. The requirements as to the length of the paper may vary, but whatever the particular task given to you, you should bear mind the general objectives set for papers. The goal is the master’s thesis and the papers written in the course should prepare you to write better papers, and ultimately a thesis. There are two issues to which one should pay close attention while writing a paper. First, thorough research is essential. Most of the days spent writing a paper should be spent in the library. The process should commence and end there. You should read what authorities have written on your topic and use the material to put together your own arguments. Second, independent thinking is a vital part of the writing process. Although it is often said that copying from one source adds up to a copyright infringement and an act of plagiarism, but copying from two sources produces a scholarly study, a good paper involves a good deal of independent thinking and sound scepticism of past studies and authorities. The emphasis on independent thinking has a twofold orientation. One, you should be able to frame your research problem independently and creatively. Ideally, you should be able to structure a problem that is both novel to the genre in which you operate and worthwhile to pursue. Second, you should be critical and display a fair dose of suspicion in relation to established authorities. Do not believe everything you read. 3 Getting Started Starting is always difficult. It often involves anxiety attacks, sudden feelings of compulsion to wash all the dishes in the house, and disproportionate interest in reality-TV series. All these are common phenomena. To avoid them you need objectives and deadlines and some determination. Remember that the first few hours are often crucial. After you have received your topic, please, go down to the library and see what is available. 2 Grab a few textbooks and see what has been written on the topic. But read first, write second. You desperately need to acquire a preliminary conception of the topic and its surroundings, and the only method of doing that is reading. 4 Planning Your Work With a couple of textbooks in your hand, you may start in earnest. It is time to plan your work. First of all, however, you need to do some research. See what literature references are offered in the material you have at your hands. Find those sources. Read them. This should take from a few hours to few days. Once you know the surroundings of the topic and have some kind of idea of what you will discuss in the paper, start planning the paper. Here, the approaches may differ; I have three in my mind, but there are more. Some people, plain and simple, sit down to a computer and start putting together a table of contents. This approach is feasible if you know the topic forehand and it is relatively simple and tractable. Examples of such topics could be e.g. a single provision or a group of provisions in a statute, or a line of cases that pursued in the source material. Some of us use a technique called mind mapping. Mind mapping is based on the flow of associations that topic sets free. In it, you take a sheet of paper, write the topic in the middle of it, and start thinking. Whatever ideas you get, write them down. Once the sheet starts to get full of ideas, it is time to start tracking their connections by drawing lines that connect one idea to another, thus building chains of hierarchy and interdependency. Mind mapping is perhaps best when the topic is neither straightforward nor particularly clear in your mind: let’s say you want to discuss the impact of soft law on international public law, but find your loss at the sea of all the different notions and concepts. Using the mind mapping technique may prove useful in helping you to sketch out and organize your thoughts and ideas. The third possibility is the worst: do not write anything. Just juggle the ideas in your head for hours after hours. I use it. It causes you headache, grey hairs and sometimes an untimely death. Whatever your method, the result of the planning should be a table of contents. It provides the plan for your work. A table of contents for a paper discussing free trade could look like this: 1. Introduction and Limits of the Paper i. The basic notion of free trade ii. The limits of discussion: free trade as reflected in WTO structures and rules 2. Free Trade i. Framework ii. Connections to other ideas and ideologies iii. Counter-ideologies 3. WTO Structures and Rules i. The basic structure of WTO ii. The Ideologies of WTO 4. A Concrete Body of Rules Analysed i. The rules ii. Their interpretation iii. Connection to the notion of free trade 5. Conclusions 5 Researching 5.1 Finding the Information Research is elemental. It should always be your first priority. A lawyer lives of information. Research could be characterized a three-phase process. First, you have to find your 3 way to the information, and, second, chump it up, and, then, third, digest it. None of the phases is a particularly easy job. And getting started could prove the hardest. Where to find something to read? Again, there are no clear rules, only suggestions. I suggest you start with the library downstairs 1 . Pick up the basic textbooks on the subject, if you can find them: they are not always readily available. After a few books and different expositions of the same problem, you’ll have some basic knowledge on the topic, and may pursue more advanced readings. Sometimes the basic textbooks contain footnotes that guide you to additional titles on the subject; sometimes you may consult recommended readings lists in the textbooks; or spend time on the computers at the library. 5.2 Sources The traditional lawyer relies on three types of sources: treatises, articles, and official publications. Treatises, books that is, may be the hardest to find. However, because of the sheer scope of the volumes, they provide the most information in a readily available form and manner. In addition to often treating the current problem in exhausting detail, the authors usually place it in its broader framework. Thus, for thorough expositions of problems, rely on treatises, if you can find some. For details, you must, however, often turn to articles. Many of the more minor problems are sorted out there. Articles, however, may sometimes prove difficult to read as the authors often assume that the reader is familiar with the basics of the subject at hand. Thus, you should read articles first when you have some kind of conception of your topic. Official publications, such as statutes, government bills, travaux preparatoires, and case law, whatever their place in the hierarchy of sources of law, are at times the most important sources of material, in particular if your subject requires adopting a dogmatic research method. 5.3 Caveats Research is tedious work and hard on your buttocks. It should, however, be done. First, as a general rule, I would say that you should start writing first when you think you have read three times too much. On the other hand, I suggest you spend three times as much time reading as you do writing. For the most of us, this, of course, is not possible. We either do not have the nerves, the motivation, or the necessary anatomic structure. We want to accomplish something substantial, get some words on the paper, not just spend time hovering over a book. Reading is not easy, and there are no foolproof tricks to make it less nerve cracking. But whatever you do, remember that you cannot escape reading. However important reading is it is not enough. There are three caveats. First, you should understand what you are reading. Some texts open with lesser scrutiny; some require the whole of your attention. Some books you may just flick through, with some, you have to sit down and trace the argumentation with care, slowly and painstakingly. Second, one must be critical while reading. This is especially true of internet sources, which you should treat with uttermost caution, if not suspicion. Do not trust everything you read. The availability of books is often a problem. The collections are limited in scope and English language resources are usually few and hard to find as they are seldom located on the shelves. Mastering the library and its collections is a discipline in itself. In addition to the law school library, you may use the other university and public libraries in the Turku region. In addition to the library downstairs, the best guesses are the Åbo Akademi library and the TuKKK (Turku School of Economics and Business Administration) library, as they carry the second largest and versatile collections of law volumes in the region. If you travel to Helsinki, the local law faculty library and the Library of the Parliament are good places to pay a visit. Collection data of all the scientific libraries in Finland are available online. In the libraries, do not hesitate to contact the staff: they are there to help you. Do not forget the web either. In addition to plain old-fashioned googleing, you can access a number of journals online at different databases and services. The University Library carries a number of services accessible at http://kirjasto.utu.fi/e-lukusali. Another outstanding service is http://westlaw.com, to which the faculty has user rights. Westlaw carries all US law review and journal articles starting from 1982, and thus, could be characterised as a marvel. Contact Mr. Viljanen or Mr. Wacklin (the faculty information specialist) for the password and on how to use the Westlaw. 1 4 Major publishers and law journals are safe guesses as far as reliability is concerned: the texts are peer reviewed and edited prior to publication, thus ridding the world of the worst text submitted for publication. Even established authorities may be useless under certain circumstances. A 1990 textbook may have been rendered useless and obsolete because of a law reform. Thus, be careful when you read. Think. Thirdly, you should always take notes, i.e. write things down as you read. Whatever ideas you manage to develop should be written them down in sufficient detail. Otherwise, they are gone in five minutes and seldom come back. 6 Writing 6.1 Structuring the Writing Process Writing a paper is often a lengthy process, a winding road with its uphills and downhills. It seldom goes as planned, and you should not expect it to do so. Prepare for little sleep, deadlines that are not met and frustration. It could be useful to divide the writing process to three phases. The first phase should take a day or two, a week at the longest. During it you get to know your topic, situate it into the broader framework of things, acquire a preliminary feel for the subject, and produce the first of your work plans and table of contents of the future paper. This first phase should be followed by one or two weeks of research 2 . As in the first phase, spend your time at the library, read books, find articles, make notes and think. Above, I have emphasized research. Research is elemental, and the notes you have produced during research often, if existing, provide a good starting point for your writing. You may be able to use them as the body of your text. Thus, making notes is worthwhile. As you do research, you should also work on your plan of work and update the table of contents once you have new ideas or stumble on previously unknown problems. At the end of this phase, you should have the necessary material collected and read, and a healthy collection of notes on different issues related to the subject matter of the study. The next phase involves both research and writing. In it you will draft the bulk of your paper, left largely alone with your thoughts and problems. The notes that you have taken hopefully provide you with a starting point. Expand on the table of contents: place the notes into their places under the headings, if you have not already done so. Write more text under the headings. Read more on the topics you find most interesting or central in relation to your topic. During this phase, there are individual differences. Some work meticulously and logicly, finishing one chapter before starting a new one. Some may prefer less organized working habits, writing a sentence there and a sentence. I would prefer to stay organized, but seldom find myself able to concentrate for more than three minutes on one theme. So, I write chaotically. Writing a bigger paper may seem a colossal task. However smart you are, you cannot do it in two days, let alone during the last night. Instead, you need to work patiently and meticulously. Set your self objectives and deadlines. “I’ll write this passage before two o’clock”. “Today, I’ll write 800 words.” If you fail to attain your goals, you fail. No big deal. There are better days and there are worse days. Try not to leave everything to the frenzied efforts of the last days and nights. Do not expect to write more that 3 pages on a good day: miracles seldom occur. The fourth phase of writing consists of fine tuning your argumentation and proofreading. Even though it often is considered a trivial task and boring ad infinitum, it is essential. To make your paper easy to read, and, thus, attractive, put some effort in to proofreading. Whatever you do, remember to concentrate on your work. Do not succumb to the temptations of Freecell or Minesweeper. Take breaks if you start to feel like surfing or playing games. 2 5 6.2 How to Write? The Anglophone culture sets an emphasis on concise and unambiguous writing. Within this tradition, argumentation is both straight-forward and goal-oriented. Instead of concentrating on showing a brilliance of intellect or a flair for expressive or allusive writing, the English language standards condition the writer to pursue an intellectual path that starts at place A and ends at place B. A claim is first made or a question is posed. In the following paragraphs, the claim is either justified or denounced, or the question is answered. As we write in English, we should adopt and adapt to the convention common to the Anglophone world. Thus, in the beginning of each paragraph you should make a claim. In the sentences that follow it, you should give reasons for your claim. A proficient student also tries to predict the counterarguments and answer to them before they are raised. The Germanic trait of starting with motivations and reason, thus working to the answer, is not particularly encourages. The style is, however, free. Just make your case. Rewriting and rethinking are both important. Writing is not easy and rarely comes naturally: you need to work on your texts. That usually brings about a ruthless and brutal rewriting. Do not feel content with first versions: pity is for the weak. Be critical. The introductory passage on the archaic development of some branch of law written 2.30 a.m. the first day may be totally unnecessary and useless, or at least in need of rewriting. 6.3 Language Issues The TLS papers are written in English. The English language is a challenge for most, a handicap that we must overcome. It is never easy to write, let alone in a foreign language, of which we may have a less than perfect command. In ITL we do not expect you to write flawless English, nor do we expect you to demonstrate flair and elegance or feel for nuances and miniscule differences. We simply expect you to write intelligible English. As much as being a nuisance, the fact that we are writing in a foreign language, may be also beneficial. It compels us to keep things simple, a trait often lacking in academic writing. We write to be read, and we write to be understood. We should not write just to demonstrate our intelligence, wit, acrobatic verbal skills, or command over allusive and ambiguous language. Instead, we should state our case as frankly as possible, make it easily intelligible but simultaneously appealing to the reader. Within the confines of this short manual, I cannot go into details on practical language, nor do I feel particularly competent in doing so. If you feel unsure, consult a grammar book or a dictionary. 6.4 Layout The paper should look good and should be written in type. The layout – although arguably a superficial factor – constitutes an important part of the paper. Appearances count. If you look professional, you are often treated as a professional, whatever your merits or credentials. However, I should stress, the appearances do not affect the grading of your paper. It is, nevertheless, useful to pay attention the visual side things. How to look professional? Make the paper look like it was printed in a printing house. The font size should be at least 12 points and the spacing 1,5 lines. Use a readable link. Times New Roman is the traditional choice. Those who feel adventurous may try e.g. Garamond, Arial or Palatino. Justify both sides of the text. Each paragraph should be followed by a 12 point divide. Do not indent the first line of each paragraph. Use numbered headings and page numbers. This paper can be used as an example of a layout, with certain exceptions (spacing, indentation, and paragraph divides). The paper should contain: (1) a title page specifying the title of the paper, the author’s name, the university at which it was written, name of the course, and the date of submission; (2) a table of contents; (3) a bibliography; 6 (4) the body text; (5) footnotes and other references. The bibliography should contain information on each of the sources. The information should be such that the source can be easily found. 7 Documentation 7.1 Documenting the Research Track Documenting the research track is elemental in jurisprudential studies. In most law treatises, a considerable amount of space is taken up by footnotes. They contain both source references and explanatory notes. This is due to the nature of legal research. Law is a normative discipline that builds on the authority of the past. Thus, in order to argue convincingly, you must use the past to expose the present and the future, and the past must not be fictitious but verifiable. So, tell us where you got the information from. The line between infringing copyrights and writing a scholarly is sometimes fine. You often describe in length what an authority has written. Such descriptions tend to closely resemble the original expositions. Even though, it is completely acceptable and common practice to recite other’s text, it should never be done word to word. At the very least rephrase, but preferably comment the text that you use and bring your own point of view. If you want to cite, use citation marks or indent the citation, and designate the source. 7.2 Footnotes In jurisprudential texts footnotes often contain bibliographical references and short explanatory comments and excursa that the author has not deemed worthy of being included in the body text. In other disciplines, the same function is occupied by e.g. intertextual references or endnotes. In jurisprudence, footnotes are the standard, but if you are accustomed to using e.g. endnotes, you are free to do so, provided that you are consistent. Recent decades have seen the reduction of the amount of text included in the footnotes, thus footnotes are increasingly becoming methods to indicate the sources where the information was derived from. In student papers, the primary function of the footnote is to contain a reference to source. As such, footnotes often tend to be quite laconic, containing only few words in addition to the references. A basic footnote that indicates that the information contained in this paragraph derives from page 199 in Aarnio 1988, is next 3 . If you wish to imply that the informational contents of one single sentence derive from one source, do by placing the footnote prior to the colon in that sentence 4 . A footnote placed in the end of a paragraph located after the final colon usually implies that the information in the whole paragraph derives from one source. 5 Please keep the footnotes short. Under certain conditions it is useful to add explanatory comments on the sources in the footnotes, but in student papers this should be a rare phenomenon. 7.3 Bibliographies Your paper must have a bibliography. A separate bibliography, although often lacking in Anglophone treatises, makes things easier for everybody. No more searches for untraceable references to op. cit. supra, but a clear and unambiguous reference to a source that can be looked up in the bibliography. You should provide enough information on the titles you refer to in the bibliography. The data that you need to specify varies depending on the type of source material and the culture the writer comes. Articles, treatises, and official material are reported differently. See Aarnio 1988, 199. The page number may be designated by the abbreviation p.. See Aarnio 1998, 199. 5 See Aarnio 1998, 199. Thus, this would designate that the informational contents derive from Aarnio. 3 4 7 In ITL and on TLS courses, I suggest you comply with the following rules. On books, you should specify the following data: 1. the author; 2. the title; 3. the domicile of the publisher; 4. the publisher; 5. the year the book was published and; 6 6. a shorthand reference. Thus, a basic entry for a book looks like this: Bauman, Zygmunt 7 , Intimations of Postmodernity. 8 London, New York 9 : Routledge 10 , 1992. (Bauman 1992) 11 A title with two authors: Deleuze, Gilles & Guattari, Félix12, A Thousand Plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London: The Athlone Press, 1983. (Deleuze & Guattari 1983) A title compiled of separate articles and edited: Benson, Peter (ed.) Philosophy and Contract Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. (Scanlon 2000) On articles published journals are reviews you should specify the following data: 1. the author; 2. the title of the article; 3. the volume of the journal; 4. the name of the journal; 5. the year the article was published and in parentheses and; 6. the pages on which the article appeared. A basic entry should thus look the following: Anderson, John L, ”Techniques” for Governance. 35 The Social Sciences Journal (1998), 493-508. (Anderson 1998) On articles published in edited books you should specify the following data: 1. the author; 2. the title of the article; 3. the bibliographic data on the book; 4. the pages on which the article appeared. If the title is a reprint or a translation and the date of the original printing is much earlier than the date of the current edition you should specify also the year the work was first published. For example Smith, Adam, An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976 [1776]. Thus, the year of original printing should be specified in brackets following the date of current printing. 7 Last name and first names, separated by a comma in normal font. 8 Title in italics, separated by a comma from the author and a colon, from the publisher’s domicile. 9 Domiciles (if multiple) separated by a comma. 10 The publisher’s name in the form specified on the title page. 11 It is useful to use a hanging indentation in bibliographies. 12 The authors separated by a & sign. 6 8 A basic entry should thus look like the following: Ewald, Francois, Vakuutusyhteiskunta in Eräsaari, Risto & Rahkonen, Keijo, Hyvinvointivaltion tragedia. Helsinki: Gaudeamus, 1995, 1-28. (Ewald 1995) A bibliography could thus look like the following: Baker, Wayne & Jimerson, Jason B. The Sociology of Money. 35 American Behavioral Scientist (1992), 678-693. (Baker & Jimerson 1992) Barnes, David W. The Anatomy of Contract Damages and Efficient Breach Theory. Southern California Interdisciplinary Law Journal (1998). (Barnes 1998) Barry, Andrew, The Anti-Political Economy. 31 Economy and Society (2002), 268284. (Barry 2002) Baudrillard, Jean, Symbolic Death and Exchange. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: Sage Publigations, 1993. (Baudrillard 1993) Good luck. 9