HAMLET Study Guide - Hawaii Theatre Center

advertisement

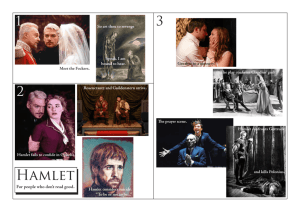

-- The Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series HAMLET presentsWilliam Shakespeare’s Starring the Hawaii Theatre Young Actors Ensemble Original soundscape composed and performed by Dylan Pilger 6th – 12th grade STUDY GUIDE April 24, 25, 26 The Hawaii Theatre This production is made possible in part through generous support from ABC Stores, Bank of Hawaii Foundation, The Bretzlaff Foundation, Samuel N. and Mary Castle Foundation, The City and County of Honolulu, Friends of Hawaii Charities, G. N. Wilcox Trust, Thomas J. Long Foundation, Macy’s, McInerny Foundation, RM Towill Foundation, State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, through appropriations from the Legislature of the State of Hawaii and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. :: Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre Welcome! Dear Teacher, We are thrilled you are bringing your students to the Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee production of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, featuring the talented members of this year’s Hawaii Theatre Young Actors Ensemble. Please feel free to copy and share this Study Guide with other teachers. It will be helpful to cover some of the content before the performance, specifically the synopsis, the characters, and the concept of this particular production. Some content is more appropriate for classroom discussion after you and your students have experienced our Hamlet firsthand. However you choose to use it, our intention with this Study Guide is to help you and your students get as much as possible from your upcoming adventure at the Hawaii Theatre. Eden-Lee Murray Education Director The Hawaii Theatre Center 1 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Elsinore Castle, Courtesy of Flickriver Table of Contents: Welcome! ……………………………………………………………………………………….1 Table of Contents……………………………………………………………………………….2 Preparing for Your Hawaii Theatre Adventure…………………...…………..…………….4 About HTC Education Program Theatre Classes…………………………………….……..6 Pre-Show Classroom Prep Notes from the Director……….………………………………………………………..7 Key Facts……………………………………………………………………………….8 Historical Context for the Story……………………………………………...………..10 Who’s Who in Hamlet: Meet the Characters…………………………………………11 What Happens in Hamlet? Plot Overview………….....................................................13 Themes, Motifs and Symbols in Hamlet………………………………………………15 Pre-show Discussion Questions………………………………………………………..18 Hamlet Trivia Famous Quotes from Hamlet……………….…………………………………………19 What was a Castle?……………………….…………………………………………...20 Famous Hamlets Over the Years………….…………………………………..………22 2 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Some Context for the Plays: Shakespeare’s Audience………………………..…...……………………………...….26 How to Listen to Shakespeare…………..….…………………………………………..28 Playing Shakespeare………………..………………….…………………………….…29 Shakespearean Insults…………………………..………………………………………34 About William Shakespeare…………………...………..………………………………36 Shakespeare’s Theatre…………...…….………………………………………………..39 Meet Our Players………………..…………………………………………………………….42 The Production Team……………….………………………………………………………...43 Afterglow: Reinforcing the Experience--Post-show Classroom Discussion & Activities 6th – 8th Grade…………………………………………………………………………..44 9th – 12th Grade…………………………………………………………………………46 Student Evaluation……………………………………………………………………………49 Teacher Evaluation………………………………………………………………………..….50 Credits……………………………………………………………………………………..….51 3 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Preparing for Your Hawaii Theatre Adventure Before . Read Hamlet by William Shakespeare with your students, if at all possible. At the very least, go over the plot summary, character descriptions and section on themes in this Study Guide—the section on Pre-Show Classroom Prep, beginning on page . Lead pre-show discussions with your class about the characters and circumstances of the play The Day of the Play Please plan on getting to the Theatre at least 30 minutes before the performance. When you arrive, the ushers will take you to your places. Before the show, our ensemble of Elizabethan Players and Roustabouts will be in the auditorium, mingling and improvising with the audience, offering information about themselves (in character), and the role(s) they will portray in the play. This kind of preshow exchange offers a special opportunity for students to connect with those who are about to perform for them. No food or drink is allowed in the theatre. Lunch bags can be left in the lobby. Theatre Etiquette Before coming to the theatre, it would be helpful to speak with your students about how live performance differs from going to the movies or watching TV. Something for the students to keep in mind is that the Hamlet performers they are watching are their peers—our Hawaii Young Actors Ensemble players are all high school age. Please insist that your students be respectful of these young players who have worked so hard (since September!) to bring this play to you. Remind them that during a live performance, the actors onstage can both see and hear the audience. Talking and making loud comments will not only distract the performers, but will also compromise the experience for others in the audience as well. Students should not leave their seats except to use the restroom. Cell phones must be silenced; texting and electronic games are not permitted. Photographs may not be taken. Any students disrupting the performance will be asked to leave the theatre and wait in the lobby with a teacher or chaperone. 4 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Restrooms Restrooms are located at either end of the lobbies on the first and second floors of the Theatre. It’s a good idea to use the restroom before the performance. If anyone needs to use the restroom during the performance, they should walk quietly up either aisle and out into the lobby. Leaving the Theatre After the performance, please keep students sitting quietly in their seats. We have a special “bus game” that insures a safe and orderly exit with the assistance of House Management and our trained volunteer ushers. After the Play Debrief your students and share the post-show activities provided in this Study Guide. Feel free to create your own post-show questions/activities inspired by the performance. Feedback Your feedback is important to us! In order to improve our programming, we appreciate any feedback you and your students can provide. Please fill out the teacher evaluation forms and have the students share their reactions in the student form provided. Then either email them to eden-leemurray@hawaiitheatre.com or fax them to 528-0481. 5 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide HTC Education Program Theatre Classes Hawaii Theatre Young Actors Ensemble is a company of high school age students from across O`ahu who meet twice a week after school to learn acting, voice and movement technique; and to rehearse and perform classical theatre. In the spring, HTYAE performs Student Matinees and public performances of a full Shakespeare production onstage at the Hawaii Theatre. Next year’s play will be the rollicking comedy, Much Ado About Nothing. NOTE: This is a pre-professional training program led by HTC Education Director and Po‘okela Awardwinning actress Eden-Lee Murray, with Master Classes from top local theatre professionals. It is NOT a drama club! AUDITIONS: Onstage at the Hawaii Theatre. You must call to register—791-1397. This year’s auditions will be held on Mon., June 10; and Mon., August 12. COST Participation in HTYAE costs $250 per semester, with need-based scholarships available. Students will advance to work on the Shakespeare production in the second semester by invitation, based on the work and attitude they demonstrate during the first 3 months of the program. Hawaii Theatre Junior Ensemble A program designed for O`ahu middle schoolers, age 10 – 12. This is an introductory acting program led by HTC Education Director Eden-Lee Murray. It focuses on improvisation and basic acting techniques, with an emphasis on creative collaboration as well as performance skills. Classes take place once a week, after school 4-5:30pm, from September through May. No prior acting experience required. Cost for the Sept. – May program is $250. The Junior Ensemble is a feeder program for the Hawaii Theatre Young Actors’ Ensemble. _______________________________________ HTYAE Technical Apprenticeship Program The Apprenticeship Program was created as a way for teens interested in technical theatre to be individually mentored in those skills, to experience life behind the scenes of a large professional theatre, and to give high school students marketable skills as electricians, carpenters, set/light/costume designers, stage managers, and production assistants. Those who wish to participate must call to register for an interview. For more information call 791-1397, or email eden-leemurray@hawaiitheatre.com 6 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Pre-Show Classroom Prep Notes from the Director One of the joys of working with Shakespeare is the huge latitude for interpretation. Our goal with this production is to transport our audiences back to the Elizabethan era, when roving bands of rough and tumble players toured Shakespeare’s plays throughout the countryside, making use of whatever they found in city squares and other public spaces to serve as stages for their performances. Shakespeare’s plays were originally performed with little if any scenery, on a bare stage in daylight. To inform an audience of location, he’d write lines like “Here we are in the Forest of Arden!” In that spirit, we’ll be running with a very spare, open set, comprised of rough, wooden platforms that will be reconfigured by our players to indicate change of location. In Shakespeare’s time, women were not allowed onstage, so any female roles had to be portrayed by boy actors, (one reason there are generally so few female roles in Shakespeare’s plays). To go along with this conceit, each of our HTYAE’ers has created his or her male Player. In turn, each Elizabethan player will portray one of the roles in Hamlet. This approach has given our young performers opportunities for much creative improvisation in rehearsals, as the company has had to create a collective past for itself, determine and define the relationships within the group, and figure out why each player has been assigned his role in Shakespeare’s most famous tragedy. Then, of course, each Elizabethan player has had to create and rehearse that role. Fun! Our Players will be setting up for the performance as their audiences enter the Theatre. Please let your students know the Players will be improvising with them in character, offering facts about themselves as actors, talking (bragging?) about the roles they’ll be playing, and in general, looking to create relationship before the story gets underway. One further note: Hamlet has five famous soliloquies in this play. Shakespeare’s original intention with soliloquies was for an actor to break the fourth wall and speak directly to the audience, either to tell them the back story behind a scene they’ve just watched, to share thoughts/feelings kept hidden from other characters, to let the audience in on what he intends to do next, or to think out loud and make a discovery right in front of them. Our Hamlet will be doing exactly that, and to help him connect with the audience, we’ll have a special lighting adjustment so that he can see everyone in the house and address individuals. He’ll be speaking to them, not at them. Enjoy! Eden-Lee Murray 7 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Key Facts Courtesy of: http://www.sparknotes.com/shakespeare/hamlet/context.html FULL TITLE AUTHOR · The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark · William Shakespeare · Play TYPE OF WORK GENRE · Tragedy, revenge tragedy LANGUAGE · English TIME AND PLACE WRITTEN · London, England, early seventeenth century (probably 1600–1602) · 1603, in a pirated quarto edition titled The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet; 1604 in a superior quarto edition DATE OF FIRST PUBLICATION PROTAGONIST · Hamlet · Hamlet feels a responsibility to avenge his father’s murder by his uncle Claudius, but Claudius is now the king and thus well protected. Moreover, Hamlet struggles with his doubts about whether he can trust the ghost and whether killing Claudius is the appropriate thing to do. MAJOR CONFLICT · The ghost appears to Hamlet and tells Hamlet to revenge his murder; Hamlet feigns madness to mask his intentions; Hamlet stages the mousetrap play; Hamlet passes up the opportunity to kill Claudius while he is praying. RISING ACTION · When Hamlet stabs Polonius through the arras in Act III, scene iv, he commits himself to overtly violent action and brings himself into unavoidable conflict with the king. Another possible climax comes at the end of Act IV, scene iv, when Hamlet resolves to commit himself fully to violent revenge. CLIMAX · Hamlet is sent to England to be killed; Hamlet returns to Denmark and confronts Laertes at Ophelia’s funeral; the fencing match; the deaths of the royal family FALLING ACTION SETTING (TIME) · The late medieval period, though the play’s chronological setting is notoriously imprecise SETTINGS (PLACE) · Denmark 8 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide FORESHADOWING TONE · The ghost, which is taken to foreshadow an ominous future for Denmark · Dark, ironic, melancholy, passionate, contemplative, desperate, violent · The impossibility of certainty; the complexity of action; the mystery of death; the nation as a diseased body THEMES · Incest and incestuous desire; ears and hearing; death and suicide; darkness and the supernatural; misogyny MOTIFS · The ghost (the spiritual consequences of death); Yorick’s skull (the physical consequences of death) SYMBOLS 9 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Historical Context http://www.sparknotes.com/shakespeare/hamlet/context.html Written during the first part of the seventeenth century (probably in 1600 or 1601), Hamlet was probably first performed in July 1602. It was first published in printed form in 1603 and appeared in an enlarged edition in 1604. As was common practice during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Shakespeare borrowed for his plays ideas and stories from earlier literary works. He could have taken the story of Hamlet from several possible sources, including a twelfth-century Latin history of Denmark compiled by Saxo Grammaticus and a prose work by the French writer François de Belleforest, entitled Histoires Tragiques. The raw material that Shakespeare appropriated in writing Hamlet is the story of a Danish prince whose uncle murders the prince’s father, marries his mother, and claims the throne. The prince pretends to be feeble-minded to throw his uncle off guard, then manages to kill his uncle in revenge. Shakespeare changed the emphasis of this story entirely, making his Hamlet a philosophically minded prince who delays taking action because his knowledge of his uncle’s crime is so uncertain. Shakespeare went far beyond making uncertainty a personal quirk of Hamlet’s, introducing a number of important ambiguities into the play that even the audience cannot resolve with certainty. For instance, whether Hamlet’s mother, Gertrude, shares in Claudius’s guilt; whether Hamlet continues to love Ophelia even as he spurns her, in Act III; whether Ophelia’s death is suicide or accident; whether the ghost offers reliable knowledge, or seeks to deceive and tempt Hamlet; and, perhaps most importantly, whether Hamlet would be morally justified in taking revenge on his uncle. Shakespeare makes it clear that the stakes riding on some of these questions are enormous—the actions of these characters bring disaster upon an entire kingdom. At the play’s end it is not even clear whether justice has been achieved. 10 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Who’s Who in Hamlet: Meet the Characters Courtesy of: http://www.sparknotes.com/shakespeare/hamlet/context.html Hamlet - The Prince of Denmark, the title character, and the protagonist. About thirty years old at the start of the play, Hamlet is the son of Queen Gertrude and the late King Hamlet, and the nephew of the present king, Claudius. Hamlet is melancholy, bitter, and cynical, full of hatred for his uncle’s scheming and disgust for his mother’s sexuality. A reflective and thoughtful young man who has studied at the University of Wittenberg, Hamlet is often indecisive and hesitant, but at other times prone to rash and impulsive acts. He also possesses an extraordinary wit, and flashes of a lively sense of humor appear throughout the play, despite his desperate circumstances. Claudius - The King of Denmark, Hamlet’s uncle, and the play’s antagonist. The villain of the play, Claudius is a calculating, ambitious politician, driven by his sexual appetites and his lust for power, but he occasionally shows signs of guilt and human feeling—his love for Gertrude, for instance, seems sincere. Gertrude - The Queen of Denmark, Hamlet’s mother, recently married to Claudius. Gertrude loves Hamlet deeply, but she is a shallow, weak woman who seeks affection and status more urgently than moral rectitude or truth. Polonius - The Lord Chamberlain of Claudius’s court, a pompous, conniving old man. Polonius is the father of Laertes and Ophelia. Horatio - Hamlet’s close friend, who studied with the prince at the University of Wittenberg. Horatio is loyal and helpful to Hamlet throughout the play. After Hamlet’s death, Horatio remains alive to tell Hamlet’s story. Ophelia - Polonius’s daughter, a beautiful young woman with whom Hamlet has been in love. Ophelia is a sweet and innocent young girl, who obeys her father and her brother, Laertes. Dependent on men to tell her how to behave, she gives in to Polonius’s schemes to spy on Hamlet. Even in her lapse into madness and death, she remains maidenly, singing songs about flowers and finally drowning in the river amid the flower garlands she had gathered. Laertes - Polonius’s son and Ophelia’s brother, a young man who spends much of the play in France. Passionate and quick to action, Laertes is clearly a foil for the reflective Hamlet. Fortinbras - The young Prince of Norway, whose father the king (also named Fortinbras) was killed by Hamlet’s father (also named Hamlet). Now Fortinbras wishes to attack Denmark to avenge his father’s honor, making him another foil for Prince Hamlet. 11 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide The Ghost - The specter of Hamlet’s recently deceased father. The ghost, who claims to have been murdered by Claudius, calls upon Hamlet to avenge him. However, it is not entirely certain whether the ghost is what it appears to be, or whether it is something else. Hamlet speculates that the ghost might be a devil sent to deceive him and tempt him into murder, and the question of what the ghost is or where it comes from is never definitively resolved. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern - Two slightly bumbling courtiers, former friends of Hamlet from Wittenberg, who are summoned by Claudius and Gertrude to discover the cause of Hamlet’s strange behavior. Osric - The foppish, foolish courtier who summons Hamlet to his duel with Laertes. Marcellus and Bernardo - The castle officers who first see the ghost walking the ramparts of Elsinore and who summon Horatio to witness it. Marcellus is present when Hamlet first encounters the ghost. Francisco - A soldier and guardsman at Elsinore. Chromolithograph illustration by Robert Dudley, published 1856-1858. Ann Ronan Picture Library. 12 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide What Happens in Hamlet? Plot Overview Courtesy of: http://www.sparknotes.com/shakespeare/hamlet/context.html On a dark winter night, a ghost walks the ramparts of Elsinore Castle in Denmark. Discovered first by a pair of watchmen, then by the scholar Horatio, the ghost resembles the recently deceased King Hamlet, whose brother Claudius has inherited the throne and married the king’s widow, Queen Gertrude. When Horatio and the watchmen bring Prince Hamlet, the son of Gertrude and the dead king, to see the ghost, it speaks to him, declaring ominously that it is indeed his father’s spirit, and that he was murdered by none other than Claudius. Ordering Hamlet to seek revenge on the man who usurped his throne and married his wife, the ghost disappears with the dawn. Prince Hamlet devotes himself to avenging his father’s death, but, because he is contemplative and thoughtful by nature, he delays, choosing to feign madness until he can decide what course of action to pursue. Claudius and Gertrude worry about the prince’s erratic behavior and attempt to discover its cause. They employ a pair of Hamlet’s friends, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, to watch him. When Polonius, the pompous Lord Chamberlain, suggests that Hamlet may be mad with love for his daughter, Ophelia, Claudius agrees to spy on Hamlet in conversation with the girl. But though Hamlet certainly seems mad, he does not seem to love Ophelia: he orders her to enter a nunnery and declares that he wishes to ban marriages. A group of traveling actors comes to Elsinore, and Hamlet seizes upon an idea to test his uncle’s guilt. He will have the players perform a new scene he writes for them, closely resembling the sequence by which Hamlet imagines his uncle to have murdered his father, so that if Claudius is guilty, he will surely react. When the moment of the murder arrives in the theater, Claudius leaps up and leaves the room. Hamlet and Horatio agree that this proves his guilt. Hamlet goes to kill Claudius but finds him praying. Since he believes that killing Claudius while in prayer would send Claudius’s soul to heaven, Hamlet considers that it would be an inadequate revenge and decides to wait. Claudius, now frightened of Hamlet’s madness and fearing for his own safety, orders that Hamlet be sent to England at once. 13 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Hamlet goes to confront his mother, in whose bedchamber Polonius has hidden behind a tapestry. Hearing a noise from behind the tapestry, Hamlet believes the king is hiding there. He draws his sword and stabs through the fabric, killing Polonius. For this crime, he is immediately dispatched to England with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. However, Claudius’s plan for Hamlet includes more than banishment, as he has given Rosencrantz and Guildenstern sealed orders for the King of England demanding that Hamlet be put to death. In the aftermath of her father’s death, Ophelia goes mad with grief and drowns in the river. Polonius’s son, Laertes, who has been staying in France, returns to Denmark in a rage. Claudius convinces him that Hamlet is to blame for his father’s and sister’s deaths. When Horatio and the king receive letters from Hamlet indicating that the prince has returned to Denmark after pirates attacked his ship en route to England, Claudius concocts a plan to use Laertes’ desire for revenge to secure Hamlet’s death. Laertes will fence with Hamlet in innocent sport, but Claudius will poison Laertes’ blade so that if he draws blood, Hamlet will die. As a backup plan, the king decides to poison a goblet of wine, which he will give Hamlet to drink should Hamlet score the first or second hits of the match. Hamlet returns to the vicinity of Elsinore just as Ophelia’s funeral is taking place. Stricken with grief, he attacks Laertes and declares that he had in fact always loved Ophelia. Back at the castle, he tells Horatio that he believes one must be prepared to die, since death can come at any moment. A foolish courtier named Osric arrives on Claudius’s orders to arrange the fencing match between Hamlet and Laertes. The sword-fighting begins. Hamlet scores the first hit, but declines to drink from the king’s proffered goblet. Instead, Gertrude takes a drink from it and is swiftly killed by the poison. Laertes succeeds in wounding Hamlet, though Hamlet does not die of the poison immediately. First, Laertes is cut by his own sword’s blade, and, after revealing to Hamlet that Claudius is responsible for the queen’s death, he dies from the blade’s poison. Hamlet then stabs Claudius through with the poisoned sword and forces him to drink down the rest of the poisoned wine. Claudius dies, and Hamlet dies immediately after achieving his revenge. At this moment, a Norwegian prince named Fortinbras, who has led an army to Denmark and attacked Poland earlier in the play, enters with ambassadors from England, who report that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are dead. Fortinbras is stunned by the gruesome sight of the entire royal family lying sprawled on the floor dead. He moves to take power of the kingdom. Horatio, fulfilling Hamlet’s last request, tells him Hamlet’s tragic story. Fortinbras orders that Hamlet be carried away in a manner befitting a fallen soldier. Lizzie Siddal as Ophelia, drawn by Millais 14 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Themes, Motifs and Symbols in Hamlet Themes Themes are the fundamental and often universal ideas explored in a literary work. The Impossibility of Certainty What separates Hamlet from other revenge plays (and maybe from every play written before it) is that the action we expect to see, particularly from Hamlet himself, is continually postponed while Hamlet tries to obtain more certain knowledge about what he is doing. This play poses many questions that other plays would simply take for granted. Can we have certain knowledge about ghosts? Is the ghost what it appears to be, or is it really a misleading fiend? Does the ghost have reliable knowledge about its own death, or is the ghost itself deluded? Moving to more earthly matters: How can we know for certain the facts about a crime that has no witnesses? Can Hamlet know the state of Claudius’s soul by watching his behavior? If so, can he know the facts of what Claudius did by observing the state of his soul? Can Claudius (or the audience) know the state of Hamlet’s mind by observing his behavior and listening to his speech? Can we know whether our actions will have the consequences we want them to have? Can we know anything about the afterlife? Many people have seen Hamlet as a play about indecisiveness, and thus about Hamlet’s failure to act appropriately. It might be more interesting to consider that the play shows us how many uncertainties our lives are built upon, how many unknown quantities are taken for granted when people act or when they evaluate one another’s actions. The Complexity of Action Directly related to the theme of certainty is the theme of action. How is it possible to take reasonable, effective, purposeful action? In Hamlet, the question of how to act is affected not only by rational considerations, such as the need for certainty, but also by emotional, ethical, and psychological factors. Hamlet himself appears to distrust the idea that it’s even possible to act in a controlled, purposeful way. When he does act, he prefers to do it blindly, recklessly, and violently. The other characters obviously think much less about “action” in the abstract than Hamlet does, and are therefore less troubled about the possibility of acting effectively. They simply act as they feel is appropriate. But in some sense they prove that Hamlet is right, because all of their actions miscarry. Claudius possesses himself of queen and crown through bold action, but his conscience torments him, and he is beset by threats to his authority (and, of course, he dies). Laertes resolves that nothing will distract him from acting out his revenge, but he is easily influenced and manipulated into serving Claudius’s ends, and his poisoned rapier is turned back upon himself. 15 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide The Mystery of Death In the aftermath of his father’s murder, Hamlet is obsessed with the idea of death, and over the course of the play he considers death from a great many perspectives. He ponders both the spiritual aftermath of death, embodied in the ghost, and the physical remainders of the dead, such as by Yorick’s skull and the decaying corpses in the cemetery. Throughout, the idea of death is closely tied to the themes of spirituality, truth, and uncertainty in that death may bring the answers to Hamlet’s deepest questions, ending once and for all the problem of trying to determine truth in an ambiguous world. And, since death is both the cause and the consequence of revenge, it is intimately tied to the theme of revenge and justice—Claudius’s murder of King Hamlet initiates Hamlet’s quest for revenge, and Claudius’s death is the end of that quest. The question of his own death plagues Hamlet as well, as he repeatedly contemplates whether or not suicide is a morally legitimate action in an unbearably painful world. Hamlet’s grief and misery is such that he frequently longs for death to end his suffering, but he fears that if he commits suicide, he will be consigned to eternal suffering in hell because of the Christian religion’s prohibition of suicide. In his famous “To be or not to be” soliloquy (III.i), Hamlet philosophically concludes that no one would choose to endure the pain of life if he or she were not afraid of what will come after death, and that it is this fear which causes complex moral considerations to interfere with the capacity for action. The Nation as a Diseased Body Everything is connected in Hamlet, including the welfare of the royal family and the health of the state as a whole. The play’s early scenes explore the sense of anxiety and dread that surrounds the transfer of power from one ruler to the next. Throughout the play, characters draw explicit connections between the moral legitimacy of a ruler and the health of the nation. Denmark is frequently described as a physical body made ill by the moral corruption of Claudius and Gertrude, and many observers interpret the presence of the ghost as a supernatural omen indicating that “[s]omething is rotten in the state of Denmark” (I.iv.67). The dead King Hamlet is portrayed as a strong, forthright ruler under whose guard the state was in good health, while Claudius, a wicked politician, has corrupted and compromised Denmark to satisfy his own appetites. At the end of the play, the rise to power of the upright Fortinbras suggests that Denmark will be strengthened once again. Motifs Motifs are recurring structures, contrasts, and literary devices that can help to develop and inform the text’s major themes. Incest and Incestuous Desire The motif of incest runs throughout the play and is frequently alluded to by Hamlet and the ghost, most obviously in conversations about Gertrude and Claudius, the former brother-in-law and sister-in-law who are now married. A subtle motif of incestuous desire can be found in the relationship of Laertes and Ophelia, as Laertes sometimes speaks to his sister in suggestively 16 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide sexual terms and, at her funeral, leaps into her grave to hold her in his arms. However, the strongest overtones of incestuous desire arise in the relationship of Hamlet and Gertrude, in Hamlet’s fixation on Gertrude’s sex life with Claudius and his preoccupation with her in general. Misogyny Shattered by his mother’s decision to marry Claudius so soon after her husband’s death, Hamlet becomes cynical about women in general, showing a particular obsession with what he perceives to be a connection between female sexuality and moral corruption. This motif of misogyny, or hatred of women, occurs sporadically throughout the play, but it is an important inhibiting factor in Hamlet’s relationships with Ophelia and Gertrude. He urges Ophelia to go to a nunnery rather than experience the corruptions of sexuality and exclaims of Gertrude, “Frailty, thy name is woman” (I.ii.146). Ears and Hearing One facet of Hamlet’s exploration of the difficulty of attaining true knowledge is slipperiness of language. Words are used to communicate ideas, but they can also be used to distort the truth, manipulate other people, and serve as tools in corrupt quests for power. Claudius, the shrewd politician, is the most obvious example of a man who manipulates words to enhance his own power. The sinister uses of words are represented by images of ears and hearing, from Claudius’s murder of the king by pouring poison into his ear to Hamlet’s claim to Horatio that “I have words to speak in thine ear will make thee dumb” (IV.vi.21). The poison poured in the king’s ear by Claudius is used by the ghost to symbolize the corrosive effect of Claudius’s dishonesty on the health of Denmark. Declaring that the story that he was killed by a snake is a lie, he says that “the whole ear of Denmark” is “Rankly abused. . . .” (I.v.36–38). Symbols Symbols are objects, characters, figures, and colors used to represent abstract ideas or concepts. Yorick’s Skull In Hamlet, physical objects are rarely used to represent thematic ideas. One important exception is Yorick’s skull, which Hamlet discovers in the graveyard in the first scene of Act V. As Hamlet speaks to the skull and about the skull of the king’s former jester, he fixates on death’s inevitability and the disintegration of the body. He urges the skull to “get you to my lady’s chamber, and tell her, let her paint an inch thick, to this favor she must come”—no one can avoid death (V.i.178–179). He traces the skull’s mouth and says, “Here hung those lips that I have kissed I know not how oft,” indicating his fascination with the physical consequences of death (V.i.174–175). This latter idea is an important motif throughout the play, as Hamlet frequently makes comments referring to every human body’s eventual decay, noting that Polonius will be eaten by worms, that even kings are eaten by worms, and that dust from the decayed body of Alexander the Great might be used to stop a hole in a beer barrel. 17 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Pre-Show Discussion Questions 6th – 8th grade 1. Have you ever seen a Shakespeare play before? Where? What was it, and what did you think of it? 2. What are some of the challenges of watching a Shakespeare play? 3. How do you think actors and directors can meet those challenges and help an audience out? 4. Given what you’ve heard about the story and the characters so far, what would you say were some of the challenges that the characters in the story face? 5. Before you see the play acted out, why do you think it’s so hard for Hamlet to obey the command of his father’s ghost? 6. Why do you think Laertes and Polonius didn’t want Ophelia spending time with Hamlet? 7. What do you think about Ophelia obeying her father and her brother when they tell her to stay away from Hamlet? 8. What do you think drove Ophelia mad? 9. What do you think of Polonius as a father? 10.What do you think of Gertrude as a mother? Do you think it was right for her to marry her husband’s brother almost immediately following old Hamlet’s death? Can you understand why Hamlet is upset about it? 9th – 12th grade (although they might have fun with the questions above, as well) (Based on the National Players As You Like It Study Guide from the Olney Theatre Center in Olney, MD) 1. Discuss your previous experiences with Shakespeare and his plays. Did you find them difficult to understand, or tedious to read? Could you understand what the actors were saying? 2. Do you find the language in Shakespeare beautiful and poetic, or does the archaic language just frustrate you and hinder understanding? 3. Have you seen any of the recent modern versions of Shakespeare plays? Did updating them make them feel more relevant to your own life? Why or why not? 4. Having read the synopsis of Hamlet, what scene and/or relationship are you most excited to watch? 5. If you were in Hamlet’s situation, would you trust the Ghost? Why or why not? 18 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Hamlet Trivia—Just for Fun Famous Quotes You may find yourself recognizing lines from Hamlet, having heard them before without ever realizing where they came from. Take a look at the lines below, and then see if you can catch them as they are spoken in our production: A little more than kin and less than kind! Hamlet; I.1 O that this too, too solid flesh would melt... Hamlet, I.2 Frailty, thy name is woman! Hamlet, I.2 This above all else: to thine own self be true. Polonius, I.3 Something is rotten in the state of Denmark. Marcellus, I.4 The time is out of joint. O cursed spite/That ever I was born to set it right! Hamlet, I.5 … brevity is the soul of wit. Polonius, II.2 Though this be madness, yet there is method in’t. Polonius, II.2 ...there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so. Hamlet, II.2 What a piece of work is a man! Hamlet, II.2 O, what a rogue and peasant slave am I! Hamlet, II.2 The play’s the thing/Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the King. Hamlet, II.2 To be or not to be, that is the question. Hamlet, III.1 Speak the speech, I pray you... Hamlet, III.2 O, my offense is rank, it smells to heaven... Claudius, III.3 The lady doth protest too much methinks. Gertrude, III.2 How all occasions do inform against me/And spur my dull revenge! Hamlet, IV.4 There’s such divinity doth hedge a king... Claudius, IV.5 Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio. Hamlet, V.1 There’s a divinity that shapes our ends/Rough-hew them how we will. Hamlet, V.2 Now cracks a noble heart. Horatio, V.2 Compiled by Deborah James for the National Arts Centre English Theatre, Dec. 2003 19 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Elsinore Castle, Denmark What Was a Castle? From the Cummings Study Guides, www.shakespearestudyguide.com/Macbeth.html#Macbeth .......Many of the scenes in Hamlet are set in a castle. A castle was a walled fortress of a king or lord. The word castle is derived from the Latin castellum, meaning a fortified place. Generally, a castle was situated on an eminence (a piece of high ground) that had formed naturally or was constructed by laborers. High ground constructed by laborers was called a motte (French for mound); the motte may have been 100 to 200 feet wide and 40 to 80 feet high. The area inside the castle wall was called the bailey. .......Some castles had several walls, with smaller circles within a larger circle or smaller squares within a larger square. The outer wall of a castle was usually topped with a battlement, a protective barrier with spaced openings through which defenders could shoot arrows at attackers. This wall sometimes was surrounded by a water-filled ditch called a moat, a defensive barrier to prevent the advance of soldiers, horses and war machines. At the main entrance was a drawbridge, which could be raised to prevent entry. Behind the drawbridge was a portcullis [port KUL is], or iron gate, which could be lowered to further secure the castle. Within the castle was a tower, or keep, to which castle residents could withdraw if an enemy breached the portcullis and other defenses. Over the entrance of many castles was a projecting gallery with machicolations [muh CHIK uh LAY shuns], openings in the floor through which defenders could drop hot liquids or stones on attackers. In the living quarters of a castle, the king and his 20 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide family dined in a great hall on an elevated platform called a dais [DAY is], and they slept ichamber called a solar. The age of castles ended after the development of gunpowder and artillery fire enabled armies to breach thick castle walls instead of climbing over them. Elsinore Castle, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons 21 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Famous Hamlets Over the Years With 1,438 lines, or approximately 36% of the lines in the play, the role of Hamlet is the longest role in Shakespeare’s Canon (collected works). It was originally written for Richard Burbage, the leading player in Shakespeare’s company, and a long-standing favorite of the playwright. Legend has it that when Burbage first read the play, he worried that he was a little old to play the young student prince. He was dismayed at the number of lines, and the physical endurance the role would demand. He is reported to have insisted that Shakespeare take Hamlet offstage during Act IV, so that Burbage could put his feet up in the dressing room and have a bit of a rest before the big Act V swordfight finish. Shakespeare is said to have asked sarcastically just what he was supposed to have happen onstage while Burbage refreshed himself. “Oh,” the actor is said to have replied, “Why not give the little girl a mad scene?” And so Ophelia’s famous mad scene was born. Burbage had great success in the role, and ever since, playing Hamlet is considered the apex of an actor’s career. Some of the most famous, celebrated actors in the world have attempted it over the years, with varying degrees of success. The famous 19th century French actress, Sarah Bernhardt (The Divine Sarah!) took on the role, and is said to have been quite good. She even continued reciting exerpts after her leg was amputated, and she toured with the Barnum & Bailey Circus. 22 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Sir Lawrence Olivier stands among the most famous Hamlets of the 20th Century, playing the role onstage as well as producing and directing a film of the play, in which he starred. Olivier’s colleague on the English stage, John Gielgud also played a well-received Hamlet, albeit a very different interpretation from Olivier’s. 23 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Gielgud directed a famous Broadway production of HAMLET starring the popular Welsh actor, Richard Burton. This production was famous for daring to strip all set design and costuming down to bare essentials, presenting in a modern style that eliminated all the “fuss” that Gielgud claimed distracted actors from the valid work that goes into rehearsals. He believed that having to adjust to new costumes, sets, props just before opening interfered with actors’ ability to focus on the essence of language and truthful performance. This production came at the height of the controversial debate over which was the more valid style of acting: Technical (British school) or Method (American school). American actor Edwin Booth was said to have been a very good Hamlet, circa the 1870’s. 24 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide If Hamlet is played unedited, it can last up to five hours. In 1996, British actor Kenneth Branaugh directed an uncut film version of Hamlet. He kept every single word, himself playing the title role. The cast was studded with stars—Kate Winslet as Ophelia, Derek Jacoby as Claudius, Julie Christie as Gertrude, Judi Dench as Hecuba, John Gielgud as Priam, and famous stand-up comedian Robin Williams in the tiny role of the Elizabethan fop, Osric. Top French film star Gerard Depardieu appeared in the tiny cameo role of Reynaldo, Jack Lemmon played the guard, Marcellus. Other heavy-hitters in the company included Charlton Heston as the Player King and Billy Crystal as the first Gravedigger. 25 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Some Context for the Plays Shakespeare’s Audience It is very helpful to have an idea about who Shakespeare was writing for, back in the 16th century. His audience was very different from theatre goers today. In the first place, it was a much more articulate age. People were in love with language, and took great pride in finding exactly the right words or phrases to describe how they felt or thought. Today, if someone asks “How are you feeling?” we tend to reply simply “fine” or “junk,” or some other monosyllabic answer, depending on the kind of day we’re having. This tendency toward verbal shorthand is encouraged by the use of texting, tweeting, Facebook messaging, etc., all of which demand the briefest of short-speak. In Shakespeare’s day, however, people could go on at great lengths to answer a simple question, to describe something they’d seen, or to philosophize about life in general. Consider this: in ActII.ii., when Hamlet asks Rosenkrantz and Guidenstern whether or not they have come to Elsinore of their own free will or have been sent for, they hesitate to answer. Hamlet then describes in exquisite detail what has been happening to him. I have of late, but wherefore I know not, lost all my mirth, forgone all custom of exercise; and indeed it goes so heavily with my disposition that this goodly frame the earth seems to me a sterile promontory, this most excellent canopy the air, look you, this brave o’erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire, why, it appeareth nothing to me byt a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours. Shakespeare himself had a vocabulary of over 30,000 words (today, an average person’s vocabulary is between 8,000 – 10,000 words), and if he couldn’t find exactly the word or phrase he wanted, he’d make something up! His articulate audiences loved this about his writing, and went to hear his plays more than to see them. Shakespeare created characters that take delight finding the perfect words to express an emotion, or describe a scene. Actors who are able to discover and convey this delight with the language are by far the most exciting to watch as well as listen to. They are also the easiest to understand. As you watch our Hamlet, see who you think is really getting the most out of the words. 26 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre courtesy of www.videojug.com FUN FACT: In Elizabethan times many of Shakespeare’s plays were performed at The Globe Theatre in London. To get in, you put one penny in a box by the door. Then you could stand on the ground in front of the stage. To sit on the first balcony, you put another penny in the box held by a man in front of the stairs. To sit on the second balcony, you put another penny in the box held by the man by the second flight of stairs. Then when the show started, the men went and put the boxes in a room backstage—hence the “box office.” --BBC http://www.bbc.co.uk/coventry/features/shakespeare/ shakespeare-fun-facts.shtml 27 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide How to Listen to Shakespeare (From the on the National Players As You Like It Study Guide from the Olney Theatre Center in Olney, MD) When watching a Shakespearean play, there are many things to keep in mind. Sometimes the language in which Shakespeare writes can be difficult to understand, but once you do, it's really great fun. First and foremost, you don’t have to understand every word that’s being said in order to understand the play. Don’t get too hung up on deciphering each word; instead, just try to grasp the gist of what each character is saying. After a while, you won’t even have to think about it—it will seem as if you’ve been listening to Shakespeare all your life! Watch body language, gestures, and facial expressions. Good Shakespearean actors communicate what they are saying through their body. In theory, you should be able to understand much of the play without hearing a word. There is a rhythm to each line, almost like a piece of music. Shakespeare wrote in a form called iambic pentameter. Each line is made up of five feet (each foot is two syllables) with the emphasis on the second syllable. You can hear the pattern of unstressed/stressed syllables in the line, What PA / ssion HANGS/ these WEIGHTS / up ON/ my TONGUE? Listen for this pattern in the play as it adds a lyrical quality to the words. Read a synopsis or play summary ahead of time. Shakespeare’s plays involve many characters in complex, intertwining plots. It always helps to have a basic idea of what’s going on beforehand so you can enjoy the play without trying to figure out every relationship and plot twist. 28 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Playing Shakespeare: Grappling with the Language as an Actor Rule #1 in performing Shakespeare: KNOW WHAT YOU ARE SAYING! Bit of trivia: when William Shakespeare was writing plays, the English language was growing by leaps and bounds, and the playwrights of the day were adding to it with every play they wrote. Playwrights back then were very much like rap and hip-hop artists today, stretching and playing with language; in fact, if Shakespeare were alive today, he’d most likely be a slam poet! FUN FACT from the BBC: Shakespeare invented words and phrases that we use all the time without even knowing where they come from. Shakespeare was the first to use words like critic, majestic, hurry, lonely, reliance, and exposure. He also created hundreds of common phrases like break the ice, hotblooded, elbow room, love letters, puppy dog, and wild goose chase. BBC http://www.bbc.co.uk/coventry/features/shakespeare/shakespeare-fun-facts,shtml Another bit of trivia: Pay attention to Shakespeare’s “O’s!” An “O” at the start of a line was Shakespeare’s gift to his favorite actors. That open and most versatile vowel gives an actor the chance to vocalize the pure emotion underneath his line, even before he starts to say the words. Listen for the “O’s” in Hamlet. Tools for the Text 1: Paraphrase Reading a Shakespeare play can be a daunting task. Whether it is a class requirement, or a personal project, Shakespeare’s language can make it difficult to lose yourself within its pages. However, there are a few tools you can use to help break down the text into something both understandable and enjoyable. The first tool is called Paraphrasing. This is when you take the text and put it into your own words. This is not only a useful tool for reading the language, but it is the primary method of deconstructing the text used by actors rehearsing for Shakespeare’s plays. Although the words used 400 years ago are similar, their meaning was quite different, in some cases. Examine the following lines from a well-known passage in Hamlet: 29 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide This speech of Ophelia’s takes place immediately after Hamlet has exploded at her, attacking her verbally (in some productions, physically, too), telling her to “get thee to a nunnery!” She is crushed, believing his fit to be evidence of his descent into madness—something she is afraid she has caused by obeying her father and staying away from Hamlet, who had sworn his love for her before. As soon as Hamlet has stormed off, Ophelia collapses to the ground and laments: O, what a noble mind is here o’erthrown! The courtier’s, soldier’s, scholar’s, eye, tongue, sword, Th’expectancy and rose of the fair state, The glass of fashion and the mould of form, Th’observed of all observers, quite, quite down! And I, of ladies most deject and wretched, That sucked the honey of his music vows, Now see that noble and most sovereign reason Like sweet bells jangled out of tune and harsh, That unmatched form and feature of blown youth Blasted with ecstasy. O woe is me T’have seen what I have seen, see what I see. Now here’s the paraphrasing that the good people at SIMPLY SHAKESPEARE suggest: Oh, what a noble mind is lost here! His looks, speech, and skill of a courtier, soldier, and scholar; the hope and ornament of the kingdom he made lovely; the mirror of noble attention— completely, completely destroyed! And I—the most miserable and sorrowing of women, who feasted on the honey of his sweetly spoken vows—I now see his noble and surpassingly powerful mind all jangled like sweet bells ringing harshly out of tune. That unmatched example of blooming youth is blighted with madness. Oh, such woe has befallen me—that I have seen what I have seen, that I see what I see now! It may be clear, but it certainly sounds flat when compared with the original! 30 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Tools for the Text 2: Imagery Another great tool to further and deepen your understanding of Shakespeare is imagery. These are the pictures that Shakespeare paints with specific words. Just as pictures go through your mind when you read a book, Shakespeare used even more profound words to create very powerful images. Read the original text of Ophelia’s monologue above again, then take a look at the words and phrases below. Step one is to write down the first few images that come into your mind: Noble mind:_______________________________________________________________ O’erthrown:_______________________________________________________________ Rose of the fair state:________________________________________________________ Glass of fashion:___________________________________________________________ Mould of form:____________________________________________________________ Observed of all observers:_____________________________________________________ Deject and wretched:__________________________________________________________________ Honey of his music vows:______________________________________________________________________ Sweet bells jangled:___________________________________________________________ Blown youth:________________________________________________________________ Blasted with ecstasy:__________________________________________________________ Now ask yourself what those images mean to you. How do they make you feel? What kind of actions do they make you want to do? What words affect you most? Once you’ve found some personal connection to these words, say the monologue out loud and allow those images to fill your mind. Allow them to affect you and your audience as you speak. 31 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Tools for the Text 3: Working With Iambic Pentameter Take a look at the monologue in the previous two examples. Do you notice a rhythm to the lines when you say them? This is because Shakespeare chose to write much of his text in Iambic Pentameter. You’ll find many explanations for what this means, but one simple way is to say that each line has 10 syllables – 5 stressed and 5 unstressed. Here is an example from Hamlet, the opening lines of the famous “Hecuba” speech after the Players have come to Elsinore Castle, and one of the players, while reciting a powerful speech, has been carried away by the emotion of the fictional character he enacts. Hamlet is angry with himself, because with all of the very real reasons he has to be overcome with emotion, he is incapable of expressing his passion as the actor has done while simply pretending. O, what a rogue and peasant slave am I! Is it not monstrous that this player here, But in a fiction, in a dream of passion, Could force his soul so to his own conceit That from her working all his visage waned, Tears in his eyes, distraction in his aspect, A broken voice, and his whole function suiting With forms to his conceit? And all for nothing! Count the syllables. You can see that each line has 10 syllables. Now we will break the line up into smaller sections that have two syllables. These sections are called feet. O, what a rogue and peas ant slave am I! Watch out when breaking a line into feet. You’ll notice that sometimes a word can be broken up (like peas-ant). Now, within each foot there is usually one stressed and one unstressed syllable. In Iambic Pentameter, the second syllable in a foot usually gets the strong stress. You’ll notice, though, that at the end of the third line of the speech, there’s an extra, unstressed beat in the final foot (pas sion), this is known as a feminine ending to the line. One easy way to remember how the stresses work in Iambic Pentameter is that it sounds like you were to say “eye-am” five times with the heavier beat on the second half of the foot. Try it: I am I am I am I am I am 32 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide There are several reasons why Shakespeare used this form for his writing. One was because of its beautiful sound and the strong rhythm which is similar to the beating of the human heart. Another was that Iambic Pentameter is very close to the normal rhythm of every day conversation in the English language. This helped the actors memorize their lines since, 400 years ago, they only had a few days of rehearsal before performing a play. Another was that it gives the actor the choice as to which words are more important. When an actor goes through his/her script to mark the feet and decide what syllables get the stresses it is called scanning the script. Try it: 1. O, what 2. Is it 3. But in a rogue and peas ant slave am I! not mon strous that this play er here, a fict 4. Could force 5. That from ion, in a dream his soul so to her work ing all of pass ion, his own his vis 6. Tears in his eyes, distract ion in 7. A bro ken voice, and his 8. With forms to his conceit age wanned, his as pect, whole func tion suiting conceit? And all for no thing! (Note that lines 3, 6, 7 and 8 all have feminine endings.) Did you make every other syllable strong? Or did you decide that some syllables were more important than others whether or not the iambic pentameter stressed them? This is one thing that makes acting Shakespeare so much fun! Actors get to choose what words and phrases they feel are important, given their interpretation of the character. The thing that makes iambic pentamenter so helpful is that if there is a question about which word(s) Shakespeare considered important, you can be sure that they will always be the ones in the stressed portion of a foot, when working with the standard iambic pentameter stress pattern. Tools of the Text 1, 2, and 3 are based on the Orlando – UCF Shakespeare Festival Twelfth Night Study Guide, adapted to suit Hamlet 33 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Just for Fun: Shakespearean Insults You’ve read how “serious” actors approach playing Shakespeare, now let’s have some fun. Shakespeare gives his characters terrific verbal fodder for some of the most creative insults ever slung. What does Hamlet say when he discovers he’s killed Polonius, eavesdropping behind the arras? He lets fly a series of colorful adjectives that let his audience know exactly how he feels about Polonius. Thou wretched, rash, intruding fool, farewell/I took thee for thy better… Below are three lists of words. Columns 1 and 2 are highly descriptive adjectives from Elizabethan English (a number of them, no doubt, made up by Shakespeare himself). Column 3 consists of equally colorful nouns. Start with the word “thou” (a very familiar way to address someone—a term of endearment if used with a loved one, an insult if used to address either a stranger or an adversary). Then pick one word from each column, creating your very own customized insult. It’s lots of fun for students to stand on opposite sides of a room and hurl their insults across the room at each other. Be sure to savor the taste and feel of the words in your mouth, and get as much value out of the vowels and consonants as possible! Example: Thou reeky, rump-fed pumpion! Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 Artless Bawdy Beslubbering Bootless Churlish Cockered Clouted Craven Currish Dankish Dissembling Droning Errant Fawning Fobbing Forward Frothy Gleeking Goatish base-court bat-fowling beef-witted beetle-headed boil-brained clapper-clawed clay-brained common-kissing crook-pated dismal-dreaming dizzy-eyed doghearted dread-bolted earth-vexing elf-skinned fat-kidneyed fen-sucked flap-mouthed fly-bitten apple-john baggage barnacle bladder boar-pig bugbear bum-bailey canker-blossom clack-dish clotpole coxcomb codpiece death-token dewberry flap-dragon flax-wench flirt-gill foot-licker fustilarian 34 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide (Shakespearean Insults, cont.) Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 Gorbellied Impertinent Infectious Jarring Loggerheaded Lumpish Mammering Mangled Mewling Paunchy Pribbling Puking Puny Qualling Rank Reeky Roguish Ruttish Saucy Spleeny Spongy Surly Tottering Unmuzzled Vain Venomed Villainous Wayward Yeasty folly-fallen fool-born full-gorged guts-griping half-faced hasty-witted hedge-born hell-hated idle-headed ill-breeding ill-nurtured knotty-pated milk-livered motley-minded onion-eyed plume-plucked pottle-deep pox-marked reeling ripe rough-hewn rude-growing rump-fed shard-borne sheep-biting spur-galled swag-bellied tardy-gaited toad-spotted weather-bitten giglet gudgeon haggard harpy hedge-pig horn-beast hugger-mugger joithead lewdster lout maggot-pie malt-worm mammet measle minnow miscreant moldwarp mumble-news nut-hook pigeon-egg pignut puttock pumpion ratsbane scut skainsmate strumpet vassal wagtail Shakespearean insult image courtesy of www.michaelcoady.com 35 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide About William Shakespeare (This history is largely from The English Theatre Frankfurt) Fast Facts Born: Education: Marriage: Children: 1564, Stratford-upon-Avon, England Left school at 14 because of his family’s financial problems Wed Anne Hathaway when he was 18 (shotgun wedding!) Three: one daughter, Susanna, and a sickly set of twins. Hamnet and Judith First job: Actor Mystery: Disappeared between 1585-1592, no record of his whereabouts Theatre co: The King’s Men Most famous play: Romeo & Juliet A Very Bad Beginning: William Shakespeare was born in 1564 in a half-timbered house in Henley Street, Stratfordupon-Avon. His father was John Shakespeare, a glove maker and wool-dealer. His mother was Mary Arden, daughter of a farmer from Wilmcote. Young William attended the Stratford Grammar School form the age of 7 until he was 14. The grammar school was held on the upper 36 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide floor of the old Guildhall, and here the classes were held in Latin, concentrating on Grammar and the ancient classics of Greece and Rome. Shakespeare was withdrawn from school due to his family’s financial difficulties, and never completed his education, which makes his subsequent accomplishments all the more remarkable. True love? At the age of 18, Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway, daughter of a yeoman farmer from Shottery, close to Stratford. The marriage may have been forced, as Anne was already 3 months pregnant with a daughter, Susanna. This first child was followed by sickly twins – Hamnet and Judith – in 1585. Disappearance! The next 7 years of Shakespeare’s life are a mystery, though he is rumored to have worked as a schoolteacher. Sometime before 1592 Shakespeare fled his home and family to follow the life of an actor in London. The Black Plague hits England London’s theatres were closed in January 1593 due to an outbreak of the plague, and many players left the capital to tour the provinces. Shakespeare preferred to stay in London, and it was during this time of plague that he began to gain recognition as a writer, notably of long poems, such as Venus and Adonis, and Rape of Lucrece. The Tide Turns Shakespeare was fortunate to find a patron, Henry Wriothsley, Earl of Southampton, to support him in his writing. Venus and Adonis was wildly successful, and it was this work that first brought the young writer widespread recognition. Apart from his longer poetry, Shakespeare also began writing his sonnets during this period, perhaps at the behest of Southampton’s mother, who hoped to induce her son to marry. All the King’s Men When the theatres reopened in late 1594, Shakespeare was no longer a simple actor, but a playwright as well, writing and performing for the theatre company called “Lord Chamberlain’s Men,” which later became “The King’s Men.” Shakespeare Gets Rich Shakespeare became an investor in the company, perhaps with money granted him by his patron, Southampton. It was this financial stake in his theatre company that made Shakespeare’s fortune. For the next 17 years he produced an average of 2 plays a year for The King’s Men. But It’s Never Easy in the Arts! The early plays were held at The Theatre, to the north of the city. In 1597 the company’s lease on The Theatre expired, and negotiations with the landlord proved fruitless. Taking advantage of a clause in the lease that allowed them to dismantle the building, the company took apart the place board by board and transported the material across the Thames River to Bankside. 37 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide The Globe Is Built There they constructed a new circular theatre, the grandest yet seen, called The Globe. The Globe remained London’s premier theatre until it burned down in 1613 during a performance of Shakespeare’s Henry VIII. Shakespeare Goes Home Shakespeare held a share in the profits from The Globe, which netted him a princely annual income of £200-£250. His financial success enabled Shakespeare to purchase New Place, the second largest house in Stratford. It was here that he retired around 1611. Sorry, Anne When he died 1616, William Shakespeare divided up his considerable property amongst his daughters (his son, Hamnet had died in childhood), but left only his second best bed to his wife. Anne. Shakespeare was buried in the chancel of Holy Trinity Church in Stratford. FUN FACT: No one really knows when Shakespeare was born. Tradition holds that his birthday is April 23, 1564. However, all we know for sure is that he was baptized three days later at Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon. April 23 became popularly established as his birthday after he died on the same day in 1616. (From the on the National Players As You Like It Study Guide from the Olney Theatre Center in Olney, MD) 38 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Shakespeare’s Theatre (From the on the National Players As You Like It Study Guide from the Olney Theatre Center in Olney, MD) The theatre scene that Shakespeare found in London in the late 1580s was very different from anything existing today. Because he was directly affected by and wrote specifically for this world, it is very important to understand how it worked. The Performance Space The Globe Theatre was a circular wooden structure constructed of three stories of galleries (seats) surrounding an open courtyard. It was an open-air building (no roof), and a rectangular platform projected into the middle of the courtyard to serve as a stage. The performance space had no front curtain, but was backed by a large wall with three doors out of which actors entered and exited. In front of the wall stood a roofed house-like structure supported by two large pillars, designed to provide a place for actors to “hide” when not in a scene. The roof of this structure 39 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide was referred to as the “Heavens.” The theatre itself housed up to 3,000 spectators, mainly because not all were seated. The seats in the galleries were reserved for people from the upper classes who came to the theatre primarily to “be seen.” These wealthy patrons were also sometimes allowed to sit on or above the stage itself as a sign of their prominence. These seats, known as the “Lord’s Rooms,” were considered the best in the house despite the poor view of the back of the actors. The lower-class spectators, however, stood in the open courtyard and watched the play on their feet. These audience members became known as “groundlings” and gained admission to the playhouse for as low as one penny. The groundlings were often very loud and rambunctious during the performances and would eat (usually hazelnuts), drink, socialize as the play was going on, and shout directly to the actors on stage. Playwrights at this time were therefore forced to incorporate lots of action and bawdy humor in their plays in order to keep the attention of their audience. The Performance During Shakespeare’s day, new plays were being written and performed continuously. A company of actors might receive a new play, prepare it, and perform it every week. Because of this, each actor in the company had a specific type of role that he normally played and could perform with little rehearsal. One possible role for a male company member, for example, would be the female ingénue. Because women were not allowed to perform on the stage at the time, young boys whose voices had yet to change generally played the female characters in the shows. Each company (composed of 10 – 20 members) would have one or two young men to play the female roles, one man who specialized in playing a fool or clown, one or two men who played the romantic male characters, and one or two who played the mature, tragic characters. Along with the “stock” characters of an acting company, there was also a set of stock scenery. Specific backdrops, such as forest scenes or palace scenes, were re-used in every play. Other than that, however, very minimal set pieces were present on the stage. There was no artificial lighting to convey time and place, so it was very much up to audience to imagine what the full scene would look like. Because of this, the playwright was forced to 40 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide describe the setting in greater detail than would normally be heard today. For example, in order to let an audience know that the sun is coming up in Act I.i, just after the Ghost of Hamlet’s father has retreated, Shakespeare gives Horatio the following line: But look, the morn, in russet mantle clad, Walks o’er the dew of yon high eastward hill... What a beautiful way to describe the dawn! Listen for this line in Act I. Unlike the natural lighting, the costumes of this period were far from minimalist. These were generally rich and luxurious, as they were a source of great pride for the performers who personally provided them. However, these were rarely historically accurate and again forced the audience to use their imaginations to envision the play’s time and place. In our production, because we are telling the story using the conceit of our vagabond troupe of Elizabethan players, (a company that is not all that affluent), we have imagined that each of the actors has spent most of his salary on the one costume element that will most clearly define his role. Cutaway drawing of The Globe Theatre 41 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Meet Our Players Here are the talented and hard-working members of this year’s Hawaii Young Actors Ensemble. For this production, each has created his/her male Elizabethan Player. The Cast Actor Elizabethan Player Role(s) in Hamlet Taylor Aitaro Mr. Kain, Company Mgr. Player King Frank Coffee Draco Rosenkrantz *Madison Darcey Boyo Bernardo, 2nd Gravedigger, Officer Emma Eckfeldt Arthur Francisco, Sailor, Officer Erin Elise Gillum Grayson Fortinbras *Mickey Graue Marcus Laertes Brianna Hayes Valentine Ophelia Kelley Heyer Henry Claudius #Crystal Hughes Nigel Horatio Maya Jennings Gregory Gertrude #Brianne Johnson Geoffrey Player Queen **Michael Main Richard Hamlet *Kaley Mayo Leonardo Priest #Ashley McHenry Elijah Marcellus Gabriella Munoz Nicholas Lucianus Wesley Phelps Mr. Gibby (company dwarf) Court Jester, 1st Gravedigger #Danielle Schum Mark (company costumer) Reynaldo William Thai Gregory Guildenstern Benen Weir Valentine Osric ***Malia Wessel Gavin Cameron Webb Polonius Ghost Puppet Operators: Gabrielle Munoz, Danielle Schum, Erin Elise Gillum, Kaley Mayo, Madison Darcey, Ashley McHenry. ________________________________________________________________________________ # former Hawaii Theatre Junior Ensemble Member * Second year HTYAE member ** Third year HTYAE member ***Fourth year HTYAE member 42 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Our Production Team Director/Producer…………….Eden-Lee Murray Production Stage Manager……Nilva Panimdim Set Designer…………………..Bart McGeehon Lighting Designer……………..Janine Myers Light Board Operator………….Hope Laidlaw* Costume Designer……………..Peggy Krock Costume Assistant…………….Malia Wessel** Ghost Puppet Designer………...Jeff Gere Dramaturge…………………....Michael Main Fight Choreographer…………..Tony Pisculli Choreographer…………………Brianna Hayes Technical Director……………..Andrew Doan HTC Publicity……….………...Mele Pochereva Production photographer………Cheyne Gallarde, Firebird Photography Flyer/Program Designer………..Terry Nii Original Soundscape and Sound Design by Dylan Pilger _______________________________________________ *HTYAE Lighting Apprentice **HTYAE Company Member 43 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Afterglow Post-show Discussions & Activities 6th – 8th Grade Follow-up Questions: 1. What parts of the show did you like best? Why? 2. How was seeing the play different from reading it? 3. Was it easier to understand the language by watching it acted out? 4. What is the main story in HAMLET? Can you tell it in sequence? 5. The play has a number of sub-plots. Can you list them? 6. One of the important themes in the play deals acting on one’s convictions versus the inability to take action. This theme surfaces with several of the characters, not just Hamlet. Can you think of some examples? Writing Activities Expressing an Opinion: 1. Describe your favorite part of the play, and explain why you liked it. 2. Was there anything that didn’t work for you? It’s as important to understand why you don’t like something. What did you not like, and how might you have changed it? 3. In Act I. iii, Shakespeare gives Polonius a speech advising Laertes how best to live one’s life in the world. The advice concludes with: This above all: to thine own self be true, And it must follow as the night the day Thou canst not then be false to any man. And yet Polonius is a manipulative, schemer of a politician, perfectly willing to do exactly the opposite of the good counsel he gives. What do you think Shakespeare is up to here? 44 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Descriptive Writing: 1. Describe your theatre adventure: the bus ride, the Hawaii Theatre, the play. Use as many descriptive words as you can. 2. If one of our Elizabethan players visited with you before the play, describe the conversation you had—what did you learn from him? Did they help prepare you for the play? 3. Based on your experience watching the play, write a one-sentence description for each major character: Hamlet, Claudius, Gertrude, Polonius, Laertes, Ophelia, Rosenkrantz, Guildenstern. 4. A famous quote in theatre is “There are no small roles, only small actors.” The role of Osric is one of the smallest in the play, and yet our actor manages to make him memorable. How do you think he did that? 9th – 12th Grade Follow-up Questions: 1. “…there is nothing/Either good or bad but thinking makes it so.” What does this mean? How might it relate to your life? 2. “To be, or not to be, that is the question.” This is one of the most famous quotes from Shakespeare. What do you think it means? How does it apply to Hamlet’s situation? 3. “There is a special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, ‘tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come: the readiness is all.” What do you think this means, and given that Hamlet says it right before his fatal swordfight with Laertes, what do you think it means to him? 4. When Gertrude picks up the goblet to take a sip of the poisoned wine intended for Hamlet, Claudius could have stopped her, but he didn’t. Why? What do you think was going through his mind at that moment? 5. “Absent thee from felicity awhile/And in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain To tell my story.” This is what Hamlet begs of Horatio when Horatio says he wants to die along with his best friend. What is Hamlet asking Horatio to do for him, and why is it so important? 45 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Writing Activities: Personal Essay Topics 1. Why do you think Hamlet’s mother married her husband’s brother so quickly after old Hamlet’s death? 2. If you were in Hamlet’s shoes, would you have trusted the Ghost? If yes, why; and if no, why not? 3. Why do you think it was so important to Polonius that the cause of Hamlet’s madness was his love for Ophelia? 4. Why do you think Hamlet wanted to make Ophelia believe he never loved her? Was he deliberately trying to hurt her? Was he telling the truth? If you believe that he meant what he said, how can you explain his fight with Laertes in her grave, and his outpouring of grief when he learns of her death? 5. What did you think about the characters of Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern? Do you believe they might have honestly wanted to help Hamlet, or were they spying on him to curry favor with the King and Queen? Critical Analysis If you were a theatre reviewer, how would you evaluate this production? Consider first the central concept of this production—the members of the Hawaii Theatre Young Actors Ensemble assuming the roles of the band of Elizabethan players who then bring the characters in Hamlet to life—then assess the various specific elements involved: the acting, the music, the set and the costumes. 46 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Visual Arts Activity: Set Design A set designer must select elements that reflect the world(s) of the characters in the play. Play set designer: pick one of the following characters and try to design a room that might best represent them. Hamlet Claudius Gertrude Polonius Ophelia Laertes Rosenkrantz Guildenstern What do you think the Elizabethan Players’ camp might look like as they stopped along the road on their tour? Costume Design Our costume designer had to pick one costume element per character in Hamlet for each Elizabethan player to wear as he played his role within the story. If you were to costume one of the main characters in Hamlet completely, how would you want them to look? If you were to set the play in modern dress, what kind of clothing would you imagine Hamlet would wear? Ophelia? The King and Queen—how would you indicate royalty and power with a contemporary wardrobe? How would the players be dressed? 47 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide How did you like The concept of the production? The play itself? The Shakespearean language? The original music? The live soundscaping and sound f/x? The look of the show: sets/lights/costumes? The acting? Please tell us about your favorite part of the show. Is there anything you would have changed? Further comments? 48 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide Please take the time to fill out and send in this evaluation. Your comments help us improve our programming every year. Please rate GREAT GOOD FAIR POOR The quality of your students' experience. The quality of the show. Our communication with you. The Study Guide. The logistics of the show (date and time). Further comments: 49 Hawaii Theatre Student Matinee Series Hamlet Study Guide References used in compiling this Study Guide: SIMPLY SHAKESPEARE, Original Shakespearean Text With a Modern Line-for-Line Translation, edited by BARRONS SparkNotes Editors. “SparkNote on Hamlet.” SparkNotes.com. SparkNotes LLC. 2007. Web. 14 Feb. 2013. The National Players As You Like It Study Guide from the Olney Theatre Center in Olney, MD BBC http://www.bbc.co.uk/coventry/features/shakespeare/shakespeare-fun-facts,shtml 50