Complete History of ONEN - The Old North End Neighborhood

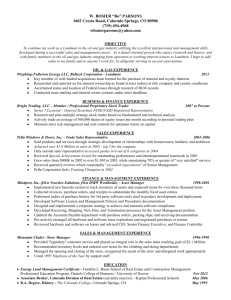

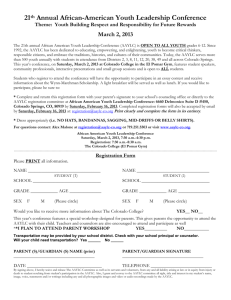

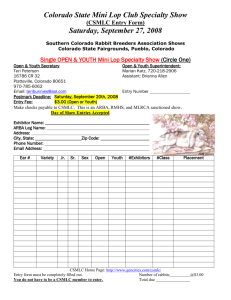

advertisement