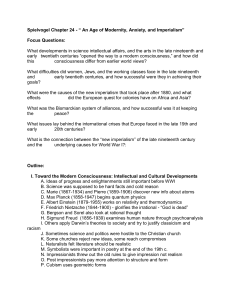

Mass Society in an “Age of Progress,” 1871–1894

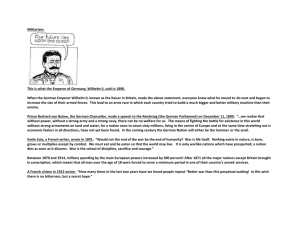

advertisement