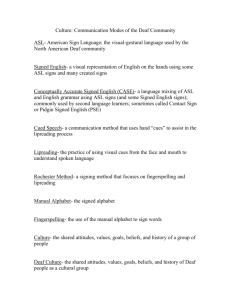

National ASL Standards - American Sign Language Teachers

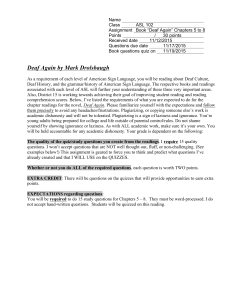

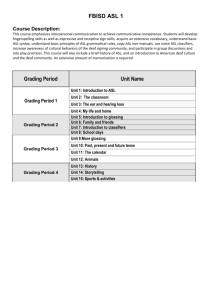

advertisement