Spring 2012 - Foundation for Landscape Studies

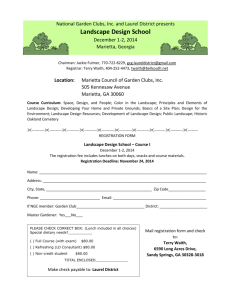

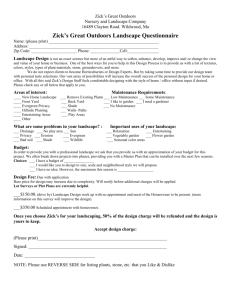

advertisement