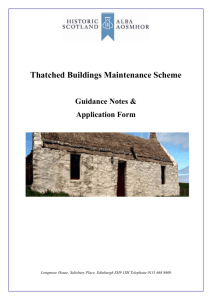

Thatch - A Guide to the Repair of Thatched Roofs (2015)

advertisement