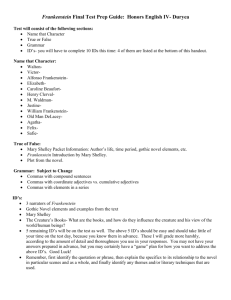

Sample Chapter - Palgrave Higher Education

advertisement