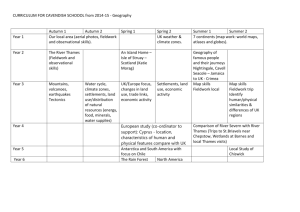

thames topics - Upper Thames River Conservation Authority

advertisement