Study Guide for - TimeLine Theatre Company

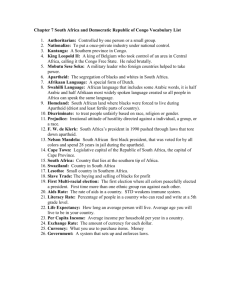

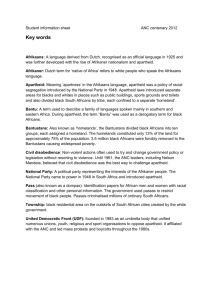

advertisement