the case of ghana - Bibliothek der Friedrich-Ebert

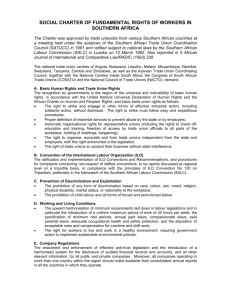

advertisement