Assignment #1 - School District of Pickens County

advertisement

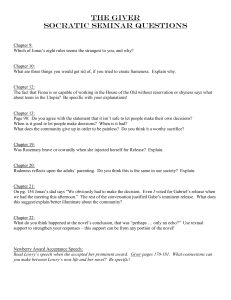

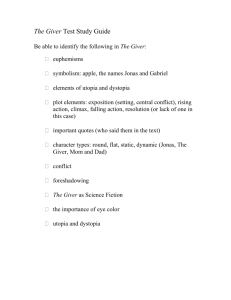

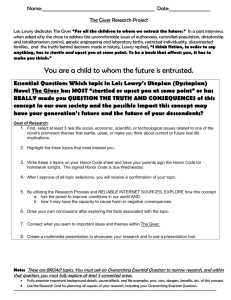

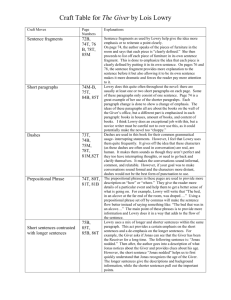

Pickens Middle School – English I Honors Required Summer Reading Assignment #1 (2015-2016) The Giver by Lois Lowry Due Date: Tuesday, August 18, 2015 Student’s Name __________________________________________ St Directions: Complete all three parts of this assignment. You must turn in this completed assignment at the beginning of class on Tuesday, August 18, 2015, the first day of school. Summer Reading assignments will be your first major grades. Please consider the presentation of your finished work; work turned in should be correct, neat, and pleasing to the eye. Your assignment must be either handwritten (in blue or black ink) or typed. You must write your answers on your own paper. Please staple your work to this hand-out, and turn in the hand-out with your work. Remember when writing about fiction, use the literary PRESENT TENSE. When describing an author’s work, however, use the PAST TENSE. You are required to read the entire novel. Your work must be your own unless you are directed to do research. You will sign a statement the first day of class saying that you read the book in its entirety and that your work is your own, original work. If you have questions, please contact Mrs. Eller (dedeeller@pickens.k12.sc.us) (tracylawson@pickens.k12.sc.us); you may also leave a message at school (864-397-4100). or Mrs. Lawson Come to class prepared for class discussion. You will take a test during the first week of class. You will be allowed to use this assignment when you take the test. Summer Reading SCORING RUBRIC Part One – Articles (4) POSSIBLE POINTS 24 points total Part Two – Characters (12) and Questions (1-16) 56 points total Part Three – Questions (17-20) 8 points total Part Three – Message from Author and Newbery Speech 12 points total TOTAL POINTS 100 points total Comments 1 EARNED POINTS Part 1 – BEFORE YOU READ . . . Directions: Read and annotate (see Hand-out #1 – “A Reader’s Guide to Annotation”) each article below (6 points each): Hand-out #2 – “Introduction to the Novel” Hand-out #3 – “The Utopian Novel” Hand-out #4 – “The Oral Tradition” Hand-out #5 – “The Hero’s Journey” Part 2 – AS YOU READ . . . Characters – Directions: As you read the novel, write a brief description (1-2 lines) of each of the characters listed below. (2 points each) The Giver – List of Characters 1. Jonas (a.k.a. the new Receiver of Memory) 2. The Giver (a.k.a. the former Receiver of Memory) 3. Asher 4. Lily 5. Mother 6. Father 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. Gabriel Fiona Committee of Elders Rosemary Caleb Katharine Chapter Questions – Directions: Answer each of the questions below using complete sentences. Use page numbers when necessary. (2 points each) Chapters 1 and 2 1. What aspects of life in Jonas’s community appeal to you? What aspects, if any, seem unappealing? 2. The novel includes many euphemisms, words that hide rather than reveal what they are describing. Usually they refer to subjects people don’t really want to talk about. Euphemisms are a way of being polite, but they can also my dangerous. As George Orwell, the author of 1984, pointed out, euphemisms can be used by governments to hide what they are really doing. In The Giver, What do you think the following euphemisms indicate? a. Assignment b. Birthmother 2 c. d. e. f. g. h. Ceremony of Loss Ceremony of Twelve Comfort Object Elders Elsewhere Newchild i. j. k. l. m. Nurturer Release Sameness Stirrings Tellings 3. Rules govern every aspect of daily life in Jonas’s community. What rules have you noticed as you read? 4. Select a short passage that you particularly like or find intriguing in Chapter 1 or Chapter 2. How and why did you choose this particular passage? Chapters 3-5 5. What point of view has Lowry chosen? What are the advantages and limitations of this point of view? 6. An allusion in literature is a reference to a famous historical, biblical, mythological, or literary person or event. Lowry has chosen to use the names Jonas, Gabriel, Asher, and Caleb. Could these names be allusions? Why might Lowry have chosen these names? Explore the meaning of these names by looking them up in an encyclopedia, book about names or on the Internet. Chapters 6-8 7. Why did the community make the distinction between “selection” for Receiver of Memory and “Assignment” for all other occupations? 8. What is the setting for The Giver? Chapters 9-11 9. What did the Giver mean when he told Jonas that honor is not the same as power? 10. Compile a list of some of the most important books that you think should be in the library of the Receiver of Memory. Include fiction, nonfiction, and reference books. Justify your selections. Chapters 12 and 13 11. Why was the Giver bitter? Chapters 14-16 12. In literature, mood is the feeling the author creates through carefully chosen words and phrases, settings, and events. What is the prevailing mood in Chapters 14 and 15? How does the mood change in Chapter 16? Why does Lowry change the mood? Is this change of mood effective? 13. Authors vary the lengths of their chapters to change rhythm and to achieve special emphasis. Reread Chapter 15. What is significant about the length of this chapter? Chapters 17-19 14. Pain, suffering, and war have been eliminated form Jonas’s world. Is this good? What does Lowry seem to think? Chapter 20 15. Every reader brings unique thoughts and experiences to a story,. Imagine that you are someone else reading this chapter. For example, you might read as a parent, a grandparent, an author, a politician, a women’s rights activist, an environmentalist, or a religious leader. Think about what that person would 3 bring to the material and how he or she might respond. What new perspective do you gain as you read? What new things do you notice about the story? What new questions and understandings do you have? Chapters 21-23 16. Why do you think the author ended the story as Jonas was still traveling toward his destination? Do you approve of the ending? Part 3 – AFTER YOU READ . . . 17. The plot of the novel builds carefully and slowly, and then gathers momentum to a stunning climax, almost like a mystery or suspense story. Lowry achieves this by carefully revealing certain details about Jonas and his world. List the major events of the novel in order. 18. Having read the novel, would you call the community a utopia or a dystopia (a malfunctioning utopia in which conditions are inhumane and terrifying)? Give examples from the novel to support your opinion. If you thought it was a dystopia, at what point in the story did you realize that something was wrong in the community? 19. Write Chapter 24 (on your own paper). Describe what happens to the community after Jonas and Gabe escape. Use the same point of view as the author. Try to mimic the author’s style. 20. The story offers many different and complex themes about different topics: Memory The power and importance of language The needs of society versus the needs of The “truth shall set you free” the individual How to create a “just” society “Sameness” versus difference The power of music, art, and creativity Conformity versus obedience The value of freedom Security versus risks Choose one of the themes above and write one to two paragraphs, tracing the theme’s development in the novel. 21. Read the attached “Message from the Author” (Hand-out #6) and Lois Lowry’s Newbery Acceptance Speech (Hand-out #7). Please highlight and annotate these two documents in preparation for class discussions. Focus on how Lowry’s personal history—her “memories”—influenced the writing of the book and her decisions to become a writer. (6 points each) Sources: Literature Circle Guide: The Giver, © 2001 Perdita Finn, Scholastic Teaching Resources. The Giver by Lois Lowry, A Study Guide, © 2012 Kathleen M. Fischer, Learning Links A Teacher’s Resource for The Giver, © 1999 Part of the “Witnesses to History” Series Produced by Facing History and Ourselves & Voices of Love and Freedom 4 English I – Honors: Summer Reading HAND-OUT #1 A Reader’s Guide to Annotation “Marking and highlighting a text is like having a conversation with a book – it allows you to ask questions, comment on meaning, and mark events and passages you want to revisit. Annotating is a permanent record of your intellectual conversation with the text.” (Laying the foundation: A Resource and Planning Guide for Pre-AP English) 5 As you work with your text, think about all the ways that you can connect with what you are reading. What follows are some suggestions that will help with annotating. ~Plan on reading most passages, if not everything, twice. The first time, read for overall meaning and impressions. The second time, read more carefully. Mark ideas, new vocabulary, etc. ~Begin to annotate. Use a pen, pencil, post-it notes, or a highlighter (although use it sparingly!). *Summarize important ideas in your own words. *Add examples from real life, other books, TV, movies, and so forth. *Define words that are new to you. *Mark passages that you find confusing with a ??? *Write questions that you might have for later discussion in class. *Comment on the actions or development of characters. *Comment on things that intrigue, impress, surprise, disturb, etc. *Note how the author uses language. A list of possible literary devices is attached. *Feel free to draw picture when a visual connection is appropriate *Explain the historical context or traditions/social customs used in the passage. ~Suggested methods for marking a text: *If you are a person who does not like to write in a book, you may want to invest in a supply of post it notes. *If you feel really creative, or are just super organized, you can even color code your annotations by using different color post-its, highlighters, or pens. *Brackets: If several lines seem important, just draw a line down the margin and underline/highlight only the key phrases. *Asterisks: Place and asterisk next to an important passage; use two if it is really important. *Marginal Notes: Use the space in the margins to make comments, define words, ask questions, etc. *Underline/highlight: Caution! Do not underline or highlight too much! You want to concentrate on the important elements, not entire pages (use brackets for that). *Use circles, boxes, triangles, squiggly lines, stars, etc. The Giver by Lois Lowry: Summer Reading HAND-OUT #2 Introduction to the Novel. The Giver has been a favorite of teenagers (and adults, and plenty of younger kids) for twenty years now. While dystopian novels have been around forever, Lois Lowry’s novel unquestionably paved the way for The Hunger Games, Above, Feed, The Eleventh Plague, and a dozen other scary-future yarns. 6 The Giver is a book that inspires passionate feelings. Many readers have loved it. The book has been praised in reviews and was awarded the Newbery Medal in 1993. Yet, The Giver has also been one of the most frequently censored books in the United States. It has been pulled off library shelves and forbidden in schools; it has been criticized for being too American and not American enough, too hopeless and too hopeful. Author Lois Lowry has said that readers create their own book, “bringing to the written words their own experiences, dreams, wishes, passions.” However students relate to it, The Giver is a thought-provoking book. This fascinating novel is about a boy names Jonas who lives in a nameless community sometime in the future with no war, poverty, hate, fear, pollution, or disease—a utopian life. It is a world by itself with no choices at all. Each aspect of life has a prescribed rule: one-year-olds—“Ones”—are named and given to their chosen family; “Nines” get their bicycles; “Birthmothers” give birth to three children first and then become laborers; “family units” get two children—one male and one female. Jonas is anxiously awaiting his Ceremony of Twelve, the time when all the twelve-year-olds in the community receive their assignments for their lifelong professions. The Giver by Lois Lowry: Summer Reading HAND-OUT #3 7 The Utopian Novel For thousands of years, writers and philosophers have been imagining how the world might be organized so people could live together more harmoniously. In the sixteenth century, just as the Europeans were discovering a New World in America, an Englishman named Thomas More wrote Utopia, a book about an ideal society. Utopia is a word More created from two Greek words—eu, which means “not,” and topia, which means “place.” So, literally, utopia means “not a place.” The word eu can also mean “good.” More seems to be saying two things at one: This is a good place, but it is also no place—it doesn’t exist. Since the publication of More’s book, utopia has come to mean a place that is ideal or perfect. Some of More’s ideas came from his reading of other ancient Greeks, and one of the books he surely read was Plato’s Republic, written in the fourth century B.C. In Plato’s ideal state, everyone shares equally in the community’s wealth, although there are three very different groups or classes of people. Workers farm and perform various trades; Auxiliaries have military responsibilities; and Guardians rule and advise everyone else. In The Republic, Plato explains that he is more interested in what is good for the community that what is good for the individual. “We are forming a happy state,” Plato writes, “not picking out some few persons to make them alone happy.” In our own century, however, several writers have raised questions about what living in such utopias might really be like for the individual. The dictators of World War II—Hitler, Mussolini, Franco, and Stalin—surely influenced Orwell. Orwell, an Englishman, did not believe that a place where every aspect of life was predetermined by the government would be in any way desirable. In 1984 (published in 1949), he describes a colorless state called Oceania. As in Plato’s Republic, Oceania has three classes of society—the Inner Party, the Outer Party, and the Proles. And as in More’s Utopia, private conversations are not allowed, and communication is monitored and controlled by ever-present video cameras. “Big Brother Is Always Watching You” proclaim posters on all the walls, and the Thought Police can practically read people’s minds. In Oceania no one can be trusted. Where George Orwell explored the dangers of political utopianism, another writer of the same period, Aldous Huxley, looked at the scientific and technological control over people’s lives. In Brave New World (published in 1932), he wrote about a frightening utopia call the World State. These writers were as interested in the worlds they lived in as they were in the ones they created in their imaginations. Their books were a way of thinking about what was wrong and what was right about their own societies. As you read The Giver, you will discover that Lowry is familiar with these authors and has been influenced by their work. She also has very particular things to say about our modern world. What concerns does Lowry have about our society? What does she value? 8 The Giver by Lois Lowry: Summer Reading HAND-OUT #4 The Oral Tradition Long before there was the written word people told stories to one another. The stories they loved and that mattered to them most were told again and again. Young children memorized the stories and told them to their children. Often the most important person in the community was the storyteller. That person knew all the stories, the myths and folktales that guided people in living their lives, the poems for celebrations and for funerals, and the jokes and riddles. Stories were told not only for pleasure for also for instruction. As people listened, they learned about famous men and women of the past and about the gods they believed created their world. These stories were their history, science, and religion. In ancient Greece, the storytellers would travel from community to community carrying their harps, often accompanied by a young person who had been chosen to learn all the storyteller knew. Homer, who composed the Iliad and the Odyssey (the stories of the fall of Troy and the wanderings of Odysseus) was a storyteller. He may have combined and added to many existing short songs and poems to create his epics. The audience was often involved in the stories, answering questions, calling out their own parts. Frequently, stories were sung and accompanied by music. In fact, the Greek word for storyteller, aidos, means “singer.” In many traditional societies, stories are still being told that have come down from one storyteller to another for over a thousand years. With the accessibility of books and the advent of electricity, however, people in modern cultures have become less interested in and have less time for the old stories. Still, as jokes get passed around from one friend to another, and a grandmother tells her grandchildren once more about how her own grandmother came to this country, we maintain our connection to the oral tradition. Interestingly, Lois Lowry was inspired to write The Giver while caring for her father who had lost much of his long-term memory. She began to imagine a society in which the past was deliberately forgotten. What would it be like? What happens when we are no longer sitting around together listening to the old stories? As you read, notice the ways the old man is like a traditional storyteller. 9 The Giver by Lois Lowry: Summer Reading HAND-OUT #5 The Hero’s Journey Odysseus, Theseus, Perseus—the great heroes of Greek mythology fought different monsters—the Cyclops, the Minotaur, and Medusa, respectively—and returned after many adventures to rule over different lands. In many ways, however, each hero took the same journey. In fact, says Joseph Campbell, author of The Hero with a Thousand Faces, if you look at stories from all over the world, you’ll find heroes always taking the same journey. The details are different, but the basic pattern is the same. In mythology a pattern that never changes is called an archetype. Almost always, from the moment of birth, the hero is marked as different from everybody else. A hero’s parents may be royal or even gods, but usually the hero doesn’t know this, for these are not the people who raise him or her. Hercules is raised by Amphitryton and Alcmene instead of his real parents, Zeus and Hera. In the movie Star Wars, Luke Skywalker grows up with his aunt and uncle. At some point, however, it becomes clear that this young person is destined for greatness. He or she has special talents that are developed under the guidance of a mentor. Arthur had Merlin, and Luke Skywalker had ObiWan Kenobi. Often the hero undergoes great physical and mental trials. Finally, though, in order to prove himself or herself, the hero must leave the teacher and set out on a dangerous quest on behalf of others. A quest is literally a search for something. The ancient hero Gilgamesh went looking for the secret of immortality. Sir Galahad left Arthur’s Round Table in the hopes of finding the Holy Grail. Quite often the task seems impossible. The hero almost always encounters many difficulties and may journey to the underworld or to death and back before reaching the goal. Always, the hero’s unique abilities rescue him or her. Hercules has his strength, and Odysseus has his way with words. 10 Finally, having achieved the goal, the hero prepares to return home. Often that trip is just as hard as the original quest. Again and again, the hero’s character is tested. Upon return the hero is rewarded and usually becomes a rule or occupies a position of fame and honor. In literature the hero is almost always a boy becoming a man and assuming a leadership role in the community. Because women in many traditional societies were not allowed leadership roles (and were not often the storytellers), the stories are rarely about them. There are some notable exceptions, however, including Inanna, from the ancient Sumerian stories, who journeys to the underworld to rescue her beloved. Jonas is, of course, in many ways following the traditional path of the hero. Think about how his experiences are similar to Luke Skywalker’s, Theseus’s, or Jason’s. You may want to watch Star Wars or read one of the Greek myths and compare and contrast Jonas with one of these other heroes. The Giver by Lois Lowry: Summer Reading HAND-OUT #6 A Message from the Author Kids always ask what inspired me to write a particular book or how did I get an idea for a particular book, and often it's very easy to answer that because books, like the Anastasia books, come from a specific thing, some little event triggers an idea. But a book like The Giver is a much more complicated book and therefore it comes from much more complicated places--and many of them are probably things that I don't even recognize myself anymore, if I ever did. So it's not an easy question to answer. I will say that the whole concept of memory is one that interests me a great deal. I'm not sure why that is, but I've always been fascinated by the thought of what memory is and what it does and how it works and what we learn from it. And so I think probably that interest of my own and that particular subject was the origin, one of many, of The Giver. Why does Jonas take what he does on his journey? He doesn't have much time when he sets out. He originally plans to make the trip farther along in time and he plans to prepare for it better. But then because of circumstances, he has to set out in a very hasty fashion. So what he chooses is out of necessity. He takes food because he needs to survive and he knows that. He takes the bicycle because he needs to hurry and the 11 bike is faster than legs. And he takes the baby because he is going out to create a future. And babies always represent the future in the same way children represent the future to adults. And so Jonas takes the baby so the baby's life will be saved, but he takes the baby also in order to begin again with a new life. Many kids want a more specific ending to The Giver. Some write, or ask me when they see me, to spell it out exactly. And I don't do that. And the reason is because The Giver is many things to many different people. People bring to it their own complicated sense of beliefs and hopes and dreams and fears and all of that. So I don't want to put my own feelings into it, my own beliefs, and ruin that for people who create their own endings in their minds. I will say that I find it an optimistic ending. How could it not be an optimistic ending, a happy ending, when that house is there with its lights on and music is playing? So I'm always kind of surprised and disappointed when some people tell me that they think that the boy and the baby just die. I don't think they die. What form their new life takes is something I like people to figure out for themselves. And each person will give it a different ending. In answer to the people who ask whether I'm going to write a sequel, they are sometimes disappointed to hear that I don't plan to do that. But in order to write a sequel, I would have to say: this is how it ended. Here they are and here's what's happening next. And that might be the wrong ending for many, many people who chose something different. Of course there are those who could say I can't write a sequel because they die. That's true if I just said, Well, too bad, sorry, they died there in the snow, therefore that's the end, no more books. But I don't think that. I think they're out there somewhere and I think that their life has changed and their life is happy and I would like to think that's true for the people they left behind as well. --Lois Lowry The Giver by Lois Lowry: Summer Reading HAND-OUT #7 Newbery Acceptance Speech Lois Lowry June 1994 12 “How do you know where to start?” a child asked me once, in a schoolroom, where I’d been speaking to her class about the writing of books. I shrugged and smiled and told her that I just start wherever it feels right. This evening it feels right to start by quoting a passage from The Giver, a scene set during the days in which the boy, Jonas, is beginning to look more deeply into the life that has been very superficial, beginning to see that his own past goes back farther than he had ever known and has greater implications than he had ever suspected. “…now he saw the familiar wide river beside the path differently. He saw all of the light and color and history it contained and carried in its slow-moving water; and he knew that there was an Elsewhere from which it came, and an Elsewhere to which it was going.” Every author is asked again and again the question we probably each have come to dread the most: HOW DID YOU GET THIS IDEA? We give glib, quick answers because there are other hands raised, other kids in the audience waiting. I’d like, tonight, to dispense with my usual flippancy and glibness and try to tell you the origins of this book. It is a little like Jonas looking into the river and realizing that it carries with it everything that has come from an Elsewhere. A spring, perhaps, at the beginning, bubbling up from the earth; then a trickle from a glacier; a mountain stream entering farther along; and each tributary bringing with it the collected bits and pieces from the past, from the distant, from the countless Elsewheres: all of it moving, mingled, in the current. For me, the tributaries are memories, and I’ve selected only a few. I’ll tell them to you chronologically. I have to go way back. I’m starting 46 years ago. In 1948, I am eleven years old. I have gone with my mother, sister, and brother to join my father, who has been in Tokyo for two years and will be there for several more. We live there, in the center of that huge Japanese city, in a small American enclave with a very American name: Washington Heights. We live in an American style house, with American neighbors, and our little community has its own movie theater, which shows American movies; and a small church, a tiny library, and an elementary school, and in many ways it is an odd replica of a United States village. (In later, adult years I was to ask my mother why we had lived there instead of taking advantage of the opportunity to live within the Japanese community and to learn and experience a different way of life. But she seemed surprised by my question. She said that we lived where we did because it was comfortable. It was familiar. It was safe.) At eleven years old I am not a particularly adventurous child, nor am I a rebellious one. But I have always been curious. I have a bicycle. Again and again – countless times without my parents’ knowledge – I ride my bicycle out the back gate of the fence that surrounds our comfortable, familiar, safe American community. I ride down a hill because I am curious and I enter, riding down that hill, an unfamiliar, slightly uncomfortable, perhaps even unsafe … though I never feel it to be … area of Tokyo that throbs with life. It is a district called Shibuya. It is crowded with shops and people and theaters and street vendors and the day-to- day bustle of Japanese life. I remember, still, after all these years, the smells: fish and fertilizer and charcoal; the sounds: music and shouting and the clatter of wooden shoes and wooden sticks and wooden wheels; and the colors: I remember the babies and toddlers dressed in bright pink and orange and red, most of all, but I remember, too, the dark blue uniforms of the school children: the strangers who are my own age. I wander through Shibuya day after day during those years when I am 11, 12 and 13. I love the feel of it, the vigor and the garish brightness and the noise; all of such a contrast to my own life. 13 But I never talk to anyone. I am not frightened of the people, who are so different from me, but I am shy. I watch the children shouting and playing around a school, and they are children my age, and they watch me in return; but we never speak to one another. One afternoon I am standing on a street corner when a woman near me reaches out, touches my hair, and says something. I back away, startled, because my knowledge of the language is poor and I misunderstand her words. I think she has said, “Kirai des’” meaning that she dislikes me; and I am embarrassed, and confused wondering what I have done wrong; how I have disgraced myself. Then, after a moment, I realize my mistake. She has said, actually, “Kirei-des’.” She has called me pretty. And I look for her, in the crowd, at least to smile, perhaps to say thank you if I can overcome my shyness enough to speak. But she is gone. I remember this moment – this instant of communication gone awry – again and again over the years. Perhaps this is where the river starts. In 1954 and 1955 I am a college freshman, living in a very small dormitory, actually a converted private home, with a group of perhaps fourteen other girls. We are very much alike. We wear the same sort of clothes: cashmere sweaters and plaid wool skirts, knee socks, and loafers. We all smoke Marlboro cigarettes, and we knit—usually argyle socks for our boyfriends—and play bridge. Sometimes we study; and we get good grades because we are all the cream of the crop, the valedictorians and class presidents from our high schools all over the United States. One of the girls in our dorm is not like the rest of us. She doesn’t wear our uniform. She wears blue jeans instead of skirts, and she doesn’t curl her hair or knit or play bridge. She doesn’t date or go to fraternity parties and dances. She’s a smart girl, a good student, a pleasant enough person, but she is different, somehow alien, and that makes us uncomfortable. We react with a kind of mindless cruelty. We don’t tease or torment her, but we do something worse: we ignore her. We pretend that she doesn’t exist. In a small house of fourteen young women, we make on invisible. Somehow, by shutting her out, we make ourselves feel comfortable. Familiar. Safe. I think of her now and then as the years pass. Those thoughts—fleeting, but profoundly remorseful— enter the current of the river. In the summer of 1979, I am sent by a magazine I am working for to an island off the coast of Maine to write an article about a painter who lives there alone. I spend a good deal of time with this man, and we talk a lot about color. It is clear to me that although I am a highly visual person – a person who sees and appreciates form and composition and color – this man’s capacity for seeing color goes far beyond mine. I photograph him while I am there, and I keep a copy of his photograph for myself because there is something about his face – his eyes – which haunts me. Later, I hear that he has become blind. I think about him – his name is Carl Nelson – from time to time. His photograph hangs over my desk. I wonder what it was like for him to lose the colors about which he was so impassioned. Now and then I wish, in a whimsical way, that he could have somehow magically given me the capacity to see the way he did. A little bubble begins, a little spurt, which will trickle into the river. In 1989 I go to a small village in Germany to attend the wedding of one of my sons. In an ancient church, he marries his Margret in a ceremony conducted in a language I do not speak and cannot understand. But one section of the service is in English. A woman stands in the balcony of that old stone church and sings the words from the Bible: where you go, I will go. Your people will be my people. 14 How small the world has become, I think, looking around the church at the many people who sit there wishing happiness to my son and his new wife – wishing it in their own language as I am wishing it in mine. We are all each other’s people now, I find myself thinking. Can you feel that this memory, too, is a stream that is now entering the river? Another fragment, my father, nearing 90, is in a nursing home. My brother and I have hung family pictures on the walls of his room. During a visit, he and I are talking about the people in the pictures. One is my sister, my parents’ first child, who died young of cancer. My father smiles, looking at her picture. “That’s your sister,” he says happily. “That’s Helen.” Then he comments, a little puzzled, but not at all sad, “I can’t remember exactly what happened to her.” We can forget pain, I think. And it is comfortable to do so. But I also wonder briefly: is it safe to do that, to forget? That uncertainty pours itself into the river of thought which will become the book. 1991. I am in an auditorium somewhere. I have spoken at length about my book, Number the Stars, which has been honored with the 1990 Newbery Medal. A woman raises her hand. When the turn for her question comes, she sighs very loudly and says, “Why do we have to tell this Holocaust thing over and over? Is it really necessary?” I answer her as well as I can – quoting, in fact, my German daughter-in-law, who has said to me, “No one knows better than we Germans that we must tell this again and again.” But I think about her question – and my answer – a great deal. Wouldn’t it, I think, playing Devil’s Advocate to myself, make for a more comfortable world to forget the Holocaust? And I remember once again how comfortable, familiar and safe my parents had sought to make my childhood by shielding me from ELSEWHERE. But I remember, too, that my response had been to open the gate again and again. My instinct had been a child’s attempt to see for myself what lay beyond the wall. The thinking becomes another tributary into the river of thought that will create The Giver. Here’s another memory. I am sitting in a booth with my daughter in a little Beacon Hill pub where she and I often have lunch together. The television is on in the background, behind the bar, as it always is. She and I are talking. Suddenly I gesture to her. I say, “Shhhh” because I have heard a fragment of the news and I am startled, anxious, and want to hear the rest. Someone has walked into a fast-food place with an automatic weapon and randomly killed a number of people. My daughter stops talking and waits while I listen to the rest. Then I relax. I say to her, in a relieved voice, “It’s all right. It was in Oklahoma.” (Or perhaps it was Alabama. Or Indiana.) She stares at me in amazement that I have said such a hideous thing. How comfortable I made myself feel for a moment, by reducing my own realm of caring to my own familiar neighborhood. How safe I deluded myself into feeling. I think about that, and it becomes a torrent that enters the flow of a river turbulent by now, and clogged with memories and thoughts and ideas that begin to mesh and intertwine. The river begins to seek a place to spill over. When Jonas meets The Giver for the first time, and tries to comprehend what lies before him, he says, in confusion “I thought there was only us. I thought there was only now.” In beginning to write The Giver I created – as I always do, in every book – a world that existed only in my imagination – the world of “only us, only now.” I tried to make Jonas’s world seem familiar, comfortable, and safe, and I tried to seduce the reader. I seduced myself along the way. It did feel good, that world. I got rid 15 of all the things I fear and dislike; all the violence, prejudice, poverty, and injustice, and I even threw in good manners as a way of life because I liked the idea of it. One child has pointed out, in a letter, that the people in Jonas’s world didn’t even have to do dishes. It was very, very tempting to leave it at that. But I’ve never been a writer of fairy tales. And if I’ve learned anything through that river of memories, it is that we can’t live in a walled world, in an “only us, only now” world where we are all the same and feel safe. We would have to sacrifice too much. The richness of color and diversity would disappear; feelings for other humans would no longer be necessary. Choices would be obsolete. And besides, I had ridden my bike Elsewhere as a child, and liked it there, but had never been brave enough to tell anyone about it. So it was time. A letter that I’ve kept for a very long time is from a child who has read my book called Anastasia Krupnik. Her letter – she’s a little girl named Paula from Louisville, Kentucky – says: I really like the book you wrote about Anastasia and her family because it made me laugh every time I read it. I especially liked when it said she didn’t want to have a baby brother in the house because she had to clean up after him every time and change his diaper when her mother and father aren’t home and she doesn’t like to give him a bath and watch him all the time and put him to sleep every night while her mother goes to work… Here’s the fascinating thing: Nothing that the child describes actually happens in the book The child – as we all do – has brought her own life to a book. She has found a place, a place in the pages of a book, that shares her own frustration and feelings. And the same thing is happening – as I hoped it would happen – with The Giver. Those of you who hoped that I would stand here tonight and reveal the “true” ending, the “right” interpretation of the ending, will be disappointed. There isn’t one. There’s a right one for each of us, and it depends on our own beliefs, our own hopes. Let me tell you a few endings which are the “right” endings for a few children out of the many who have written to me. From a sixth grader: “I think that when they were traveling they were traveling in a circle. When they came to “Elsewhere” it was their old community, but they had accepted the memories and all the feelings that go along with it…” From another: “…Jonas was kind of like Jesus because he took the pain for everyone else in the community so they wouldn’t have to suffer. And, at the very end of the book, when Jonas and Gabe reached the place that they knew as Elsewhere, you described Elsewhere as if it were heaven.” And one more: “A lot of people I know would hate that ending, but not me. I loved it. Mainly because I got to make the book happy. I decided they made it. They made it to the past. I decided the past was our world, and the future was their world. It was parallel worlds.” Finally, from one seventh grade boy: “I was really surprised that they just died at the end. That was a bummer. You could of made them stay alive, I thought.” Very few find it a bummer. Most of the young readers who have written to me have perceived the magic of the circular journey. The truth that we go out and come back, and that what we come back to is changed, and so are we. Perhaps I have been traveling in a circle too. Things come together and become complete. 16 Here is what I’ve come back to: The daughter who was with me and looked at me in horror the day I fell victim to thinking we were “only us, only now” (and that what happened in Oklahoma, or Alabama, or Indiana didn’t matter) was the first person to read the manuscript of The Giver. My son, and Margret, his German wife – the one who reminded me how important it is to tell our stories again and again, painful though they often are – now have a little girl who will be the receiver of all of their memories. Their daughter had crossed the Atlantic three times before she was six months old. Presumably my granddaughter will never be fearful of Elsewhere. Carl Nelson, the man who lost colors but not the memory of them, is the face on the cover of this book. He died in 1989 but left a vibrant legacy of paintings. One hangs now in my home. And I am especially happy to stand here tonight, on this platform with Allen Say because it truly brings my journey full circle. Allen was twelve years old when I was. He lived in Shibuya, that alien Elsewhere that I went to as a child on a bicycle. He was one of the Others, the Different, the dark-eyed children in blue school uniforms, and I was too timid then to do more than stand at the edge of their school yard, smile shyly, and wonder what their lives were like. Now I can say to Allen what I wish I could have said then: Watashi-no comodachi des’. Greetings, my friend. I have been asked whether the Newbery Medal is, actually, an odd sort of burden in terms of the greater responsibility one feels. Whether one is paralyzed by it, fearful of being able to live up to the standards it represents. For me the opposite has been true. I think the 1990 Newbery freed me to risk failure. Other people took that risk with me, of course. One was my editor, Walter Lorraine, who has never to my knowledge been afraid to take a chance. Walter cares more about what a book has to say than he does about whether he can turn it into a stuffed animal or a calendar or a movie. The Newbery Committee was gutsy too. There would have been safer books. More comfortable books. More familiar books. They took a trip beyond the realm of sameness, with this one, and I think they should be very proud of that. And all of you, as well. Let me say something to those of you here who do such dangerous work. The man that I named The Giver passed along to the boy knowledge, history, memories, color, pain, laughter, love, and truth. Every time you place a book in the hands of a child, you do the same thing. It is very risky. But each time a child opens a book, he pushes open the gate that separates him from Elsewhere. It gives him choices. It gives him freedom. Those are magnificent, wonderfully unsafe things. I have been greatly honored by you now, two times. It is impossible to express my gratitude for that. Perhaps the only way, really, is to return to Boston, to my office, to my desk, and to go back to work in hopes that whatever I do next will justify the faith in me that this medal represents. There are other rivers flowing. 17 18