An empirical look at the Defense Mechanism Test (DMT): Reliability

advertisement

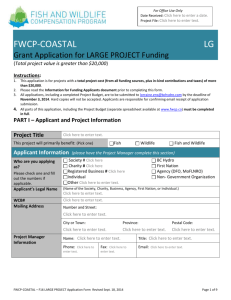

Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 2005, 46, 285–296 An empirical look at the Defense Mechanism Test (DMT): Reliability and construct validity Blackwell Publishing, Ltd. BO EKEHAMMAR,1 IRENA ZUBER2 and MARJA-LIISA KONSTENIUS3 1 Department of Psychology, Uppsala University, and Stockholm School of Economics, Sweden The Office of Cognitive Psychotherapy, Stockholm, Sweden 3 Department of Psychology, Stockholm University, Sweden 2 Ekehammar, B., Zuber, I. & Konstenius, M.-L. (2005). An empirical look at the Defense Mechanism Test (DMT): Reliability and construct validity. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 46, 285–296. Although the Defense Mechanism Test (DMT) has been in use for almost half a century, there are still quite contradictory views about whether it is a reliable instrument, and if so, what it really measures. Thus, based on data from 39 female students, we first examined DMT inter-coder reliability by analyzing the agreement among trained judges in their coding of the same DMT protocols. Second, we constructed a “parallel” photographic picture that retained all structural characteristic of the original and analyzed DMT parallel-test reliability. Third, we examined the construct validity of the DMT by (a) employing three self-report defense-mechanism inventories and analyzing the intercorrelations between DMT defense scores and corresponding defenses in these instruments, (b) studying the relationships between DMT responses and scores on trait and state anxiety, and (c) relating DMT-defense scores to measures of self-esteem. The main results showed that the DMT can be coded with high reliability by trained coders, that the parallel-test reliability is unsatisfactory compared to traditional psychometric standards, that there is a certain generalizability in the number of perceptual distortions that people display from one picture to another, and that the construct validations provided meager empirical evidence for the conclusion that the DMT measures what it purports to measure, that is, psychological defense mechanisms. Key words: DMT, projective techniques, defense mechanisms, construct validity. Bo Ekehammar, Department of Psychology, Uppsala University, Box 1225, SE-75142 Uppsala, Sweden . E-mail: bo.ekehammar@psyk.uu.se INTRODUCTION The Defense Mechanism Test (DMT) is a percept-genetic (cf. Kragh & Smith, 1970) and projective test based on assumedly anxiety-provoking TAT-like pictures, which are exposed through a tachistoscope using gradually increasing exposure duration ranging from 5 ms (subliminal) to 2,000 ms (supraliminal). The probably most often employed DMT picture (cf. Olff, 1991) depicts in the centre a teenage person (the Hero, in DMT terminology) of the same sex as the person being tested, and in the periphery an older and threatening person (the Peripheral person, in DMT terminology), of the same sex as the Hero and the person being tested. This situation is meant to depict an Oedipal threat (an angry mother or father) which is supposed to induce different types of “precognitive defensive organization” (Kragh, 1962a) and activate defense mechanisms characteristic of the perceiver. The DMT was originally developed by Kragh (1955) and has since then been employed for selection, especially in military settings (e.g., Kragh, 1960, 1962b; Harsveld, 1991; Neuman, 1978; Stoker, 1982; Stoll & Meier-Civelli, 1991; Torjussen & Værnes, 1991; Værnes, 1982), and for diagnosis in clinical contexts as well (e.g., Armelius, Sundbom, Fransson & Kullgren, 1990; Bogren & Bogren, 1999; Fransson & Sundbom, 1997; Jönsson, 1998; Rubino, Pezzarossa & Grasso, 1991; Sundbom & Armelius, 1992; Sundbom, Binzer & Kullgren, 1999). The rationale of the DMT as a selection instrument for stressful occupations is that the psychological defenses bind psychic energy necessary for coping with stressful situations, and further, the defenses give rise to perceptual distortions that make adequate perception in dangerous situations difficult (cf. Kragh, 1985). It should be emphasized that the DMT has been employed in different ways as regards apparatus, stimulus pictures, number of exposures and exposure times, instructions, followup questions, and evaluation of the DMT protocols (see Olff, 1991, for a review). Further, whereas the original DMT (cf., Kragh, 1985) is based on the classification of people’s responses into various psychoanalytical defenses, some recent attempts have been made to analyze DMT data without making such a classification but to base the analysis on the empirical structure of naturally occurring response categories. Thus, Cooper and Kline (1989; see also Cooper, 1991) have developed an “objectively scored” variant of the DMT that rests on G-analysis to assess the similarity between people’s response profiles as well as a Q-factor analysis of these person similarity measures to obtain person factors rather than factors based on correlations among variables. In a similar vein, Armelius and Sundbom (1991, see also Henningsson, Sundbom, Armelius & Erdberg, 2001) have employed partial least squares principal component and discriminant analysis to map people into a multidimensional space on the basis of their original DMT responses. In the present study, however, we have used procedures in line with the original methodology as expressed in Kragh’s (1985) official DMT manual. © 2005 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA. ISSN 0036-5564. 286 B. Ekehammar et al. Although the DMT has been in use for almost half a century, there are still conflicting opinions about its reliability and validity. For example, Harsveld (1991, p. 51) concluded that “the DMT is an extremely unreliable measuring instrument” and Stoll and Meier-Civelli (1991) stated that “the DMT as a whole is not convincing . . . there remain too many open questions and uncertainties” (p. 94), and further, “there are also problems with reliability of the test” (p. 95). On the contrary, Cooper (1988, p. 381) stated that it is “the most elegant and best-validated technique that exists for the study of defense mechanisms in normal and neurotic persons”, and Kline (1987) concluded that “the DMT is a reliable test in a wide variety of samples. It is clear that the DMT is a useful test both in clinical and occupational practice, and as a purported measure of defenses it should be valuable in theoretical research” (pp. 54–55). However, Kline (1987, 1993) also points out that the good predictive validity figures associated with the DMT, obtained in Scandinavian military selection settings, do not give any basis for the conclusion that DMT measures what it is supposed to measure (“it works but for wrong reasons”). Further, some non-Scandinavian military selection studies provide no empirical evidence at all for the DMT’s predictive validity (e.g., Harsveld, 1991; Stoker, 1982; Stoll & Meier-Civelli, 1991). Finally, Olff, Godaert, Brosschot, Weiss and Ursin (1990, 1991) failed to obtain significant correlations between DMT defenses and corresponding defenses measured by some other methods. In a previous study (Zuber & Ekehammar, 1997) based on a non-clinical sample, we examined the effects of various stimulus factors of the DMT by analyzing where the DMTdefense signs occur (distribution in exposure duration), which part of the picture that is involved (distribution in location), and which signs that co-occur (using correlation and factor analyses). The results disclosed, among other things, that the location of misperceptions to the central or the peripheral person of the picture was the major explanatory principle for the distribution of “signs of defense” on factors, rather than similarity according to some known criteria of psychodynamic theory. Instead of capturing psychodynamic defense mechanisms, which is the theoretical basis of the test, these results imply that DMT primarily tends to measure misperceptions linked to the stimulus picture and to general perceptual or information-processing characteristics of the perceiver. Some critical remarks of this study and its conclusions made by Kragh (1998, 2001) have been responded to by Ekehammar and Zuber (1999). In a more recent DMT study (Ekehammar, Zuber & Simonsson Sarnecki, 2002), we tested the basic psychodynamic proposition of the DMT by having the original DMT pictures redrawn without changing their structural properties, and in this way a friendly and a neutral DMT variant were shaped. In contrast to predictions made from psychodynamic/DMT theory, that the threatful variant would activate more “signs of defense” than the others, our results Scand J Psychol 46 (2005) disclosed that the three pictures activated the same amounts of “signs of defense” and the same levels of various perceptual DMT thresholds. In line with the conclusions from our previous study, these results suggest that rather than capturing psychodynamic defense mechanisms the DMT seems to tap perceptual or information-processing difficulties in correct identification of brief stimulus exposures regardless of their emotional contents. Thus, irrespective of the content of a visual stimulus, people seem to differ in how quick or slow they are in their visual information processing of briefly presented stimuli. This view has received further support by some neuropsychological EEG studies by Eriksen, Nordby, Olff and Ursin (2000) who showed that when exposed to neutral sine-wave tones those classified as having high or low DMT defense “differ in basic neurophysiological mechanisms connected with the way these subjects orient to new stimuli” (p. 267). In conclusion, our interpretation is radically different from the psychoanalytical view on which the DMT is based, which presupposes that the stimulus must be anxiety-evoking in order to elicit psychological defenses which in turn may cause perceptual distortions and misperceptions of the stimulus. In the present study, our aim was to take a closer look at the DMT’s reliability and still another look at its construct validity. It is clear from the background and the citations given there that there are quite contradictory views about whether the DMT is a reliable measuring instrument, and if so, what it really measures. Further, as expressed by Stoll and Meier-Civelli (1991), among others, there is some doubt about the positive DMT validity figures because most of them have been obtained in studies carried out by persons involved in the DMT; “The most serious charge that can be raised against the DMT is the fact that good prognostic validity has only been found by few scientists, such as Kragh and Neuman as test authors and by Torjussen, Ursin and Vaernes. In view of the other inconsistencies this does not inspire confidence” (p. 95). Against the background of this claim, it seems worthwhile to conduct an independent examination of DMT reliability and construct validity, and at the same time provide confirmation or disconfirmation of the findings and conclusions of our previous studies (Zuber & Ekehammar, 1997; Ekehammar et al., 2002). Thus, in the present study, we first analyzed the reliability of the DMT by examining the agreement among three DMT-trained psychologists in their coding of the same DMT protocols (inter-coder reliability). Second, because a test-retest approach to reliability estimation does not seem feasible for an instrument like the DMT (if the picture has been consciously perceived once, it is not regarded useful for a re-test), we constructed a “parallel” photographic picture (employing amateur actors) that retained all structural characteristics of the original (parallel-test reliability or generalizability). Third, we examined the construct validity of the DMT by (1) employing three defense-mechanism instruments that, in contrast to the DMT, are known and used in © 2005 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. DMT reliability and validity 287 Scand J Psychol 46 (2005) an international context, and analyzing the intercorrelations between DMT defense scores and corresponding defenses in these instruments, (2) studying the relationships between DMT defense scores and scores on trait and state anxiety, and (3) relating DMT defense scores to measures of basic and instrumental self-esteem. The construct validations were based on fairly strict predictions that were deduced and formulated a priori for the relationships between the DMT defense scores and the scores on the other instruments employed. Thus, under (1) above, we conducted a classical construct validation in line with that of Olff et al. (1990, 1991) and predicted from our information processing view that there would be no relationships between DMT defense scores (= perceptual distortions, according to our view) and scores on corresponding defenses, or defenses of similar degree of maturity, obtained through the three other instruments. If the DMT measures defense mechanisms in a psychoanalytical sense (Kragh, 1985), the prediction would be that DMT defense scores correlate with corresponding defense scores obtained from the other instruments. Under (2) above, we predicted from our viewpoint no systematic relations of DMT defenses (i.e., perceptual distortions) with state and trait anxiety whereas the prediction from the DMT point of departure would be that there are either positive or negative relationships between DMT defenses and state and trait anxiety either because people with high anxiety levels need psychological defenses to reduce their anxiety (positive relation) or because people with effective defenses can keep their anxiety levels low (negative relation). Under (3) above, the information processing model predicts no systematic relations of DMT total scores with basic and instrumental self-esteem or their combination whereas the prediction from the defense mechanism perspective would be that (a) the total DMT defense score is negatively related to basic and positively related to instrumental self-esteem (see Ihilevich & Gleser, 1986; Turkat, 1978), and (b) the combination of high basic and low instrumental self-esteem (high genuine self-esteem according to Turkat, 1978) would relate to a low total DMT score whereas the combination of low basic and low instrumental self-esteem (low genuine self-esteem according to Turkat, 1978) would relate to a high total DMT score. METHOD Participants The participants were 39 female undergraduate psychology students in the age range 20–43 years (M = 24.5 years) who took part in the study voluntarily and in return for course credits. Original and photographic picture The original female version of the probably most often used DMT picture (cf. Olff, 1991) was employed, showing a girl (Hero) in her early teens sitting at a table in the centre of the picture. The girl has a neutral look but behind the girl to the right is a middle-aged woman (Peripheral person) with a grotesque and threatful look. This TAT-like picture is drawn. A “parallel” photographic version of this picture was arranged by letting two amateur actors, one young and one middle-aged woman, “play” the same scene as in the original DMT picture, with the same composition and approximately the same distances between Hero, Peripheral person and table, as in the original picture. Several photo shots were taken and that photograph was finally chosen which was judged by a small group of researchers and psychologists (n = 5) to be most similar to the original. In this way, the two pictures could be regarded to be parallel as to the psychological situation and could thus be assumed to trigger the same psychological defenses. On the other hand, the pictures were different as to form (drawing vs. photograph) and time (old-fashioned vs. modern) in order to avoid possible test-retest effects. General procedure The participants were greeted on arrival by a female psychologist trained in the DMT. Before the pictures were exposed, the participants were instructed to fill out a background information and a state-anxiety inventory (see further below). Then, the pictures were exposed to each participant individually and in accord with the DMT manual (Kragh, 1985). However, the number of exposures was 12 instead of 22 as suggested in the manual (see further below). The testing procedure took on the average around 30 min. to complete. After this first session, the participants filled out the stateanxiety inventory again as well as some other self-report inventories measuring trait anxiety, defense mechanisms, and self-esteem (see further below). This phase also took around 30 min. to complete. Then, the participants had a 5 min. pause in the same room after which the second picture was exposed as above. The presentation order of the original and photographic picture was balanced so that in the first test session half of the participants were exposed to the original and half to the photographic picture. The second test session took also around 30 min. to complete. The DMT Procedure. The two pictures were each exposed 12 times to each participant using a tachistoscope especially constructed for DMT use (see Kragh, 1985). The exposure duration was 5, 10, 17, 30, 55, 95, 165, 290, 500, 870, 1,150, and 2,000 ms, respectively. Thus, the number of exposures was the same as in the Kragh (1962a) and Cooper and Kline (1986) validation studies, but in contrast to their studies, the exposure duration was gradually increased in line with the DMT manual (Kragh, 1985). Further, in non-clinical samples, the number of exposures can preferably be reduced (cf. Olff, 1991) without losing important information but saving some time. The instruction told the participants to try to verbalize and make a drawing of what they had perceived after each exposure of the picture. Follow-up questions were used in case of unclear responses on the sex, age and mood of the person(s) perceived in the picture (see Kragh, 1985, p. II:8; Olff, 1991, p. 157). Defense categories. Ten different defense mechanisms were coded according to the DMT manual (Kragh, 1985, p. IV:3): 1 Repression (e.g., the stimulus persons have a quality of rigidity and inanimateness). 2 Isolation (e.g., hero and peripheral person are separated from each other in the field; parts of the configuration are excluded). 3 Denial (existence of threat is denied explicitly). © 2005 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 288 B. Ekehammar et al. 4 Reaction formation (the threat is turned into its opposite, a positive relation between hero and peripheral person). 5 Identification with the aggressor (hero is the threatening person). 6 Introaggression (turning against the self, e.g., hero is sad, hurt or worthless). 7 Introjection of opposite sex (incorrect sex of hero/peripheral person). 8 Introjection of another object (incorrect age of hero/peripheral person). 9 Projection (successive changes of hero before peripheral person has become threatening). 10 Regression (the structure breaks down to a structure of an earlier phase level). Coding. The DMT protocols were coded and scored blindly in accord with the DMT manual (Kragh, 1985) by a second psychologist trained in DMT scoring. For each defense category, an unweighted sum of the number of signs of defense was computed as well as a weighted sum. The weights were assessed after having divided the number of exposures into three phases of equal length, starting with the exposure where the participant could report something meaningful for the first time (P1). The number of signs in each phase was multiplied with 1, 2 or 3 depending on their occurrence in the early, middle or late phase, respectively. In addition, a sum of the unweighted and weighted scores were computed across all defense categories to make up a total “defense” score. Further, three detection thresholds (measured in ms) were coded: P1 for the first meaningful percept, T1 for the first time the threat was reported, and C1 for the first correct perception of the major contents of the picture (cf. Kragh, 1985). Additional coders. To make possible estimates of the magnitude of inter-coder reliability, another two coders (one researcher and one psychologist) trained in the DMT procedure made independent and blind codings of the protocols taken up by the first psychologist. For this part of the study, 15 protocols from the original DMT picture were randomly chosen for reliability estimation. Defense mechanism inventories Three different self-report defense mechanism inventories were employed after translation to Swedish. Defense Mechanism(s) Inventory (DMI). The DMI is the most widely used self-report defense mechanism instrument (Davidson & McGregor, 1998) and was originally developed by Gleser and Ihilevich (1969). Reliability and validity support for the method has been provided (Cooper & Kline, 1982; Cramer, 1988, 1991; Gleser & Ihilevich, 1969; Gleser & Sachs, 1973; Ihilevich & Gleser, 1971, 1986, 1995; Juni, 1982; Vickers & Hervig, 1981; but see Blacha & Fancher, 1977; Davidson & McGregor, 1998). The revised DMI version (Ihilevich & Gleser, 1986) employed here purports to measure the relative intensity of five groups of psychological defenses assessed in five different conflict areas (authority, independence, competition, masculinity/femininity, situational) through ten brief stories, two for each conflict area. Each story is followed by four questions about the participant’s actual behavior, fantasy, thoughts, and feelings, respectively. A forced-choice response format is provided where five choices are given for each question, each corresponding to one of the five defenses being measured. The participant is instructed to choose one alternative that is most representative, and one that is least representative, of how he or she would react in the situation. The five defense categories coded are Turning Against Object (TAO; which includes identification with the aggressor and displacement), Projection (PRO), Principalization (PRN; which Scand J Psychol 46 (2005) includes intellectualization, rationalization, and isolation), Turning Against Self (TAS), and Reversal (REV; which includes denial, negation, reaction formation, and repression). Defense Style Questionnaire (DSQ). This instrument is based on Vaillant’s (e.g., 1971) model of the hierarchy of defense mechanisms derived from psychodynamic theory. The DSQ was originally developed by Bond, Gardner, Christian, and Sigal (1983) and has received empirical verification from some validation studies (e.g., Bond, 1995; Bond & Vaillant, 1986; Bond, Perry & Gautier, 1989; Pollock & Andrews, 1989; Vaillant, Bond & Vaillant, 1986) but not from others (Perry & Hoglend, 1998; Spinhoven, van Gaalen & Abraham, 1995; see also Davidson & McGregor, 1998). The revised DSQ (Bond, 1986, 1991) used in the present study contains 88 items that are constructed so as to catch the conscious derivatives of various defense categories. The item statements are responded to on 9-point scales anchored by 1 (strongly disagree) and 9 (strongly agree). The DSQ is focused on general defense styles rather than single defense mechanisms and has been found to be useful to differentiate between adaptive and maladaptive defense styles in the first hand (Bond, 1991). In the current use of the DSQ (e.g., Bond, Parris & Zweig-Frank, 1994), responses to the items are summed into the following defense styles: Factor 1 – Maladaptive Action Defenses (which include acting out, passive-aggression, regression, withdrawal, inhibition, projection); Factor 2 – Image-distorting Defenses (which include splitting, omnipotence, primitive idealization); Factor 3 – Self-sacrificing Defenses (which include pseudoaltruism, reaction formation); and Factor 4 – Adaptive Defenses (which include humour, suppression, sublimation). Life Style Index (LSI). This instrument was originally developed by Plutchik, Kellerman, and Conte (1979), and it is based on Plutchik’s (e.g., 1980) theory of emotion. The LSI is built on the conception (Plutchik, 1995; Plutchik et al., 1979) that different emotions are linked to specific defense mechanisms, for example, displacement is related to anger, compensation to sorrow, etc. According to this theory, defense mechanisms are unconscious per se but will be reflected in people’s reports of their emotions. An elaborated circumplex model has been presented by Conte and Plutchik (1993), where the relation between defense mechanisms, emotions, and personality disorders is specified. The revised version of LSI (Plutchik & Conte, 1989) was employed here, consisting of 97 items to which the participant has to respond whether the item statement applies to him or her ( yes) or not (no). The LSI covers eight defense categories: Denial, Reaction formation, Projection, Displacement, Repression, Regression, Compensation, and Intellectualization. The empirical support for the LSI has been somewhat contradictory as regards reliability and validity (cf. Conte & Plutchik, 1993; Davidson & McGregor, 1998; Endresen, 1991; Olff & Endresen, 1991; Plutchik et al., 1979). State and trait anxiety scales To examine participants’ degree of state anxiety, a new scale was constructed for the present study. It was based on two previous scales: (1) a Swedish version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger, Gorsuch & Lushene, 1970) presented by Rosén (1988) and comprising 20 items, and (2) the trait-anxiety scale of the Karolinska Scale of Personality (KSP; Schalling, 1986), from which 17 items were selected and modified so as to express state instead of trait anxiety. The 37 items of the state-anxiety inventory were answered to on a 4-point scale, anchored by 1 (do not agree at all) and 4 (agree completely). Scores were computed as unweighted sums across items for the three subscales Somatic, Muscular, and Cognitive state anxiety as well as Total state anxiety. © 2005 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. DMT reliability and validity 289 Scand J Psychol 46 (2005) The participants’ trait anxiety level was measured using the 30item trait scale of the KSP (Schalling, 1986) having the same response format as the state-anxiety scale above. Scores on the subscales Somatic (10 items), Muscular (10 items), and Cognitive (10 items) trait anxiety as well as Total trait anxiety were computed as described for the state scale. Self-esteem scales Self-esteem was measured by an instrument containing two scales developed by Forsman and Johnson (1996) and validated by the same authors (Forsman & Johnson, 1996; Johnson, 1998; Johnson & Forsman, 1995). The present version of the instrument comprised 31 items (statements) responded to on 5-point scales anchored by 1 (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree). The two scales measure Basic self-esteem and Instrumental (Earning) self-esteem, respectively, where basic self-esteem refers to a basic sense of self-worth or trust that is independent of others’ opinions and reactions whereas instrumental (earning) self-esteem means that the person is dependent on the confirmation from others to maintain his or her selfesteem. This distinction parallels the distinction made by Turkat (1978) between genuine and defensive self-esteem. RESULTS Inter-coder reliability Fifteen randomly selected DMT protocols were coded independently by three raters (A, B and C) and the reliabilities were estimated based on the number of signs of defense given by the raters on each defense category. The reliabilities were computed as pairwise inter-coder correlations (productmoment coefficients), mean inter-coder correlation, Cronbach’s α (expressing the reliability of the three coders’ average scores), and intraclass correlation (expressing the expected reliability of one rater’s scores). For two DMT defense categories (Identification with aggressor and Regression) no reliability estimates could be computed because of non-variance in some of the coders’ scores. The estimated reliability coefficients are presented in Table 1 which shows that with one exception only (Isolation) the inter-coder reliabilities are quite satisfactory. Thus, with one DMT coder, one could expect to obtain reliabilities between 0.76 and 0.95 for all defense codings except for Isolation, where a level of 0.55 could be expected. Generalizability of DMT scores Comparing the original and photographic DMT picture. Table 2 displays descriptive statistics for the DMT-defense scores and total scores of the original and photographic picture and t-tests for the difference in defense scores between these pictures. As shown in Table 2 for both pictures, only three of the DMT-defense categories are coded rather frequently (Reaction formation, Introjection of opposite sex, Introjection of other object) whereas two are never or seldom used (Identification with aggressor, Regression), and the others are used infrequently. Of the single defense categories, three (Reaction formation, Introjection of opposite sex, Introjection of other object) of the four significant differences between pictures reveal that the photographic picture has triggered more signs of defense than the original DMT picture. Further, the total defense score, unweighted as well as weighted, shows a significantly higher level for the photographic than the original DMT. One explanation for these differences, apart from differences in anxiety-eliciting characteristics of the two pictures, might be found in the perceptual thresholds for each picture. Thus, the mean thresholds were computed and tested for significance by t-tests. The results revealed that for P1 (first meaningful percept, in ms) there was a significant (p < 0.001) difference between the original (M = 55.6, SD = 49.3) and photographic (M = 7.23, SD = 2.9) picture. Thus, the photographic picture allowed a faster perception of something meaningful which means that more signs of defense were possible to code for this picture across the remaining exposures as compared to the original picture. However, the other two thresholds (T1 and C1) showed no significant mean differences between pictures (t = −1.80 and −0.40, respectively) which means that perception of threat, and correct perception, were similar for the two DMT-picture variants. Table 1. Inter-coder reliabilities for the DMT defense categories based on data from three coders (A, B and C) expressed as pairwise (r) and mean (Mr) inter-coder correlations, Cronbach’s α, and intraclass correlations (ric ) Defense category rAB rAC rBC Mr α ric 1. 2. 3. 4. 6. 7. 8. 9. 0.83 0.34 0.94 0.77 0.79 1.00 0.94 0.78 0.81 0.92 0.94 0.79 0.81 0.98 0.97 0.78 0.67 0.50 1.00 0.81 0.88 0.98 0.97 1.00 0.77 0.58 0.96 0.79 0.83 0.99 0.96 0.85 0.91 0.78 0.97 0.92 0.92 0.99 0.98 0.95 0.76 0.55 0.91 0.78 0.92 0.89 0.95 0.86 Repression Isolation Denial Reaction formation Introaggression Introjection of opposite sex Introjection of another object Projection Note: Reliabilities for Defense no. 5 – Identification with aggressor and 10 – Regression could not be computed because of non-variance for some coder. © 2005 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 290 B. Ekehammar et al. Scand J Psychol 46 (2005) Table 2. Descriptive statistics for the original and the photographic DMT picture on each defense category and for total scores, and t-values for the difference between pictures Original picture Photographic picture Defense category M SD M SD t (42) 1. Repression 2. Isolation 3. Denial 4. Reaction formation 5. Identification with aggressor 6. Introaggression 7. Introjection of opposite sex 8. Introjection of another object 9. Projection 10. Regression Total, unweighted Total, weighted 0.13 0.33 0.18 1.26 0.03 0.59 1.00 2.23 0.15 0.00 5.90 11.46 0.41 1.18 0.56 1.37 0.16 0.85 1.64 3.00 0.37 0.00 4.38 9.40 0.10 0.44 0.28 2.92 0.00 0.10 4.95 6.08 0.05 0.00 15.03 24.21 0.38 0.72 0.76 2.17 0.00 0.31 3.20 4.57 0.22 0.00 5.74 10.95 0.27 −0.52 −0.89 −5.13** – 3.56* −6.72** −5.41** 1.67 – −9.38** −7.37** * p < 0.01, ** p < 0.001. A final analysis of the characteristics of the two pictures was carried out by comparing their effects on state anxiety. Thus, the difference in state-anxiety level before and after picture presentation was compared using dependent t-tests. The results disclosed that state anxiety, both general and specific, was higher for both pictures before than after presentation. For somatic anxiety, the before-after difference was statistically significant for both the original (t = 5.13, p < 0.001) and photographic (t = 3.99, p < 0.001) picture, which was also the case for the total state anxiety score (t = 3.13, p < 0.01 and t = 2.17, p < 0.05, respectively). Parallel-test reliability. By correlating the participants’ DMT scores on the original and photographic picture, an estimate of parallel-test reliability was obtained for each defense category and the total defense score (unweighted and weighted values) as well as for the perceptual thresholds (ms). The results are displayed in Table 3 and show low to moderate figures. On four (repression, introaggression, introjection of opposite sex, projection) of the eight defense categories, there were no significant relationships between the scores (weighted or unweighted) on the original and photographic picture. On two of the categories (isolation, denial), there was a positive and significant relation for either the unweighted or weighted scores, and on the remaining two defenses (reaction formation, introjection of another object), there was a positive and significant correlation for both the unweighted and weighted scores (with r varying between 0.37 and 0.44). The total defense scores (summed across all defense categories) disclosed a significant and fairly high (r = 0.51) correlation for the weighted but not for the unweighted scores. Finally, the various perceptual thresholds did not display any significant relationships between the two pictures. Looked upon as parallel-test reliabilities, none of the figures given in Table 3 can be regarded satisfactory. Table 3. Parallel-test reliabilities of the DMT defense categories, total scores, and perceptual thresholds (P1, T1, C1) obtained through correlations between data from the original and the photographic DMT picture Defense category/Threshold Unweighted Weighted 1. Repression 2. Isolation 3. Denial 4. Reaction formation 6. Introaggression 7. Introjection of opposite sex 8. Introjection of another object 9. Projection Total DMT score P1 T1 C1 −0.09 0.23 0.44** 0.44** 0.17 0.05 0.37* 0.22 0.30 0.27 −0.19 0.00 −0.09 0.36* 0.28 0.41** 0.15 0.29 0.42** 0.20 0.51** Note: Reliabilities for Defense no. 5 – Identification with aggressor and 10 – Regression could not be computed because of nonvariance in score distribution. P1 = threshold for first meaningful percept, T1 = threshold for perception of threat, C1 = threshold for correct perception of picture. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01. However, the weighted total score showed a certain generalizability from one picture to the other. Construct validity Correlations with scores from other defense-mechanism instruments. The various defense instruments analyzed here differ from each other in the number and character of defense mechanisms. Thus, not all DMT defense categories have an exact correspondence in the self-report instruments. Table 4 gives an overview of a reasonable classification of © 2005 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. DMT reliability and validity 291 Scand J Psychol 46 (2005) Table 4. Self-report defense categories in the Life Style Index (LSI), the Defense Mechanism Inventory (DMI), and the Defense Style Questionnaire (DSQ) corresponding to DMT defense categories Table 6. Correlations between DMT and Defense Style Questionnaire (DSQ) defenses DSQ Factor DMT LSI DMI DSQ Repression Isolation Denial Reaction formation Introaggression Projection Regression Total Repression Intellectualization Denial Reaction formation – Projection – Total – PRN REV REV TAS PRO – – – Factor – Factor Factor Factor Factor Total 2 3 1 1 1 Notes: PRN = Principalization, REV = Reversal, TAS = Turning Aggression against Self, PRO = Projection, Factor 1 = Maladaptive action defenses, Factor 2 = Image-distorting defenses, Factor 3 = Self-sacrificing defenses. Table 5. Correlations between DMT defense categories and corresponding (see Table 4) categories in the Life Style Index (LSI) and the Defense Mechanism Inventory (DMI) DMT LSI DMI Repression Isolation Denial Reaction formation Introaggression Projection Total 0.01 0.09 −0.08 0.01 – 0.13 −0.03 – −0.06 −0.03 0.18 0.25 −0.07 – Note: No correlations are significant at p < 0.05. which DMT-defense categories that correspond to which defense categories in the self-report instruments (DMI, LSI, DSQ). This classification was employed here to make possible an analysis of the convergent validity of the DMT. Table 5 shows the correlations (product-moment coefficients) of the DMT defenses with the corresponding LSI and DMI defenses. As displayed in the table, there were no significant (p < 0.05) correlations for the six DMT defenses that have a correspondence in the LSI or DMI. The largest correlation coefficient (r = .25, p < 0.10) was obtained for the relation between DMT and DMI Introaggression. The other ten relationships that were possible to compute were all close to zero and non-significant. In Table 6, the correlations (product-moment coefficients) between DMT and corresponding DSQ defenses are presented. In this case, because of a small number of corresponding categories, the defense categories have also been divided into mature (DMT defenses Repression, Isolation, Reaction formation; DSQ factors 1 and 2) and immature (the rest of the DMT defenses; DSQ factor 3) on the basis of psychodynamic theory (e.g., Kernberg, 1975). Thus, comparisons can be made between strictly corresponding categories as well as categories that should correspond on the basis DMT defense 1 2 3 4 Repression Isolation Denial Reaction formation Introaggression Introjection of opposite sex Introjection of other object Projection Total 0.13 −0.08 −0.21 0.07 0.20 0.31* 0.08 0.04 0.18 −0.01 0.02 0.01 −0.06 0.23 0.14 −0.01 0.28 0.14 0.02 0.34* 0.00 −0.10 0.05 0.17 0.06 0.20 0.26 0.11 −0.11 −0.04 0.07 0.10 −0.11 0.07 −0.10 0.04 Notes: Italicized figures denote coefficients for corresponding defenses, bold-face figures denote expected relations based on the degree of maturity of the defenses. * p < 0.05 (one-tailed). of degree of maturity. As shown in Table 6, none of the three correlations between strictly corresponding categories was statistically significant. Further, only two of the ten expected (provided that DMT measures defense mechanisms) relationships on the basis of degree of maturity displayed significant (p < 0.05) outcomes. Finally, the DMT total defense score did not show any significant relationship with any of the DSQ defense factors. Correlations with trait and state anxiety. The correlations of DMT scores with trait and state anxiety are presented in Table 7. As the subscores of the anxiety scales (somatic, muscular, cognitive) displayed the same correlational picture as the total anxiety scores, only the last-mentioned are given in the table. The state-anxiety correlations are based on those 20 participants who received the original DMT picture during the first test session, before and after which stateanxiety data were collected. As shown in Table 7, there was a positive but nonsignificant correlation of DMT total defense score with total trait anxiety but a significant and fairly substantial relationship with total state anxiety, before (r = 0.52) as well as after (r = 0.63) the DMT exposures. Further, of the eight correlations between the single DMT defenses and trait anxiety, there were two significant coefficients, which is more than expected by chance. Also, corresponding correlations for state anxiety showed more significant coefficients than expected by chance (three out of eight for the before and after measure, respectively). Thus, to sum up, one may conclude that there were some significant correlations of fairly substantial magnitude between DMT defense and state anxiety scores, which lends some support to the view that the DMT measures defense mechanisms (but see Discussion section). Correlations with self-esteem. The correlations (productmoment coefficients) of DMT defense scores with Basic and © 2005 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 292 B. Ekehammar et al. Scand J Psychol 46 (2005) Table 7. Correlations of DMT defenses with total trait and state anxiety (Before = before picture exposure, After = after picture exposure) State anxiety Defense category Trait anxiety Before After Repression 2. Isolation 3. Denial 4. Reaction formation 6. Introaggression 7. Introjection of opposite sex 8. Introjection of another object Projection Total score 0.29* −0.09 −0.20 −0.02 0.11 0.31* 0.21 −0.05 0.25 0.37* 0.12 −0.43* −0.17 0.16 0.28 0.53** 0.26 0.52** 0.33 0.05 −0.42* −0.29 0.37 0.52** 0.54** 0.30 0.63** Notes: Correlations for Defense no. 5 – Identification with aggressor and 10 – Regression could not be computed because of non-variance in score distribution. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 (one-tailed). Table 8. Correlations of DMT defenses with basic and instrumental self-esteem (SE) Defense category Basic SE Instrumental SE 1. Repression 2. Isolation 3. Denial 4. Reaction formation 6. Introaggression 7. Introjection of opposite sex 8. Introjection of another object Projection Total score −0.13 0.11 0.04 −0.11 0.19 −0.37* −0.06 0.19 −0.18 0.34* 0.05 0.02 −0.03 −0.02 −0.06 −0.20 −0.11 −0.13 Notes: Correlations for Defense no. 5 – Identification with aggressor and 10 – Regression could not be computed because of nonvariance in score distribution. * p < 0.01 (one-tailed). Instrumental (Earning) self-esteem are given in Table 8. Provided that DMT measures defense mechanisms, the expectation was that the total DMT defense score would be negatively related to basic and positively related to instrumental self-esteem. However, the table shows that these two correlations were negative and non-significant. Further, as shown in Table 8, there were only two significant correlations between the single DMT defense categories and the two types of self-esteem, which could hardly have been predicted from the defense mechanism proposition. Rather, they might have occurred by chance. Further, the combination of basic and instrumental self-esteem (after median splits of the respective score distributions), which is the main idea when using the present instrument (cf. Johnson & Forsman, 1995), did not yield any significant outcome. Thus, we must conclude that no meaningful relationships between DMT and self-esteem scores were obtained. DISCUSSION The present study has examined various reliability and construct validity characteristics of the DMT. As to reliability, one of our analyses focused on inter-coder reliability, that is, the agreement among DMT-experienced coders’ ratings of the same DMT protocols. The results disclosed that this aspect of reliability was clearly satisfactory for all DMT defenses with only one exception. Thus, with the exception of the defense category Isolation, the reliability coefficients fell within the interval reported by Kragh (1985) in the DMT manual. However, this source does not give any clear description of how the reliability indices have been computed (but see, e.g., Ozolins, 1989). Anyhow, it seems clear that DMT-trained psychologists seem to achieve high agreement in their DMT ratings although it is quite obvious that for some defense categories (Introjection of opposite sex = incorrect sex of perceived person; Introjection of another object = incorrect age of perceived person), the criteria for coding are so objective that disagreement among judges is almost impossible. The implication of the high inter-coder reliability is that one basic aspect of DMT reliability is satisfied which would make it possible to detect latent relationships between DMT and other constructs. As test-retest reliability does not seem appropriate for a projective test like the DMT (e.g., Kragh, 1985), we examined parallel-test reliability instead. According to Kragh (1985, p. III:1), parallel-test reliability estimation “presents a viable alternative” to the test-retest method. “However, the pictures of the first and of the second (third, etc.) perceptgenesis should not be too similar, or we can expect the retest effect to come into play” (Kragh, 1985, p. III:1). The reliability coefficients for the eight single defenses that were possible to compute in our study showed figures between −0.09 and 0.44 whereas the total defense scores showed a somewhat higher agreement, 0.30 for the unweighted and 0.51 for the weighted scores. Corresponding values for the perceptual thresholds varied between −0.19 and 0.27. Looked upon as traditional parallel-test reliability estimates, these figures are clearly unsatisfactory and below standard psychometric requirements. However, if we have succeeded in following Kragh’s (1985) advice, that the versions “should not be too similar”, it can of course be questioned if we have succeeded in creating a “parallel” picture to the original in a strict psychometric sense. For example, the number of perceptual distortions (“signs of defense”) was substantially higher for the photographic than the original picture, and the threshold for the first meaningful percept was substantially lower. These findings go together because an early report of a meaningful percept in the series allows coding of more “signs of defense” (perceptual distortions) in the subsequent exposures. However, differences between the pictures in these respects will not necessarily affect the magnitude of the correlation coefficients which, for the reasons given, could perhaps be labeled generalizability instead of reliability coefficients. © 2005 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. DMT reliability and validity 293 Scand J Psychol 46 (2005) Anyhow, there was a certain degree of agreement in the participants’ total defense scores (number of misperceptions) between pictures, especially when these were weighted on the basis of where in the series (early or late) the misperceptions occurred (late misperceptions are weighted more heavily than early ones). Looking at previous DMT research, we could find only one study (Harsveld, 1991) similar to ours on this point. In a pilot-selection setting, Harsveld (1991) computed, among other things, correlations between “signs of defense” for the present (but male) original DMT picture and a second (male) “parallel” picture included in the TAT package. The correlations obtained between the two pictures for the various defense categories were very similar to our figures, varying between 0.06 and 0.31 (no coefficients for total defense scores were computed), and Harsveld (1991) concluded that, “all measures discussed thus far are characterized by poor reliability. The mechanisms seem to be largely determined by factors outside the personality of the testee . . .” (p. 60). Our construct validation of the DMT defenses through examining their relationships with corresponding defense categories in three different defense-mechanism inventories yielded rather discouraging outcomes for the defense mechanism hypothesis. First, there were no significant relations between the total defense scores of the DMT and those of the other instruments. Second, there were no significant relations between any of the single DMT defense scores and the scores for corresponding defenses in the other three instruments. In fact, this outcome corresponds very well with the results of previous DMT studies by Olff et al. (1990, 1991) who examined the relationships between the DMT and two of the self-report defense instruments (DMI and LSI) also examined in our study: “The most striking finding of this study however is that there are no substantial correlations between the overall scores of the different defense questionnaires and the DMT. Also, there are no correlations between the corresponding subscales of the defense measures in DMT and those in the questionnaires” (Olff et al., 1991, p. 314). Thus, our and Olff et al.’s (1990, 1991) examinations of the construct validity of the DMT seem to converge on all important points. Although there appears to be no relations between people’s responses to the DMT and their scores on various selfreport defense-mechanism questionnaires (which are correlated among themselves), it would be unfair to conclude that this finding definitely invalidates the DMT. In accord with classical psychometric thinking the conclusion would be that the DMT lacks construct validity. But the situation is complicated by the fact that recent research in various psychological domains (e.g., memory, motives, attitudes, prejudice) has made a distinction between explicit (slow, intentional, conscious) and implicit (fast, automatic, unconscious) aspects of the same phenomenon (see, e.g., Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). Further, empirical studies on this issue show that implicit and explicit measures of the same construct are not necessarily associated. As just one example, and of relev- ance in the present context, McClelland, Koestner, and Weinberger (1989) used projective TAT pictures (supposed to measure implicit processes) as well as self-report questionnaires (supposed to measure explicit processes) to study need-for-achievement and power motives among people. The results disclosed weak correlations between the implicit and explicit measures of the same motive and showed that the implicit and explicit motives were related to different kinds of external variables as well. The study of psychological defense mechanisms might benefit from a similar approach, that is, to examine the power of the implicit and explicit measures, respectively, for predicting various types of relevant external behaviors. In this way, a safer conclusion could be drawn as to the relative utility of the supposedly implicit (e.g., the DMT) and explicit (questionnaires) approaches to the study of defense mechanisms. It can be argued, however, that the processes involved in DMT perception are not fully implicit as all the exposures are not subliminal because of the increasing exposure duration up to 2,000 ms. Thus, quite a few DMT exposures are definitely supraliminal for almost all people, which makes possible cognitive elaboration of the stimulus and makes the process explicit (slow, intentional, conscious) rather than implicit. The conclusion is that the DMT is not easily classified as measuring either explicit or implicit processes. Then, one could argue that it is at least not possible to “fake good” in the DMT because the test person cannot be expected to know which answers are classified as defenses or not. However, the situation is more or less the same as concerns some of the self-report defense mechanism instruments. In the DMI, for example, after having read a vignette, the test person is instructed to answer questions about his or her actual reaction, thought, fantasy, and feeling. Also in this case, it seems improbable that the person could fake his or her answers in some direction to get or avoid a score on a specific defense mechanism. In conclusion, we mean that the similarities between the DMT and the defense mechanism questionnaires, as discussed above, make it reasonable to predict a certain correlation between the scores obtained from them, provided that the DMT actually measures defense mechanisms. In the construct validation employing measures on state and trait anxiety, we predicted no correlations whereas the defense mechanism view would predict positive or negative correlations of the participants’ total DMT defense scores with their state and trait anxiety levels. The results disclosed significant and fairly substantial relationships between DMT and total state anxiety, before (r = 0.52) as well as after (r = 0.63) the DMT exposures but there were no significant relations with total trait anxiety. Thus, the results indicate that people’s state-anxiety levels affect their DMT perceptions, the higher their state anxiety the larger is the number of perceptual distortions (“signs of defense”) in their DMT responses. Further, this relation seems to hold for their state anxiety observed before as well as after the DMT exposures. © 2005 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 294 B. Ekehammar et al. Thus, anticipatory anxiety or test anxiety seem to explain this finding rather than the anxiety-evoking character of the DMT picture. The final construct validation examined the relationships between DMT scores on the one hand and basic and instrumental self-esteem on the other. Our hypotheses were supported. Thus, people’s DMT defense scores do not seem to be meaningfully related to their basic and instrumental selfesteem levels. How do the present results fit into the picture obtained from our previous studies (Ekehammar et al., 2002; Zuber & Ekehammar, 1997) where we, in accord with some other researchers (e.g., Cooper & Kline, 1989; Eriksen, Olff, Mann, Sterman & Ursin, 1996; Eriksen et al., 2000; Stoll & Meier-Civelli, 1991), questioned the proposition that perceptual distortions in the test are reflections of defense mechanisms in a psychoanalytical sense. Instead, we suggested that the DMT seems to tap more general perceptual or informationprocessing difficulties in correct identification of brief stimulus exposures regardless of their emotional contents. First, the different construct validations sustained our previous view that the DMT does not catch defense mechanisms in a psychoanalytical sense because the expected relationships with other defense mechanism instruments, with trait anxiety, and with self-esteem did not show up. Second, there was a certain generality in the participants’ total number of perceptual distortions between the two pictures that we employed, but a low generality for specific “defenses”, which provides support to our contention that the DMT seems to reflect more general information-processing difficulties when trying to identify the content of brief stimulus exposures. Thus, these results fit rather nicely into our previous picture. In addition, the present results suggest that the perceiver’s state anxiety level affects the DMT responses; the higher the state anxiety the more perceptual distortions were observed. As explained above, anticipatory or test anxiety is a more plausible explanation to this finding rather than the anxietyevoking character of the DMT picture itself. That state anxiety interferes with information-processing quality is a well-known finding and might explain the relation between state anxiety and perceptual distortions in the DMT. As a final theoretical conclusion, we want to emphasize, like we did in our previous DMT study (Ekehammar et al., 2002), that the present findings do not contradict the view that there exist unconscious psychological processes in general. However, in line with the conclusions of Kihlstrom (1999) and others, our results suggest that the study of unconscious processes using subliminal and other techniques do not support psychoanalytical theory. Thus, in a review of experimental studies on the psychological unconscious, Kihlstrom (1999, p. 435) concluded that “(n)one of the experiments reviewed involve sexual or aggressive contents, none of their results imply defensive acts of repression, and none of their results support hermeneutic methods of interpreting manifest contents in terms of latent contents.” Scand J Psychol 46 (2005) The study was supported by grants to Bo Ekehammar from the Swedish Council for Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences (F617/94). The authors are obliged to Jeanette Wennergren and Sophia Marongiu Ivarsson for administrating the DMT. REFERENCES Armelius, B.-Å. & Sundbom, E. (1991). Hard and soft models for the assessment of personality organization by DMT. In M. Olff, G. Godaert & H. Ursin (Eds.), Quantification of human defence mechanisms (pp. 138–147). Berlin: Springer. Armelius, B.-Å., Sundbom, E., Fransson, P. & Kullgren, G. (1990). Personality organization defined by DMT and the Structural Interview. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 33, 81–88. Blacha, M. D. & Fancher, R. E. (1977). A content validity study of the Defense Mechanism Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 41, 402– 404. Bogren, L. & Bogren, I.-B. (1999). Early visual information processing and the Defence Mechanism Test in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 99, 460– 465. Bond, M. (1986). Defense Style Questionnaire. In G. E. Vaillant (Ed.), Empirical studies of ego mechanisms of defense (pp. 146– 152). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Bond, M. (1991). Manual for the Defense Style Questionnaire. Unpublished manuscript Bond, M. (1995). Development and properties of the Defense Style Questionnaire. In H. R. Conte & R. Plutchik (Eds.), Ego defense theory and measurement (pp. 202–220). New York: Wiley. Bond, M., Gardner, S. T., Christian, J. & Sigal, J. J. (1983). Empirical study of self-rated defense style. Archives of General Psychiatry, 40, 333 –338. Bond, M., Paris, J. & Zweig-Frank, H. (1994). Defense styles and borderline personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 8, 28–31. Bond, M., Perry, J. C. & Gautier, M. (1989). Validating the self-report of defense styles. Journal of Personality Disorders, 3, 101–112. Bond, M. & Vaillant, J. S. (1989). An empirical study of the relationship between diagnosis and defense style. Archives of General Psychiatry, 43, 285–288. Conte, H. R. & Plutchik, R. (1993). The measurement of ego defenses in clinical research. In U. Hentschel, G. J. W. Smith, W. Ehlers & J. G. Draguns (Eds.), The concept of defense mechanisms in contemporary psychology: Theoretical, research, and clinical perspectives (pp. 275 –289). New York: Springer. Cooper, C. (1988). The scientific status of the Defence Mechanism Test. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 61, 381–384. Cooper, C. (1991). G-analysis of the DMT. In M. Olff, G. Godaert & H. Ursin (Eds.), Quantification of human defence mechanisms (pp. 121–137). Berlin: Springer. Cooper, C. & Kline, P. (1982). A validation of the Defense Mechanism Inventory. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 55, 209–214. Cooper, C. & Kline, P. (1986). An evaluation of the Defence Mechanism Test. British Journal of Psychology, 77, 19–31. Cooper, C. & Kline, P. (1989). A new objectively scored version of the Defence Mechanism Test. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 30, 228 –238. Cramer, P. (1988). The Defense Mechanism Inventory: A review of research and discussion of the scales. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 142–164. Cramer, P. (1991). The development of defense mechanisms: Theory, research, and assessment. New York: Springer. Davidson, K. & MacGregor, M. W. (1998). A critical appraisal of self-report defense mechanism measures. Journal of Personality, 66, 965 –992. © 2005 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. DMT reliability and validity 295 Scand J Psychol 46 (2005) Ekehammar, B. & Zuber, I. (1999). In defence of the criticism of the Defence Mechanism Test (DMT): A reply to Kragh (1998). Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 40, 85 – 87. Ekehammar, B., Zuber, I. & Simonsson Sarnecki, M. (2002). The Defence Mechanism Test (DMT) revisited: Experimental validation using threatening and non-threatening pictures. European Journal of Personality, 16, 283 –294. Endresen, I. M. (1991). A Norwegian translation of the Plutchik questionnaire for psychological defense. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 32, 105 –113. Eriksen, H. R., Nordby, H., Olff, M. & Ursin, H. (2000). Effects of psychological defense on processing of neutral stimuli indicated by event-related potentials (ERPs). Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 41, 263–267. Eriksen, H. R., Olff, M., Mann, C., Sterman, M. B. & Ursin, H. (1996). Psychological defense mechanisms and electroencephalographic arousal. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 37, 351– 361. Forsman, L. & Johnson, M. (1996). Dimensionality and validity of two scales measuring different aspects of self-esteem. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 37, 1–15. Fransson, P. & Sundbom, E. (1997). Defense Mechanism Test (DMT) and Kernberg’s theory of personality organization related to adolescents in psychiatric care. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 38, 95 –102. Gleser, G. C. & Ihilevich, D. (1969). An objective instrument for measuring defense mechanisms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 33, 51– 60. Gleser, G. C. & Sacks, M. (1973). Ego defenses and reaction to stress: A validation study of the Defense Mechanisms Inventory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 40, 181–187. Greenwald, A. G. & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102, 4–27. Harsveld, N. (1991). The Defence Mechanism Test and success in flying training. In E. Farmer (Ed.), Stress and error in aviation (Vol. 1, pp. 51–65). Aldershot, UK: Avebury Technical. Henningsson, M., Sundbom, E., Armelius, B.-Å. & Erdberg, P. (2001). PLS model building: A multivariate approach to personality test data. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 42, 399–409. Ihilievich, D. & Gleser, G. C. (1971). Relationship of defense mechanisms to field dependence-independence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 77, 296 –302. Ihilievich, D. & Gleser, G. C. (1986). Defense mechanisms: Their classification, correlates, and measurement with the Defense Mechanisms Inventory. Owosso, MI: DMI Associates. Ihilievich, D. & Gleser, G. C. (1995). The Defense Mechanisms Inventory: Its development and clinical applications. In H. R. Conte & R. Plutchik (Eds.), Ego defenses: Theory and development (pp. 221–246). New York: Wiley. Johnson, M. (1998). Self-esteem stability: The importance of basic self-esteem and competence strivings for the stability of global self-esteem. European Journal of Personality, 12, 103–116. Johnson, M. & Forsman, L. (1995). Competence strivings and selfesteem: An experimental study. Personality and Individual Differences, 19, 417– 430. Jönsson, S. A. T. (1998). The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), but not the Defence Mechanism Test (DMTm), separates schizophrenics and normal controls in a factorial cluster analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 39, 109– 116. Juni, S. (1982). The composite measure of the Defense Mechanism Inventory. Journal of Research in Personality, 16, 193 –200. Kernberg, O. (1975). Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. New York: Aronson. Kihlstrom, J. F. (1999). The psychological unconscious. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality (2nd edn, pp. 424 – 442). New York: Guilford Press. Kline, P. (1987). The scientific status of the DMT. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 60, 53 –59. Kline, P. (1993). The Defence Mechanism Test in occupational psychology: A critical examination of its validity. European Review of Applied Psychology, 43, 197–204. Kragh, U. (1955). The actual-genetic model of perception-personality. Lund, Sweden: Gleerup. Kragh, U. (1960). The Defense Mechanism Test: A new method for diagnosis and personnel selection. Journal of Applied Psychology, 44, 303 –309. Kragh, U. (1962a). Precognitive defensive organisation with threatening and non-threatening peripheral stimuli. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 3, 65 – 68. Kragh, U. (1962b). Predictions of success of Danish attack divers by the Defense Mechanism Test. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 15, 303 –309. Kragh, U. (1985). The Defence Mechanism Test: Manual. Stockholm: Persona. Kragh, U. (1998). In defence of the Defence Mechanism Test: A reply. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 39, 123 –124. Kragh, U. (2001). DMT interminable: A re-reply to I. Zuber and B. Ekehammar. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 42, 135–136. Kragh, U. & Smith, G. (1970). Percept-genetic analysis. Lund, Sweden: Gleerup. McClelland, D. C., Koestner, R. & Weinberger, J. (1989). How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ? Psychological Review, 96, 690 –702. Neuman, T. (1978). Dimensionering och validering av perceptgenesens försvarsmekanismer: En hierarkisk analys mot pilotens stressbeteende. [Dimension analysis and validation of percept-genetic defence mechanisms: A hierarchical analysis of the pilot’s behaviour under stress.] (Report no. C55020-H6). Stockholm: FOA [National Defence Establishment, Division of Behavioural Sciences.] Olff, M. (1991). The DMT method in Europe: State of the art. In M. Olff, G. Godaert & H. Ursin (Eds.), Quantification of human defence mechanisms (pp. 148 –171). Berlin: Springer. Olff, M. & Endresen, I. M. (1991). The Dutch and the Norwegian translations of the Plutchik questionnaire for psychological defence. In M. Olff, G. Godaert & H. Ursin (Eds.), Quantification of human defence mechanisms (pp. 59 –71). Berlin: Springer. Olff, M., Godaert, G., Brosschot, J. F., Weiss, K. E. & Ursin, H. (1990). Tachistoscopic and questionnaire methods for the measurement of psychological defences. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 31, 89 –98. Olff, M., Godaert, G., Brosschot, J. F., Weiss, K. E. & Ursin, H. (1991). The Defence Mechanism Test related to questionnaire methods for measurement of psychological defence. In M. Olff, G. Godaert & H. Ursin (Eds.), Quantification of human defence mechanisms (pp. 302–320). Berlin: Springer. Ozolins, A. (1989). Defence patterns and non-communicative body movements. Stockholm: Almquist & Wiksell International. Perry, J. C. & Hoglend, P. (1998). Convergent and discriminant validity of overall defensive functioning. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 186, 529 –535. Plutchik, R. (1980). Emotion: A psychoevolutionary synthesis. New York: Harper & Row. Plutchik, R. (1995). A theory of ego defenses. In H. R. Conte & R. Plutchik (Eds.), Ego defenses: Theory and measurement (pp. 13– 37). New York: Wiley. Plutchik, R. & Conte, H. R. (1989). Measuring emotions and their derivates: Personality traits, ego defenses, and coping styles. In S. Wetzler & M. Katz (Eds.), Contemporary approaches to psychological assessment (pp. 241–269). New York: Brunner/Mazel. © 2005 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 296 B. Ekehammar et al. Plutchik, R., Kellerman, H. & Conte, H. R. (1979). A structural theory of ego defenses and emotions. In C. E. Izard (Ed.), Emotions and psychopathology (pp. 229 –257). New York: Plenum Press. Pollock, C. & Andrews, G. (1989). Defense styles associated with specific anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 146, 1500–1502. Rosén, A. (1988). State anxiety and abortion. Anxiety Research, 1, 115–125. Rubino, A., Pezzarossa, B. & Grasso, S. (1991). DMT defences in neurotic and somatically ill patients. In M. Olff, G. Godaert & H. Ursin (Eds.), Quantification of human defence mechanisms (pp. 207–221). Berlin: Springer. Schalling, D. (1986). The development of the KSP inventory. In B. af Klinteberg, D. Schalling & D. Magnusson, Individual development and adjustment (pp. 1– 8). Reports from the Department of Psychology, Stockholm university, No. 64. Spielberger, C., Gorsuch, R. & Lushene, R. (1970). The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI): Test manual Form X. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Spinhoven, P., van Gaalen, H. A. E. & Abraham, R. E. (1995). The Defense Style Questionnaire: A psychometric examination. Journal of Personality Disorders, 9, 124 –133. Stoker, P. (1982). An empirical investigation of the predictive validity of the Defence Mechanism Test in the screening of fast-jet pilots for the Royal Air Force. British Journal of Projective Psychology & Personality Study, 27, 7–12. Stoll, F. & Meier-Civelli, U. (1991). An evaluative study of the Defense Mechanism Test. In M. Olff, G. Godaert & H. Ursin (Eds.), Quantification of human defence mechanisms (pp. 81–97). Berlin: Springer. Scand J Psychol 46 (2005) Sundbom, E. & Armelius, B.-Å. (1992). Reactions to DMT as related to psychotic and borderline personality organization. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 33, 178 –188. Sundbom, E., Binzer, M. & Kullgren, G. (1999). Psychological defense strategies according to the Defense Mechanism Test among patients with severe conversion disorder. Psychotherapy Research, 9, 184 –198. Torjussen, T. & Værnes, R. (1991). The use of the Defence Mechanism Test (DMT) in Norway for selection and stress research. In M. Olff, G. Godaert & H. Ursin (Eds.), Quantification of human defence mechanisms (pp. 172–206). Berlin: Springer. Turkat, D. (1978). Self-esteem research: The role of defensiveness. Psychological Record, 28, 129 –135. Værnes, R. (1982). The DMT predicts inadequate performance under stress. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 23, 37–43. Vaillant, G. E. (1971). Theoretical hierarchy of adaptive ego mechanisms: A 30 year follow-up of 30 men selected for psychological health. Archives of General Psychiatry, 24, 107–118. Vaillant, G. E., Bond, M. & Vaillant, C. O. (1986). An empirically validated hierarchy of defense mechanisms. Archives of General Psychiatry, 43, 786 –794. Vickers, R. R. & Hervig, L. K. (1981). Comparison of three psychological defense mechanism questionnaires. Journal of Personality Assessment, 45, 630 – 680. Zuber, I. & Ekehammar, B. (1997). An empirical look at the Defence Mechanism Test (DMT): Stimulus effects. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 38, 85 –94. Received 18 June 2003, accepted 10 February 2004 © 2005 The Scandinavian Psychological Associations/Blackwell Publishing Ltd.