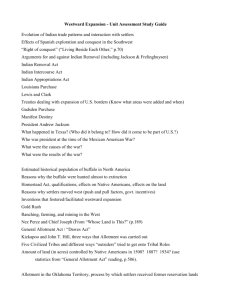

Retelling Allotment: Indian Property Rights and the Myth of Common

advertisement