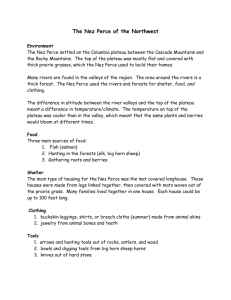

The Allotment Plot: Alice C. Fletcher, E. Jane Gay, and Nez Perce

advertisement