A systematic review of research relating to the Mental Health Act

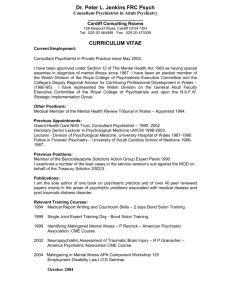

advertisement