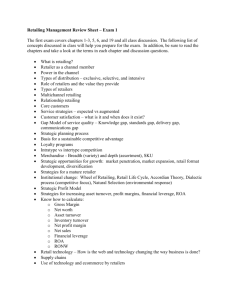

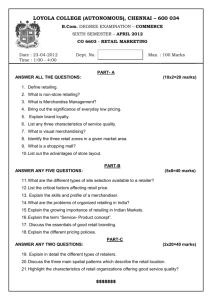

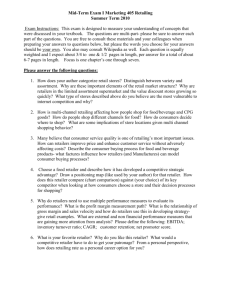

Leveraging Locational Insights within Retail Store Development

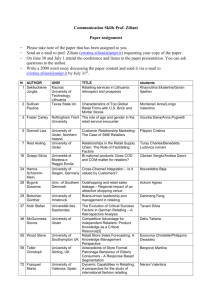

advertisement