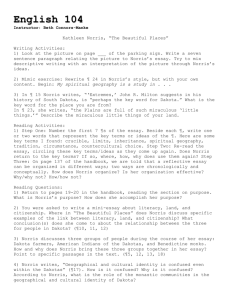

Brief for the United States : U.S. v. Ian P. Norris

advertisement