AP U.S. HISTORY (APUSH) SUMMER ASSIGNMENT 2015 Mrs. Bennett (cbennett@goldercollegeprep.org Welcome to APUSH! I would like to congratulate you on your academic achievements thus far and thank you for accepting the challenge that this course offers. This is a demanding but rewarding course which will require that you do some preparation before you arrive in the fall. You will be taking the AP Exam in May of 2016. Because this course is designed to be equivalent to a college level survey course, it is impossible to cover everything necessary during one school year. Therefore, you will get started on the work by reading a selection of texts to introduce you to the course. The summer assignment has two parts and is due on the first day of class. Be prepared to not only discuss the reading on the first day of class and hand in all assignments, but use this as a foundation for discussions for the entire year. Please email me with any questions about the assignment and if you are stuck, I am available for Office Hours by appointment in August before school begins. REAL Advice from the Class of 2015: “Don’t

“M a ke sure y o u

d o the summer

“Actually read – don’t just highlight – because you’re going to use the information the entire year.” procr astinate!

a ssig nment! It kills

!”

y o ur g ra d e if y o u

– #1 piece of advice from too d o n’t.” many juniors to name “ D on’t

un de r e sti m at

“Memorize the e the sum m er

dates and assi gnm e n t –

presidents!” it ta ke s

“Go to summ er

tim e .” office hours!” – “Don’t trust the printers at school – print it ahead of the first day of school!” Summer Assignment Background: History is inherently biased. Different textbooks and teachers teach history differently. We are going to explore the different histories in APUSH this upcoming year and I want you to be able to develop your own opinion on which history you think is correct. You will be reading three different historians’ opinions on Christopher Columbus. Supplies needed: € Summer homework and reading packet € Brand new college-­‐ruled, sturdy spiral notebook for APUSH (for notes) € Dictionary € Access to a Computer (for essay) Note: If you do not have a computer at home, you should either plan on coming to office hours or going to the Chicago Public Library to type your essays. Part I: Read and Take Notes o Read the attached excerpts: 1. “Introduction” from Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong by James W. Loewen (6 pages) 2. “A Different Mirror: The Making of Multicultural America” from A Different Mirror: History of Multicultural America by Ronald Takaki (9 pages) 3. “Introduction”” from A Patriot’s History of the United States by Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen (8 pages) 4. “Whose History” article by Colleen Flaherty (5 pages) o As you read, take Cornell Notes over each text in the notebook that you plan to use for APUSH next year. I will check for this notebook on the first day of school with your notes in it. o In addition, as you read: o Underline or highlight details you find important or interesting. o Write questions and make notes in the margins about things you do not understand. o Circle words that you do not know and look up their definitions à You will want to have a dictionary handy to complete the reading successfully. o Hint: Be prepared to use your notes for discussion! Make sure you can identify the bias of the authors! Part 2: Essay o Write an analytical essay answering the following prompt: How and why is history retold differently? Which history of America is correct? o You should use evidence from the texts to support your answer. Make sure to cite! o Your response should follow the five paragraphs essay format. o Your response must be typed, double-­‐spaced, size 12, Times New Roman font. o You should BOTH print a copy for the first day of school AND bring a digital copy (email, Google Drive, Flash Drive) to turn in online on the first day of school. o This is your first No Opt Out assignment of Junior Year. Most essays and projects for your junior year classes are considered “No Opt Out” because in college if you do not turn in a major assignment, you will most likely fail. You do not want to start junior year failing AP U.S. History. Part 3: Important Dates and Presidents o Create flashcards and memorize each of the important dates an American presidents o You will be tested on this information on the FIRST DAY of class. Imagine this: It’s July and you’re sitting at home with nothing to do. You complain to your family, “I’m so bored!” Well, history scholars, this will not happen to you because here is a list of awesome activities that you can do when you are bored this summer. Bonus: All of these activities will help you better prepare for U.S. History! Top Five Activities for this Summer:

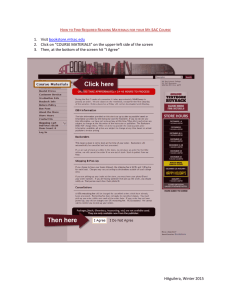

1. Read. •

•

•

Try to read several books over the course of your summer! If you don’t read this summer, your SRI score will go down and that growth that you’ve had in Ms. Daley’s class will be gone! (not reading this summer = not prepared for junior year in the fall) Read fiction, if that is your choice, but try picking up a historical book as well. To prepare for U.S. History next year, check out and read parts of Lies My Teacher Told Me, A People’s History of the United States, or A Patriot’s History of the United States from the library. We’ll be using these in class all next year! 2. Learn your geography. •

•

•

Do you know all 50 states? Learn them… you will have to know them in the fall… Can you find the major mountain ranges of the U.S. on a map? What about rivers, oceans and lakes? Memorize them! The more you know about our geography the farther ahead you will be. 3. Explore your family history. •

•

Stuck for a conversation starter at dinner? Ask your parent or guardian what it was like when they were growing up. Or, ask a grandparent or elderly friend about the Vietnam Era, or World War II. You’ll be surprised how interesting people’s lives really are. 4. Watch history movies! •

•

•

Do you really need to watch 21 Jump Street again? Of course not! If you have a free evening and would like to watch a movie, try something historical. Check out the list of movies on the back of this page for some of my favorite “Awesome Movies that are based on American History!” 5. Wander Chicago! (*see extra credit assignment) •

•

•

•

We are lucky enough to live in the best city in the country. There is history all around us to see and get to by public transit! J Think: gangsters, Prohibition scandals, riots, fire, the world’s first Ferris Wheel, murder, American leaders, slaughter houses, baseball, and so much more! Go to your local library to get FREE passes to visit the many museums to learn more or check out this website for ideas on where to explore: http://www.explorechicago.org. The Chicago History Museum, Field Museum (Native American exhibit), Museum of Science and Industry (U-­‐boat exhibit), or the Frank Lloyd Wright House are some of my favorites! Presidents of the United States—

Memorize the names and dates. I suggest you make note cards for each!

1. George Washington (1789-1797) – None Party then Federalist

2. John Adams (1797-1801) – Federalist

3. Thomas Jefferson (1801-1809) – Democratic-Republican

4. James Madison (1809-1817) – Democratic-Republican

5. James Monroe (1817-1825) – Democratic-Republican

6. John Quincy Adams (1825-1829) – Democratic-Republican

7. Andrew Jackson (1829-1837) – Democrat

8. Martin Van Buren (1837-1841) – Democrat

9. William Harrison (1841) - Whig

10. John Tyler (1841-1845) - Whig

11. James Polk (1845-1849) – Democrat

12. Zachery Tyler (1849-1850) – Whig

13. Millard Fillmore (1850-1853) - Whig

14. Franklin Pierce (1853-1857) - Democrat

15. James Buchanan (1857-1861) – Democrat

16. Abraham Lincoln (1861-1865) – Republican

17. Andrew Johnson (1865-1869) – National

18. Union Ulysses S. Grant (1869-1877) – Republican

19. Rutherford Hayes (1877-1881) – Republican

20. James Garfield (1881) – Republican

21. Chester Arthur (1881-1885) – Republican

22. Grover Cleveland (1885-1889) – Democrat

23. Benjamin Harrison (1889-1893) – Republican

24. Grover Cleveland (1893 – 1897) – Democrat

25. William McKinley (1897-1901) – Republican

26. Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909) – Republican

27. William Taft (1909-1913) – Republican

28. Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921) – Democrat

29. Warren Harding (1921-1923) – Republican

30. Calvin Coolidge (1923-1929) – Republican

31. Herbert Hoover (1929-1933) – Republican

32. Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1933-1945) – Democrat

33. Harry Truman (1945-1953) – Democrat

34. Dwight Eisenhower (1953-1961) – Republican

35. John Fitzgerald Kennedy (1961-1963) – Democrat

36. Lyndon Baines Johnson (1963-1969) – Democrat

37. Richard Nixon (1969-1974) – Republican

38. Gerald Ford (1974-1977) – Republican

39. James Carter (1977-1981) – Democrat

40. Ronald Reagan (1981-1989) – Republican

41. George Bush (1989-1993) – Republican

42. William Clinton (1993-2001) – Democrat

43. George Bush Jr. (2001-2009) – Republican

44. Barack Obama (2009 - ) -- Democrat

Important Dates Memorize the following dates and their events. Again, I suggest making flashcards.

1. 1609 – Jamestown

2. 1676 – Bacon’s Rebellion

3. 1754 – Start of French & Indian War

4. 1763 – Proclamation of 1763

5. 1765 – Stamp Act

6. 1774 – The Coercive Acts

7. 1776 – “Common Sense”, Declaration of Independence

8. 1775 – 1783 Revolutionary War

9. 1777 – Battle of Saratoga

10. 1783 – Treaty of Paris

11. 1786 – Shay’s Rebellion

12. 1787 – Constitutional Convention

13. 1791 – Ratification of the Constitution, First President, Bill of Rights

14. 1800 – Jefferson elected President

15. 1803 – Louisiana Purchase, Marbury v. Madison

16. 1812 – War of 1812

17. 1816 – Clay’s “American System”

18. 1820 – Missouri Compromise

19. 1823 – Monroe Doctrine

20. 1825 – Completion of the Erie Canal

21. 1828 – The Tariff of Abominations, Nullification Crisis

22. 1831 – Worcester v. Georgia

23. 1844 – “54-40 or fight”, Manifest Destiny

24. 1848 – Mexican-American War, Seneca Falls Convention

25. 1850 – Compromise of 1850, Fugitive Slave Act

26. 1854 – Kansas-Nebraska Act

27. 1857 – Dred Scott Case

28. 1858 – Lincoln-Douglas Debates

29. 1860 – Lincoln elected President

Awesome Movies that are based on American History! For those lazy summer days when you just don’t want to leave the couch… Get some popcorn and enjoy these classics! Movie Title Historical Topic The Crucible Salem Witch Trials The Last of the Mohicans The French and Indian War 1776 The Second Constitutional Convention The Patriot The American Revolution Far and Away Irish Immigration/Homesteading Amistad Slavery Little Women Antebellum North/women’s roles Gangs of New York Immigrants vs. Nativists in NYC/Draft Riots The Alamo The Mexican-­‐American War Glory The Civil War – African American regiments Lincoln The Civil War – The 13th Amendment Gettysburg The Civil War – Gettysburg Gone with the Wind The Civil War/Reconstruction – Southern perspective Dances with Wolves The American Frontier – Native Americans struggles Tombstone The American Frontier – Cowboys Unforgiven The American Frontier – Cowboys The Color Purple African Americans in the early 1900s Titanic Early 20th century immigration/technology Flyboys WWI fighter pilots Iron Jawed Angels Women’s suffrage The Godfather Organized crime/gangsters The Untouchables Organized crime/gangsters (Chicago!) Public Enemy Organized crime/gangsters (Chicago!) The Great Gatsby The Roaring Twenties Modern Times The Great Depression The Grapes of Wrath The Great Depression The Great Debaters Jim Crow South Memphis Belle WWII combat (planes) Saving Private Ryan WWII combat (D-­‐Day) Pearl Harbor WWII combat U-­‐571 WWII combat (submarine) Hiroshima Hiroshima Atomic Café Post-­‐WWII paranoia October Sky Space Exploration (teenage triumph) Apollo 13 Space Exploration Dr. Strangelove The Cold War/nuclear arms race Thirteen Days The Cuban Missile Crisis Malcolm X Civil Rights Mississippi Burning Civil Rights/racism Rudy 1960s and football Apocalypse Now The Vietnam War Platoon The Vietnam War Nixon Nixon/Watergate Black Hawk Down Battle of Mogadishu (US vs Somalia) Fahrenheit 9/11 9/11 The Hurt Locker War in Iraq Note: Many of the films above are rated R. Please check with your parents before viewing. Introduction to Lies My Teacher Told Me

By James W. Loewen

http://www.uvm.edu/~jloewen/content.php?file=liesmyteachertoldmeintroduction.html

"It would be better not to know so many things than to know so many things that are not

so." -- Felix Okoye

"Those who don't remember the past are condemned to repeat the eleventh grade." -James Loewen

"American history is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than

anything anyone has ever said about it." -- James Baldwin

"Concealment of the historical truth is a crime against the people." -- General Petro

G.Grigorenko, samizdat letter to history journal, c. 1975, U.S.S.R.

High school students hate history. When they list their favorite subjects, history always

comes in last. They consider it "the most irrelevant" of 21 school subjects, not applicable

to life today. "Borr-r-ring" is the adjective they apply to it. When they can, they avoid it,

even though most students get higher grades in history than in math, science, or English.

Even when they are forced to take history, they repress it, so every year or two another

study decries what our 17-year-olds don't know.

African American, Native American, and Latino students view history with a special

dislike. They also learn it especially poorly. Students of color do only slightly worse than

white students in mathematics. Pardoning my grammar, they do more worse in English

and most worse in history. Something intriguing is going on here: surely history is not

more difficult than trigonometry or Faulkner. I will argue later that high school history so

alienates people of color that doing badly may be a sign of mental health! Students don't

know they're alienated, only that they "don't like social studies" or "aren't any good at

history." In college, most students of color give history departments a wide berth.

Many history teachers perceive the low morale in their classrooms. If they have lots of

time, light family responsibilities, some resources, and a flexible principal, some teachers

respond by abandoning the overstuffed textbooks and reinventing their American history

courses. All too many teachers grow disheartened and settle for less. At least dimly aware

that their students are not requiting their own love of history, they withdraw some of their

energy from their courses. Gradually they settle for just staying ahead of their students in

the books, teaching what will be on the test, and going through the motions.

College teachers in most disciplines are happy when their students have had more rather

than less exposure to the subject before they reach college. Not in history. History

professors in college routinely put down high school history courses. A colleague of mine

calls his survey of American history "Iconoclasm I and II," because he sees his job as

disabusing his charges of what they learned in high school. In no other field does this

happen. Mathematics professors, for instance, know that non-Euclidean geometry is

rarely taught in high school, but they don't assume that Euclidean geometry was

mistaught. English literature courses don't presume that "Romeo and Juliet" was

misunderstood in high school. Indeed, a later chapter will show that history is the only

field in which the more courses students take, the stupider they become.

Perhaps I do not need to convince you that American history is important. More than any

other topic, it is about us. Whether one deems our present society wondrous or awful or

both, history reveals how we got to this point. Understanding our past is central to our

ability to understand ourselves and the world around us. We need to know our history,

and according to C. Wright Mills, we know we do. Outside of school, Americans do

show great interest in history. Historical novels often become bestsellers, whether by

Gore Vidal (Lincoln, Burr) or Dana Fuller Ross (Idaho! Utah! Nebraska! Oregon!

Missouri! and on! and on!). The National Museum of American History is one of the

three big draws of the Smithsonian Institution. The Civil War series attracted new

audiences to public television. Movies tied to history have fascinated us from Birth of a

Nation through Gone With the Wind to Dances With Wolves and JFK.

Our situation is this: American history is full of fantastic and important stories. These

stories have the power to spellbind audiences, even audiences of difficult seventh graders.

These same stories show what America has been about and have direct relevance to our

present society. American audiences, even young ones, need and want to know about

their national past. Yet they sleep through the classes that present it.

What has gone wrong?

We begin to get a handle on that question by noting that textbooks dominate history

teaching more than any other field. Students are right: the books are boring. The stories

they tell are predictable because every problem is getting solved, if it has not been

already. Textbooks exclude conflict or real suspense. They leave out anything that might

reflect badly upon our national character. When they try for drama, they achieve only

melodrama, because readers know that everything will turn out wonderful in the end.

"Despite setbacks, the United States overcame these challenges," in the words of one of

them. Most authors don't even try for melodrama. Instead, they write in a tone that if

heard aloud might be described as "mumbling lecturer." No wonder students lose interest.

Textbooks almost never use the present to illuminate the past. They might ask students to

learn about gender roles in the present, to prompt thinking about what women did and did

not achieve in the suffrage movement or the more recent women's movement. They

might ask students to do family budgets for a janitor and a stock broker, to prompt

thinking about labor unions and social class in the past or present. They might, but they

don't. The present is not a source of information for them. No wonder students find

history "irrelevant" to their present lives.

Conversely, textbooks make no real use of the past to illuminate the present. The present

seems not to be problematic to them. They portray history as a simple-minded morality

play. "Be a good citizen" is the message they extract from the past for the present. "You

have a proud heritage. Be all that you can be. After all, look at what the United States has

done." While there is nothing wrong with optimism, it does become something of a

burden for students of color, children of working class parents, girls who notice an

absence of women who made history, or any group that has not already been

outstandingly successful. The optimistic textbook approach denies any understanding of

failure other than blaming the victim. No wonder children of color are alienated. Even for

male children of affluent white families, bland optimism gets pretty boring after eight

hundred pages.

These textbooks in American history stand in sharp contrast to the rest of our schooling.

Why are they so bad? Nationalism is one of the culprits. Their contents are muddled by

the conflicting desires to promote inquiry and indoctrinate blind patriotism. "Take a look

in your history book, and you'll see why we should be proud," goes an anthem often sung

by high school glee clubs, but we need not even take a look inside. The difference begins

with their titles: The Great Republic, The American Way, Land of Promise, Rise of the

American Nation. Such titles differ from all other textbooks students read in high school

or college. Chemistry books are called Chemistry or Principles of Chemistry, not Rise of

the Molecule. Even literature collections are likely to be titled Readings in American

Literature. Not most history books. And you can tell these books from their covers,

graced with American flags, eagles, and the Statue of Liberty.

Inside their glossy covers, American history books are full of information - overly full.

These books are huge. My collection of a dozen of the most popular averages four and a

half pounds in weight and 888 pages in length. No publisher wants to be shut out from an

adoption because their book left out a detail of concern to an area or a group. Authors

seem compelled to include a paragraph about every president, even Chester A. Arthur

and Millard Fillmore. Then there are the review pages at the end of each chapter. Land of

Promise, to take one example, enumerates 444 "Main Ideas" at the ends of its chapters. In

addition, it lists literally thousands of "Skill Activities," "Key Terms," "Matching" items,

"Fill in the Blanks," "Thinking Critically" questions, and "Review Identifications" as well

as still more "Main Ideas" at the ends of each section within its chapters. At year's end,

no student can remember 444 main ideas, not to mention 624 key terms and countless

other "factoids," so students and teachers fall back on one main idea: to memorize the

terms for the test following each chapter, then forget them to clear the synapses for the

next chapter. No wonder high school graduates are notorious for forgetting in which

century the Civil War was fought!

None of the facts is memorable, because they are presented as one damn thing after

another. While they include most of the trees and all too many twigs, authors forget to

give readers even a glimpse of what they might find memorable: the forests. Textbooks

stifle meaning as they suppress causation. Therefore students exit them without

developing the ability to think coherently about social life.

Even though the books are fat with detail, even though the courses are so busy they rarely

reach 1960, our teachers and our textbooks still leave out what we need to know about

the American past. Often the factoids are flatly wrong or unknowable. In sum, startling

errors of omission and distortion mar American histories. This book is about how we are

mistaught.

Errors in history textbooks do not often get corrected, partly because the history

profession does not bother to review them. Occasionally outsiders do: Frances

FitzGerald's 1979 study, America Revised, was a bestseller, but she made no impact on

the industry. In a sarcastic passage her book pointed out how textbooks ignored or

distorted the Spanish impact on Latin America and the colonial United States. "Text

publishers may now be on the verge of rewriting history," she predicted, but she was

wrong - the books have not changed.

History can be imagined as a pyramid. At its base are the millions of primary sources the plantation records, city directories, speeches, songs, photographs, newspaper articles,

diaries, and letters from the time. Based on these primary materials, historians write

secondary works - books and articles on subjects ranging from deafness on Martha's

Vineyard to Grant's tactics at Vicksburg. Historians produce hundreds of these works

every year, many of them splendid. In theory, a few historians working individually or in

teams then synthesize the secondary literature into tertiary works - textbooks covering all

phases of United States history.

In practice, however, it doesn't work that way. Instead, history textbooks are clones of

each other. The first thing editors do when recruiting new authors is to send them half a

dozen examples of the competition. Often a textbook is not written by the authors whose

names grace its cover, but by minions deep in the bowels of the publisher's offices. When

historians do write them, they face snickers from their colleagues and deans - tinged with

envy, but snickers nonetheless: "Why are you writing pedagogy instead of doing

scholarship?"

The result is not happy for textbook scholarship. Many history textbooks do list up-tothe-minute secondary sources in bibliographies at the ends of chapters, but the contents of

the chapters remain totally traditional - unaffected by the new research.

What would we think of a course in poetry in which students never read a poem? The

editors' voice in literature textbooks may be no more interesting than in history, but at

least that voice stills when the textbook presents original materials of literature. The

universal processed voice of history textbook authors insulates students from the raw

materials of history. Rarely do authors quote the speeches, songs, diaries, and letters that

make the past come alive. Students do not need to be protected from this material. They

can just as well read one paragraph from William Jennings Bryan's "Cross of Gold"

speech as read two paragraphs about it, which is what American Adventures substitutes.

No wonder students find the textbooks dull.

Textbooks also keep students in the dark about the nature of history. History is furious

debate informed by evidence and reason, not just answers to be learned. Textbooks

encourage students to believe that history is learning facts. "We have not avoided

controversial issues" announces one set of textbook authors; "instead, we have tried to

offer reasoned judgments" on them - thus removing the controversy! No wonder their text

turns students off! Because textbooks employ this god-like voice, it never occurs to most

students to question them. "In retrospect I ask myself, why didn't I think to ask for

example who were the original inhabitants of the Americas, what was their life like, and

how did it change when Columbus arrived," wrote a student of mine. "However, back

then everything was presented as if it were the full picture," she continued, "so I never

thought to doubt that it was." Tests supplied by the textbook publishers then tickle

students' throats with multiple choice items to get them to regurgitate the factoids they

"learned." No wonder students don't learn to think critically.

As a result of all this, high school graduates are hamstrung in their efforts to apply logic

and information to controversial issues in our society. (I know because I encounter them

the next year as college freshmen.) We've got to do better. Five sixths of all Americans

never take a course in American history beyond high school. What our citizens "learn"

there forms most of what they know of our past.

America's history merits remembering and understanding. This book includes ten

chapters of amazing stories - some wonderful, some ghastly - in American history.

Arranged in roughly chronological order, these chapters do not relate mere details but

events and processes that had and have important consequences. Yet most textbooks

leave out or distort them. I know because for several years I have been lugging around

twelve textbooks, taking them seriously as works of history and ideology, studying what

they say and don't say, and trying to figure out why. I chose the twelve to represent the

range of books available for American history courses. Two, Discovering American

History and The American Adventure, are "inquiry" textbooks, composed of maps,

illustrations, and extracts from primary sources like diaries and laws, linked by narrative

passages. These books are supposed to invite students to "do" history themselves. The

American Way, Land of Promise, The United States -- A History of the Republic,

American History, The American Tradition, are traditional high school narrative history

textbooks. Three textbooks, American Adventures, Life and Liberty, and Challenge of

Freedom, are intended for junior high students but are often used by "slow" senior high

classes. Triumph of the American Nation and The American Pageant are also used on

college campuses. These twelve have been my window into the world of what high

school students carry home, read, memorize, and forget. In addition, I have spent many

hours observing high school history classrooms in Mississippi, Vermont, and the

Washington metropolitan area.

The eleventh chapter analyzes the process of textbook creation and adoption to explain

what causes textbooks to be as bad as they are. I must confess an interest here: I once

wrote a history textbook. Written with co-authors, Mississippi: Conflict and Change was

the first revisionist state history textbook in America. Although Conflict and Change won

the Lillian Smith Award for "best nonfiction about the South" in 1975, Mississippi

rejected it for public school use, so the authors and three school systems sued the

textbook board. In April, 1980, Loewen et al. v. Turnipseed et al. resulted in a sweeping

victory based on the first and fourteenth amendments. The experience taught me firsthand more than most authors or publishers ever want to know about the textbook

adoption process. I have also learned that not all the blame can be laid at the doorstep of

the adoption agencies. Chapter twelve looks at the effects of using these textbooks. It

shows that they actually make students stupid. An epilogue, "The Future Lies Ahead,"

suggests distortions and omissions that went undiscussed in earlier chapters and

recommends ways that teachers can teach and students can learn American history more

honestly - sort of an inoculation program against the next lies we are otherwise sure to

encounter.

6/8/2015

Oklahoma legislature targets AP US history framework for being 'negative'

(https://www.insidehighered.com)

Oklahoma legislature targets AP US history framework for

being 'negative'

Submitted by Colleen Flaherty on February 23, 2015 - 3:00am

American history is constantly debated not only by historians but by politicians. So it was largely

unsurprising when some Republicans started to criticize the new Advanced Placement U.S. history

framework last year for allegedly downplaying positive elements of America’s past. Many historians

were caught off guard last week, however, when the criticism grew legs, at least in Oklahoma: a

legislative committee there easily passed a bill [1] declaring the new AP curriculum an “emergency”

threatening the “public peace, health and safety,” to be defunded in the coming school year.

Facing a wave of criticism, the bill’s sponsor, Rep. Daniel Fisher, said late last week that he was

reworking the bill the make it less “ambiguous,” and that he was in fact “very supportive of the AP

program" in general. (The current version of his bill states that funding will not be revoked if the state

reverts back to the prior framework and exam.) Another legislator said the rewritten bill will ask

Oklahoma’s Board of Education to review the new curriculum, instead of cutting funding, The

Oklahoman [2] reported.

Although the debate has gone farthest in Oklahoma, policy makers in Georgia [3], Texas [4], South

Carolina [5], North Carolina [6] and Colorado [7] also have expressed opposition to the new curriculum,

according to The Washington Post.

The Oklahoma bill’s future is unclear, and some aren’t taking it too seriously. It served as comedic

fodder for the Web site Funny or Die [8], for example, which published a parody of a new AP history

exam featuring questions such as: "Women only began voting in the year 1920 because: a.) they

just didn’t want to before then, it was weird; b.) a woman’s tiny hands couldn’t lift the heavy paper

ballots of the time; c.) they were all too busy sewing flags; d.) all of the above."

But the movement has historians concerned about the possible spread of legislative actions against

the AP framework -- and the fate of what they say is a good test that encourages precisely the kind

of historical thinking they want students to pick up on their way to college.

The History Debate on 'This Week'

The debate on AP history will be discussed Friday on "This Week," [9] Inside Higher Ed's free news

podcast. Sign up here [10] to be notified of new "This Week" podcasts.

“The big problem overall is this issue of people’s willingness to let teachers explore the complexities

of history, to recognize that what you want students to learn is historical thinking, and to see the

https://www.insidehighered.com/print/news/2015/02/23/oklahoma-legislature-targets-ap-us-history-framework-being-negative?width=775&height=500&iframe=true

1/5

6/8/2015

Oklahoma legislature targets AP US history framework for being 'negative'

complexity that makes history more than a simple story,” said James Grossman, executive director

of the American Historical Association. “That’s what revisionism is. It’s the only way the discipline

changes over time, as it takes up new things and has new insights. And one of the ways that gets

translated into high school classrooms is through the AP.”

David Wrobel, Merrick Chair of Western History at the University of Oklahoma, said there’s

“universal” opposition to the bill among his colleagues and the many high school history teachers he

works with through institutes and grants to promote “K-20” education within his state. Wrobel said he

shared some of Grossman’s concerns, as well as practical ones about how high schools will

scramble to create a new, college-level U.S. history program by fall if the bill is ultimately successful,

and how it will adversely affect Oklahoma students competing for admission to college.

“You take a nationally recognized measure of excellence and student achievement away from

students that are applying to colleges and universities across the country,” Wrobel said, “and

students from the state of Oklahoma are obviously disadvantaged against those coming from

institutions where they have had an opportunity to do AP U.S. history.”

Students also miss out on a course they think is valuable, he said, since AP U.S. history students in

formal course evaluations “talk about what the course has meant to them, and the vast majority not

only mention how it made them critical thinkers and enhanced their content knowledge, but how AP

U.S. history also enhanced their understanding of what citizenship means.”

Criticism of the new curriculum [11], known as APUSH, and its publisher, the College Board, got

going last year, with some conservatives saying that the test ignored important aspects of American

history and cast it in too negative a light. In August, the Republican National Committee approved a

resolution [12] summarizing their concerns and asking state legislators to investigate the test and for

Congress to “withhold any federal funding to the College Board (a private nongovernmental

organization) until the APUSH course and examination have been rewritten in a transparent manner

to accurately reflect U.S. history without a political bias and to respect the sovereignty of state

standards, and until sample examinations are made available to educators, state and local

officials[.]”

Among the Republican committee’s more specific concerns were that the framework “includes little

or no discussion of the Founding Fathers, the principles of the Declaration of Independence, the

religious influences on our nation’s history and many other critical topics that have always been part

of the APUSH course” and that it “excludes discussion of the U.S. military (no battles, commanders

or heroes) and omits many other individuals and events that greatly shaped our nation’s history (for

example, Albert Einstein, Jonas Salk, George Washington Carver, Rosa Parks, Dr. Martin Luther

King, Tuskegee Airmen, the Holocaust).”

In response to the criticism, the College Board released a practice exam [13] for the new framework,

hoping to reduce suspicions about the test. The questions suggest that, contrary to the Republican

resolution, students will study the founding of the United States and the civil rights movement, but

also will explore topics such as poverty in American life that are less triumphal than battle victories.

In an open letter, David Coleman, College Board president, said he hoped the unprecedented move

of releasing an exam to parties other than certified AP teachers would quell concerns that the

framework neglected or misrepresented key elements of American history.

"People who are worried that AP U.S. history students will not need to study our nation's founders

need only take one look at this exam to see that our founders are resonant throughout," Coleman

said, noting that the framework was just that, and that local teachers could add to it as they saw fit.

But the move did little to alleviate tensions about the new test. Stanley Kurtz wrote in the National

Review [14] later that month that the framework was “closely tied to a movement of left-leaning

historians that aims to ‘internationalize’ the teaching of American history. The goal is to ‘end

https://www.insidehighered.com/print/news/2015/02/23/oklahoma-legislature-targets-ap-us-history-framework-being-negative?width=775&height=500&iframe=true

2/5

6/8/2015

Oklahoma legislature targets AP US history framework for being 'negative'

American history as we have known it’ by substituting a more ‘transnational’ narrative for the

traditional account.” His commentary is light on specific examples of problematic questions or

concepts, but he wrote that the older, relatively short framework allowed "liberals, conservatives and

anyone in between [to] teach U.S. history their way, and still see their students do well on the AP

test." By contrast, he said, the "new and vastly more detailed guidelines can only be interpreted as

an attempt to hijack the teaching of U.S. history on behalf of a leftist political and ideological

perspective. The College Board has drastically eroded the freedom of states, school districts,

teachers and parents to choose the history they teach their children."

In September, the curriculum was a hot topic at the Values Voter Summit in Washington. Ben

Carson, a pediatric neurosurgeon and professor emeritus of medicine at Johns Hopkins University

who has considered running for president, told audience members, “I think most people, when they

finish that course, they’d be ready to sign up for ISIS,” or the so-called Islamic State, The

Washington Post [15] reported.

Grossman, of the American Historical Association, countered some of the talk in his own New York

Times op-ed [16] about the importance of revisionism in historians’ work -- however disquieting.

“Fewer and fewer college professors are teaching the [U.S.] history our grandparents learned -memorizing a litany of names, dates and facts -- and this upsets some people,” Grossman wrote.

“‘College-level work’ now requires attention to context, and change over time; includes greater use

of primary sources; and reassesses traditional narratives. This is work that requires and builds

empathy, an essential aspect of historical thinking.”

He added, “The educators and historians who worked on the new history framework were right to

emphasize historical thinking as an essential aspect of civic culture. Their efforts deserve a spirited

debate, one that is always open to revision, rather than ill-informed assumptions or political

partisanship.”

The AP U.S. history exam always has emphasized critical thinking, differentiating it from some of the

more rote curriculums mandated by some states. But whereas the old framework focused on the

colonial period to about the 1980s, the new framework places a bigger emphasis on historical

thinking and on the Americas from the 1490s to the 1600s and the U.S. after the Cold War, including

9/11 and the wars that followed.

In a statement addressing the Oklahoma controversy, the College Board said the framework and

other AP materials were written by seasoned educators who sought to take “a more transparent and

flexible approach, offering guidance to teachers on what might be in the exam while providing for

alignment with local requirements and standards.” The statement also noted that Oklahoma students

are on track to earn nearly $1 million in college credit this year through the exam -- another

argument many opponents of the bill have raised. Grossman said it was his opinion that the new test reflected the advancement of historical study and

a greater emphasis on historical thinking -- a good thing -- but that it wasn’t radically or ideologically

different from the last. He pointed to a sample essay question, for example, that presents two very

different views of Manifest Destiny, the philosophy of westward expansion, and asks students to

compare them. The test doesn’t suggest that one is better or more accurate than the other, however,

he said.

https://www.insidehighered.com/print/news/2015/02/23/oklahoma-legislature-targets-ap-us-history-framework-being-negative?width=775&height=500&iframe=true

3/5

6/8/2015

Oklahoma legislature targets AP US history framework for being 'negative'

Ben Keppel, an associate professor of American history at the University of Oklahoma, said he

thought the bill “was a really horrible idea and a misunderstanding of what history is and what history

teachers do.”

The new framework, he said, “is a modern curriculum” that asks students to think critically about

different pieces of evidence and different perspectives. Without such richness of texts, he said,

“that’s not intellectual history, that’s not education, that’s a kind of ideological indoctrination.” Like

Wrobel, he guessed that his department, if polled, would demonstrate a “rare” show of unanimity of

opinion against the legislation.

It’s unclear from Fisher’s bill exactly what constitutes an emergent threat to the public in the new

framework. He did not return a request for comment. But Wrobel said many of his public statements

and those of other critics touched on the concept of American exceptionalism.

Wrobel, who has written several books on the topic, said he disagreed strongly with the way the

term was being used as a kind of “political football” or “litmus test” for one’s political affiliation. The

actual concept of American exceptionalism, which has been the subject of rich scholarship for

centuries, really means that the U.S. “has faced a whole series of incredibly complicated challenges

and nonetheless managed to develop into a largely functional, multicultural democracy,” he said.

Wrobel added that it was unfair that AP U.S. history was being “saddled” with an “unsubtle” debate,

and that he “would love for people not to be drawn into sound bites or easy assumptions about a

curriculum, but to get to talk with students and teachers about what incredibly thoughtful, smart

students we are seeing develop from programs that push them intellectually.”

The College Board’s statement also addressed the American exceptionalism debate, which it said

has been “marred by misinformation.”

“The redesigned AP U.S. History course framework includes many inspiring examples of American

exceptionalism,” the board said. “Rather than reducing the role of the founders, the new framework

places more focus on their writings and their essential role in our nation's history, and recognizes

American heroism, courage and innovation.”

https://www.insidehighered.com/print/news/2015/02/23/oklahoma-legislature-targets-ap-us-history-framework-being-negative?width=775&height=500&iframe=true

4/5

6/8/2015

Oklahoma legislature targets AP US history framework for being 'negative'

It continues: “Because this is a college-level course, students must also examine how Americans

have addressed challenging situations like slavery. Neither the AP program, nor the thousands of

American colleges and universities that award credit for AP U.S. history exams, will allow the

censorship of such topics, which can and should be taught in a way that inspires students with

confidence in America’s commitment to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

Grossman said he didn’t think the debate was going away any time soon, given the

unique “accessibility” of history.

“History has an unusual combination of being politically sensitive and also a discipline that more

people feel they know more about than some other disciplines,” he said, noting it would be “hard to

imagine” a state legislature mandating what a chemistry teacher should be teaching, for example.

“Historians have been successful writing for the general public and many people have a deep and

abiding interest in history, and that’s a wonderful thing. But there are going to be more legislators

who feel they are qualified in this area.”

Teaching and Learning [17]

Source URL: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/02/23/oklahoma-legislature-targets-ap-us-history-frameworkbeing-negative?width=775&height=500&iframe=true

Links:

[1] http://webserver1.lsb.state.ok.us/cf_pdf/2015-16%20INT/hB/HB1380%20INT.PDF

[2] http://newsok.com/oklahoma-lawmaker-reworking-advanced-placement-bill-says-he-supports-approgram/article/5394536

[3] http://atlanta.cbslocal.com/2015/02/18/georgia-state-senator-ap-u-s-history-test-should-be-scrapped/

[4] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/09/18/texas-ap-history_n_5842874.html

[5] http://www.thestate.com/2014/09/19/3692800_sc-common-core-opponents-target.html?rh=1

[6] http://www.newsobserver.com/2014/11/26/4356766_nc-board-of-education-to-hear.html?rh=1

[7] http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2014/10/05/fa6136a2-4b12-11e4-b72e-d60a9229cc10_story.html

[8] http://www.funnyordie.com/articles/ea5dc8d02c/the-new-more-patriotic-ap-history-test

[9] https://www.insidehighered.com/audio/week

[10] https://www.insidehighered.com/this-week-sign-up

[11] http://media.collegeboard.com/digitalServices/pdf/ap/ap-us-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

[12] http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/curriculum/RNC.JPG

[13] http://media.collegeboard.com/digitalServices/pdf/ap/ap-us-history-practice-exam.pdf

[14] http://www.nationalreview.com/corner/386202/how-college-board-politicized-us-history-stanley-kurtz

[15] http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/wp/2014/09/29/ben-carson-new-ap-u-s-history-course-will-makekids-want-to-sign-up-for-isis/

[16] http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/02/opinion/the-new-history-wars.html?_r=0

[17] https://www.insidehighered.com/news/focus/teaching-and-learning

undefined

undefined

https://www.insidehighered.com/print/news/2015/02/23/oklahoma-legislature-targets-ap-us-history-framework-being-negative?width=775&height=500&iframe=true

5/5

A Patriot’s History of the United States

A Patriot’s History of the United States

FROM COLUMBUS’S GREAT DISCOVERY TO THE WAR ON TERROR

Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen

SENTINEL

SENTINEL

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), Cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South

Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2004 by Sentinel, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright © Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen, 2004

All rights reserved

CIP DATA AVAILABLE.

ISBN: 1-4295-2229-1

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any

means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written

permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means

without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only

authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of

copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

To Dee and Adam

—Larry Schweikart

For my mom

—Michael Allen

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Larry Schweikart would like to thank Jesse McIntyre and Aaron Sorrentino for their contribution to

charts and graphs; and Julia Cupples, Brian Rogan, Andrew Gough, and Danielle Elam for

research. Cynthia King performed heroic typing work on crash schedules. The University of

Dayton, particularly Dean Paul Morman, supported this work through a number of grants.

Michael Allen would like to thank Bill Richardson, Director of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences

at the University of Washington, Tacoma, for his friendship and collegial support for over a decade.

We would both like to thank Mark Smith, David Beito, Brad Birzer, Robert Loewenberg, Jeff

Hanichen, David Horowitz, Jonathan Bean, Constantine Gutzman, Burton Folsom Jr., Julius Amin,

and Michael Etchison for comments on the manuscript. Ed Knappman and the staff at New

England Publishing Associates believed in this book from the beginning and have our undying

gratitude. Our special thanks to Bernadette Malone, whose efforts made this possible; to Megan

Casey for her sharp eye; and to David Freddoso for his ruthless, but much needed, pen.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER ONE:

The City on the Hill, 1492–1707

CHAPTER TWO:

Colonial Adolescence, 1707–63

CHAPTER THREE:

Colonies No More, 1763–83

CHAPTER FOUR:

A Nation of Law, 1776–89

CHAPTER FIVE:

Small Republic, Big Shoulders, 1789–1815

CHAPTER SIX:

The First Era of Big Central Government, 1815–36

CHAPTER SEVEN:

Red Foxes and Bear Flags, 1836–48

CHAPTER EIGHT:

The House Dividing, 1848–60

CHAPTER NINE:

The Crisis of the Union, 1860–65

CHAPTER TEN:

Ideals and Realities of Reconstruction, 1865–76

CHAPTER ELEVEN:

Lighting Out for the Territories, 1861–90

CHAPTER TWELVE:

Sinews of Democracy, 1876–96

CHAPTER THIRTEEN:

“Building Best, Building Greatly,” 1896–1912

CHAPTER FOURTEEN:

War, Wilson, and Internationalism, 1912–20

CHAPTER FIFTEEN:

The Roaring Twenties and the Great Crash, 1920–32

CHAPTER SIXTEEN:

Enlarging the Public Sector, 1932–40 The New Deal: Immediate Goals, Unintended Results

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN:

Democracy’s Finest Hour, 1941–45

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN:

America’s “Happy Days,” 1946–59

CHAPTER NINETEEN:

The Age of Upheaval, 1960–74

CHAPTER TWENTY:

Retreat and Resurrection, 1974–88

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE:

The Moral Crossroads, 1989–2000

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO:

America, World Leader, 2000 and Beyond

CONCLUSION

NOTES

SELECTED READING

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

Is America’s past a tale of racism, sexism, and bigotry? Is it the story of the conquest and rape of a

continent? Is U.S. history the story of white slave owners who perverted the electoral process for

their own interests? Did America start with Columbus’s killing all the Indians, leap to Jim Crow

laws and Rockefeller crushing the workers, then finally save itself with Franklin Roosevelt’s New

Deal? The answers, of course, are no, no, no, and NO.

One might never know this, however, by looking at almost any mainstream U.S. history textbook.

Having taught American history in one form or another for close to sixty years between us, we are

aware that, unfortunately, many students are berated with tales of the Founders as self-interested

politicians and slaveholders, of the icons of American industry as robber-baron oppressors, and of

every American foreign policy initiative as imperialistic and insensitive. At least Howard Zinn’s A

People’s History of the United States honestly represents its Marxist biases in the title!

What is most amazing and refreshing is that the past usually speaks for itself. The evidence is there

for telling the great story of the American past honestly—with flaws, absolutely; with

shortcomings, most definitely. But we think that an honest evaluation of the history of the United

States must begin and end with the recognition that, compared to any other nation, America’s past

is a bright and shining light. America was, and is, the city on the hill, the fountain of hope, the

beacon of liberty. We utterly reject “My country right or wrong”—what scholar wouldn’t? But in

the last thirty years, academics have taken an equally destructive approach: “My country, always

wrong!” We reject that too.

Instead, we remain convinced that if the story of America’s past is told fairly, the result cannot be

anything but a deepened patriotism, a sense of awe at the obstacles overcome, the passion invested,

the blood and tears spilled, and the nation that was built. An honest review of America’s past would

note, among other observations, that the same Founders who owned slaves instituted numerous

ways—political and intellectual—to ensure that slavery could not survive; that the concern over not

just property rights, but all rights, so infused American life that laws often followed the practices of

the common folk, rather than dictated to them; that even when the United States used her military

power for dubious reasons, the ultimate result was to liberate people and bring a higher standard of

living than before; that time and again America’s leaders have willingly shared power with those

who had none, whether they were citizens of territories, former slaves, or disenfranchised women.

And we could go on.

The reason so many academics miss the real history of America is that they assume that ideas don’t

matter and that there is no such thing as virtue. They could not be more wrong. When John D.

Rockefeller said, “The common man must have kerosene and he must have it cheap,” Rockefeller

was already a wealthy man with no more to gain. When Grover Cleveland vetoed an insignificant

seed corn bill, he knew it would hurt him politically, and that he would only win condemnation

from the press and the people—but the Constitution did not permit it, and he refused.

Consider the scene more than two hundred years ago when President John Adams—just voted out

of office by the hated Republicans of Thomas Jefferson—mounted a carriage and left Washington

even before the inauguration. There was no armed struggle. Not a musket ball was fired, nor a

political opponent hanged. No Federalists marched with guns or knives in the streets. There was no

guillotine. And just four years before that, in 1796, Adams had taken part in an equally momentous

event when he won a razor-thin close election over Jefferson and, because of Senate rules, had to

count his own contested ballots. When he came to the contested Georgia ballot, the great

Massachusetts revolutionary, the “Duke of Braintree,” stopped counting. He sat down for a moment

to allow Jefferson or his associates to make a challenge, and when he did not, Adams finished the

tally, becoming president. Jefferson told confidants that he thought the ballots were indeed in

dispute, but he would not wreck the country over a few pieces of paper. As Adams took the oath of

office, he thought he heard Washington say, “I am fairly out and you are fairly in! See which of us

will be the happiest!”1 So much for protecting his own interests! Washington stepped down freely

and enthusiastically, not at bayonet point. He walked away from power, as nearly each and every

American president has done since.

These giants knew that their actions of character mattered far more to the nation they were creating

than mere temporary political positions. The ideas they fought for together in 1776 and debated in

1787 were paramount. And that is what American history is truly about—ideas. Ideas such as “All

men are created equal”; the United States is the “last, best hope” of earth; and America “is great,

because it is good.”

Honor counted to founding patriots like Adams, Jefferson, Washington, and then later, Lincoln and

Teddy Roosevelt. Character counted. Property was also important; no denying that, because with

property came liberty. But virtue came first. Even J. P. Morgan, the epitome of the so-called robber

baron, insisted that “the first thing is character…before money or anything else. Money cannot buy

it.”

It is not surprising, then, that so many left-wing historians miss the boat (and miss it, and miss it,

and miss it to the point where they need a ferry schedule). They fail to understand what every

colonial settler and every western pioneer understood: character was tied to liberty, and liberty to

property. All three were needed for success, but character was the prerequisite because it put the

law behind property agreements, and it set responsibility right next to liberty. And the surest way to

ensure the presence of good character was to keep God at the center of one’s life, community, and

ultimately, nation. “Separation of church and state” meant freedom to worship, not freedom from

worship. It went back to that link between liberty and responsibility, and no one could be taken

seriously who was not responsible to God. “Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is liberty.” They

believed those words.

As colonies became independent and as the nation grew, these ideas permeated the fabric of the

founding documents. Despite pits of corruption that have pockmarked federal and state politics—

some of them quite deep—and despite abuses of civil rights that were shocking, to say the least, the

concept was deeply imbedded that only a virtuous nation could achieve the lofty goals set by the

Founders. Over the long haul, the Republic required virtuous leaders to prosper.

Yet virtue and character alone were not enough. It took competence, skill, and talent to build a

nation. That’s where property came in: with secure property rights, people from all over the globe

flocked to America’s shores. With secure property rights, anyone could become successful, from an

immigrant Jew like Lionel Cohen and his famous Lionel toy trains to an Austrian bodybuilderturned-millionaire actor and governor like Arnold Schwarzenegger. Carnegie arrived penniless;

Ford’s company went broke; and Lee Iacocca had to eat crow on national TV for his company’s

mistakes. Secure property rights not only made it possible for them all to succeed but, more

important, established a climate of competition that rewarded skill, talent, and risk taking.

Political skill was essential too. From 1850 to 1860 the United States was nearly rent in half by

inept leaders, whereas an integrity vacuum nearly destroyed American foreign policy and shattered

the economy in the decades of the 1960s and early 1970s. Moral, even pious, men have taken the

nation to the brink of collapse because they lacked skill, and some of the most skilled politicians in

the world—Henry Clay, Richard Nixon, Bill Clinton—left legacies of frustration and corruption

because their abilities were never wedded to character.

Throughout much of the twentieth century, there was a subtle and, at times, obvious campaign to

separate virtue from talent, to divide character from success. The latest in this line of attack is the

emphasis on diversity—that somehow merely having different skin shades or national origins

makes America special. But it was not the color of the skin of people who came here that made

them special, it was the content of their character. America remains a beacon of liberty, not merely

because its institutions have generally remained strong, its citizens free, and its attitudes tolerant,

but because it, among most of the developed world, still cries out as a nation, “Character counts.”

Personal liberties in America are genuine because of the character of honest judges and attorneys

who, for the most part, still make up the judiciary, and because of the personal integrity of large

numbers of local, state, and national lawmakers.

No society is free from corruption. The difference is that in America, corruption is viewed as the

exception, not the rule. And when light is shown on it, corruption is viciously attacked. Freedom

still attracts people to the fountain of hope that is America, but freedom alone is not enough.

Without responsibility and virtue, freedom becomes a soggy anarchy, an incomplete licentiousness.

This is what has made Americans different: their fusion of freedom and integrity endows

Americans with their sense of right, often when no other nation in the world shares their perception.

Yet that is as telling about other nations as it is our own; perhaps it is that as Americans, we alone

remain committed to both the individual and the greater good, to personal freedoms and to public

virtue, to human achievement and respect for the Almighty. Slavery was abolished because of the

dual commitment to liberty and virtue—neither capable of standing without the other. Some

crusades in the name of integrity have proven disastrous, including Prohibition. The most recent

serious threats to both liberty and public virtue (abuse of the latter damages both) have come in the

form of the modern environmental and consumer safety movements. Attempts to sue gun makers,

paint manufacturers, tobacco companies, and even Microsoft “for the public good” have made

distressingly steady advances, encroaching on Americans’ freedoms to eat fast foods, smoke, or

modify their automobiles, not to mention start businesses or invest in existing firms without fear of

retribution.

The Founders—each and every one of them—would have been horrified at such intrusions on

liberty, regardless of the virtue of the cause, not because they were elite white men, but because

such actions in the name of the public good were simply wrong. It all goes back to character: the

best way to ensure virtuous institutions (whether government, business, schools, or churches) was

to populate them with people of virtue. Europe forgot this in the nineteenth century, or by World

War I at the latest. Despite rigorous and punitive face-saving traditions in the Middle East or Asia,

these twin principles of liberty and virtue have never been adopted. Only in America, where one

was permitted to do almost anything, but expected to do the best thing, did these principles

germinate.

To a great extent, that is why, on March 4, 1801, John Adams would have thought of nothing other

than to turn the White House over to his hated foe, without fanfare, self-pity, or complaint, and

return to his everyday life away from politics. That is why, on the few occasions where very thin

electoral margins produced no clear winner in the presidential race (such as 1824, 1876, 1888,

1960, and 2000), the losers (after some legal maneuvering, recounting of votes, and occasional

whining) nevertheless stepped aside and congratulated the winner of a different party. Adams may

have set a precedent, but in truth he would do nothing else. After all, he was a man of character.

A Patriot’s History of the United States

CHAPTER ONE

The City on the Hill, 1492–1707

The Age of European Discovery