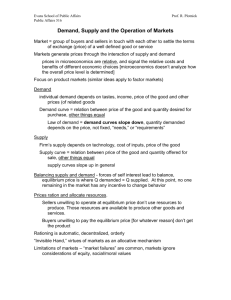

Using Laboratory Experiments to Teach Introductory Economics

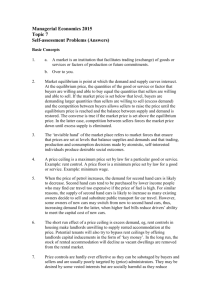

advertisement