Client project capabilities and information systems change in the

Client project capabilities and information systems change in the public sector

Jonghyuk Cha

Text-type : 5A (Research Proposal)

Topic area : Project Organising

ABSTRACT

Information systems (hereafter IS) have made a big impact on the increasing velocity of change that triggers a form of project in the public sector. For addressing the ambiguity of business and IS change, client project management capability is an indispensable factor, still less-conceptualised than the project supplier's. The objective of study is to examine client project capabilities and organisational change in IS projects in the public sector, through the theoretical lens of dynamic capability. In this context, the concept of dynamic capability will be applied to investigate the IS projects of public business. Then, the relative importance of capabilities at a different stage of IS change will also be analysed.

This study pursues mixed qualitative methods: content analysis and a case study using semi-structured interviews. In the pilot phase of the research, content analysis is used to analyse 15 project reports published by the National Audit Office in the UK during the last ten-year period reporting on 31 IS project cases in the UK public sector. The findings will be utilised to develop a research question and an interview protocol whose objectives are to make a thorough investigation about required client project capabilities. By mixing two mutually complementary methods, both historical data and contemporary phenomena can be examined that come from contents and interviews respectively; interview results can also increase the validity of reports data.

Through the final results, client project capabilities in IS project can be understood theoretically; dynamic capability can thereby be re-defined in detail from a project management viewpoint. In addition, the relative importance of client capability can increase the efficiency of its utilisation for managing project resources from a practitioner perspective. Thus, the research results will be able to improve the efficiency of developing public policy and its governance strategies for projects and programmes.

KEYWORDS

Project management, Client capability, Information systems change

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014

1. INTRODUCTION

As research background, four main issues can be outlined for this study. Firstly, the frequency of project business has been increased continuously. The changeability and complexity of business environment have accelerated the frequency of project-based works, and its proper management also has become a key agenda for organisational efficiency (Brady and Davies, 2004; Zwikael et al., 2005).

Thus, project management has become a well-established approach for encountering the ambiguity of business change.

Secondly, due to continuous information systems driven business phenomena, information systems implementation and advancement have been a significant business agenda in most organisations. At the same time, information systems and technologies have played an important role to the increasing velocity of change (Chen et al., 2009). Lyytinen and Newman (2008), for example, contend that information systems change can generate a huge influence on several aspects such as project organisations, goals, deliverables, process, and users, as well as the information systems itself.

Despite this recognition, it is widely accepted that the rate of project success is still far from certain

(Standish Group, 2009; Eveleens and Verhoef, 2010). Particularly, regardless of the progress of enormous efforts for managing projects, project escalation in resources has still occurred in the case of information systems projects (Pan et al., 2006).

Thirdly, in recent years, a number of researchers have suggested ways of improving project management capability in the public sector, across academic and industrial fields. However, it is acknowledged that the client side capability is less conceptualised than the project supplier’s. The client, which is a permanent organisation, has a difficulty of managing projects, due to a lack of proper capabilities to control the temporary project organisation (Winch, 2013). Regarding this,

Winch et al. (2012a) argue that project clients’ roles and skills for managing projects are fundamental, but are ambiguously defined, especially for managing organisation. For example, in a multiple projects environment, proactive change management of organisation and process is a key activity for managing projects and resources (Lycett et al., 2004; Winch et al., 2012b). For this reason, the more project business has become complex and diverse, the more clients’ difficulties for managing project and facilitating learning cycle have grown (Ferns, 1991; Rautiainen et al., 2000; Winch et al., 2012a).

Lastly, the ability to carry out managerial change ambiguity has become the main topic of organisations and entrepreneurs, due to a constant need for business improvement (Stevenson and

Starkweather, 2010). In this regard, various researchers have conceptualised dynamic capability further to manage resources more effectively within a view of ‘managing resources’ and ‘improving business routine’, which can be distinguished from an operational capability (Helfat et al., 2007).

To sum up, the overall aim of this research is to analyse client project management capability, especially in the case of information systems projects in the public sector. Moreover, the second objective is to find out the relative importance of client capabilities across the information systems project life cycle. The research questions, which cover the purpose of this study, are: 1) What are the essential client dynamic capabilities in information systems projects in the public sector?, and 2) Does the relative importance amongst client capabilities exist across the information project life cycle?. To find out the answers for these research questions, a few key concepts should be discussed in advance

(e.g. project clients’ managerial issues, environmental features of public sector, and the changeability of information systems). On the basis of this context, this paper will present the overall approach and detailed explanation of study, particularly on a pilot study.

2

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014

2. RESEARCH THEME

2.1 Theoretical Framework

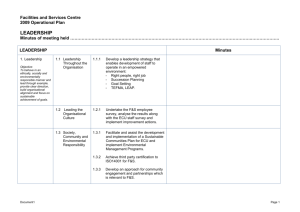

As seen in figure 1, the main research fields can be categorised into three parts: (1) Dynamic capability & public sector, (2) Project management, and (3) Information systems. Moreover, there are also overlapped research areas between them, such as project management capability, client capability in information systems environment, and information systems project.

Figure 1: Theoretical Framework

The first literature review field covers research topics about dynamic capability and the characteristics of public sector. Theoretically, the theoretical meaning of a ‘capability’ should be understood to define what dynamic capability is. To do so, the definition of capability will be investigated at first.

Then, the difference between operational and dynamic capability will be analysed. Moreover, the characteristics of public sector and client perspective will be grasped to conceptualise essential dynamic capabilities in the public sector. The second review topic aims to find out the context of project, project organisations, and its managerial issues. Recently, it is a common situation that multiple projects are executed at the same time, and they lead to an increase of organisational complexity. Moreover, not only the organisational complexity but also the high degree of information systems changeability can give rise to the expansion of project uncertainty. To carry out these issues, project organisational aspects will be studied within the view of dynamic capability (view of business change). Thus, by applying the context of business change, project management topics such as organisational complexity and structural features will be analysed. The third research subject relates to information systems business, and two main objectives for examining this field can be explained.

One is to understand the ecosystem of information systems business, and the other objective is to investigate the trends of information systems change and its life cycle. As mentioned previously, this study aims to analyse client dynamic capability for managing projects across information systems change environment. Therefore, it is essential to understand information systems life cycle and its change patterns due to constant advancement of information-driven business models.

3

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014

In addition, three overlapping research areas (4)-(6) are also identified: dynamic capability-project, project-information systems, and information systems-dynamic capability. Particularly, it is generally acknowledged that the 6 th

research area, client dynamic capability in information systems environment, has not been studied actively; therefore, it can be an initial point of research contribution.

On the basis of this structure, existing previous relevant literature can be classified by adopting the literature review diagram into 3-research fields and 3-overlapped topics. Within the perspective of research procedure, a study about dynamic capability and public sector will be carried out at first.

Then, the research about project/programme management and organisational issues will be followed in order to investigate the information systems environment, life cycle and change model.

Concurrently, the relevant literature placed at the overlapped areas will also be analysed, and they can demonstrate the understanding of contextual interrelationship amongst three research themes.

2.2 Literature review

(1) Dynamic capability & public sector

Dynamic capability

A concept of dynamic capability is placed on the flow of business change and improvement. Though, too-much-changeable business environment can regard dynamic capabilities as overhead, they still enhance the level of business change in a positive way (Winter, 2003). In this regard, keywords which can describe the characteristics of dynamic capability are ‘organisational resource’ and ‘business routine’, particularly emphasised by Eisenhardt and Winter respectively. Eisenhardt and Martin (2000) attempt to define dynamic capability on the basis of RBV (resource based view), and argue that dynamic capability can create business value by utilising organisational resources such as physical assets, strategic decisions and human resources. Meanwhile, Winter (2003) defines dynamic capability as an approach for improving business routines to react and govern the level of change of operational capabilities. According to Winter’s research, there are two types of capability based on the purpose of each capability: ordinary (operational) and dynamic capabilities. In that paper, ordinary capabilities (synonymous with operational capability) are conceptualised as firms’ abilities to ‘make a living’. Then, dynamic capabilities are explained as a concept to extend, create and modify the operational capabilities to deal with business routine change. To sum up, dynamic capability can be defined as a capacity for improving organisational routines to purposefully create, modify and extend its resources, rather than the role of operational capability which focuses on simple problem solving and job-accomplishment. Table 1 summarises the definitions of dynamic capability.

Table 1: Definitions and concepts of dynamic capability

Author,

Year

Descriptions Key Concepts

Collis, 1994 Strategic insights that derive from managerial and entrepreneurial capabilities: Govern the rate of change of operational capabilities strategy, managerial capability, change of operational capabilities

Teece et al.,

1997

The firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments reconfiguration, changing environment

Eisenhardt &

Martin, 2000

The firm’s processes that use resources to match and create market change; organisational and strategic routines by which firms achieve new resources resource, market change, routines

4

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014 configurations

Pisano, 2000 Regulate the search for improved routines

Rosenbloom,

2000

The ability to achieve new forms of competitive advantage

Zollo &

Winter, 2002

A learned and stable pattern of collective activity through which the organization systematically generates and modifies its operating routines in pursuit of improved effectiveness routine, organisation, improved effectiveness

Zott, 2003 Organizational processes and activities that guide the evolution of a firm’s resources, capabilities, and operational routines

Helfat et al.,

2007

The capacity of an organization to purposefully create, extend, or modify its resource base improved routines new forms, competitive advantage routine, resource, organisational process capacity for creation, extension and modification resource

Public sector business

Public sector business has a clear distinction in comparison to private sector business. Public business generally focuses on maximising organisational performance, whilst for-profit-strategy is a main approach in private sector. For this reason, a research about public organisation’s own strategy is one of the main subjects under investigation. Based on previous literature, key features of public sector business can be described as follow: Organisational needs, Limited accessibility for external resources, and Political influence. Firstly, the main objective of public business is to achieve certain organisation’s needs, not to maximise profit (Collins, 2005; Pablo et al., 2007). Secondly, the opportunities for accessing external resources are more limited than private business environment, and it leads public organisations concentrate more on internal resources and potential areas of expertise

(Pablo et al., 2007). In other words, internally-focused resources and related organisational performance are the key success factors for achieving the goal of project in public organisations; alternatively, they also make an attempt to organise temporal project coalition with external organisations, or to focus on managing project procurement. Thirdly, public projects are closely related to government policy and funding, and government strategies are the trigger for generating projects and their strategic change. In this regard, public sector business has higher level of changeability due to the change of policy and the imposition of short-term election cycles (Boyne,

2002).

However, there are also moves to apply business strategy of a private sector to public sector because of financial difficulties (Pablo et al., 2007). One of them, for instance, is a strategy based theory such as dynamic capability, which has been utilised in private sector with frequency. Thus, the effectiveness of managing projects in the public sector can be improved by applying the strategies of private firms whose objective is to maximise profits from limited budget. In this study, the concept of dynamic capability has been chosen as one representative example of those strategies, and it will be means to interpret information systems change projects in the public sector.

On the basis of key features of public sector business, the strategic direction of public sector business can be proposed as follow. It is acknowledged that most public organisations tend to concentrate on project procurement management due to the lack of internal development capacities; this is similar to

5

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014 the majority of SME cases. Moreover, if financial capacities are also limited as most public organisations, they have no choice but to lean on external service providers. Thus, public organisations should focus on both procurement management and capability development to deal with business change immediately.

(2) Project management

A project management has become one of well-defined approaches for facilitating business change.

Initially, it was developed from construction and aerospace industries, and also has been spread out to diverse industries including information systems. Scholars have defined the concept of project and project management, and two of the most officially established principles are PRINCE2 and Project

Management Body of Knowledge, published by the Office of Government Commerce (hereafter OGC) in the UK and Project Management Institute (hereafter PMI) in the US respectively. Based on the key publications, the concept of project and project management can be explained as table 2.

Table 2: Project and project management (Source: OGC, 2009; PMI, 2009)

PRINCE2 PMBOK

Project

(Definition)

Characteristics of project

Project management

(Definition)

“A temporary organisation that is created for the purpose of delivering one or more business products according to an agreed business case” (OGC, 2009)

Change & Uncertainty

Temporary

Cross-functional

Unique

“The planning, delegating, monitoring and control of all aspects of the project, and the motivation of those involved, to achieve the project objectives within the expected performance targets for time, cost, quality, scope, benefits and risks” (OGC, 2009)

“A temporary endeavour undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result” (PMI, 2009)

Temporary

Unique Products, Services, or

Results

Progressive Elaboration

“The application of knowledge, skills, tools and techniques to project activities to meet project requirements” (PMI, 2009)

Managerial aspects

Cost, Timescales, Quality, Scope, Risk,

Benefits

Integration, Scope, Time, Cost,

Quality, Human resource,

Communication, Risk, Procurement

A project has become more complex, and the increase of project complexity can lead to the rise of awareness and significance of success factors. Moreover, it is generally acknowledged those complexities make more significant impacts on client side than project suppliers (Flowers, 2007); a member of project can be broadly categorised by two, supplier and client. For instance, project client’s limited capabilities based on internal resources are only optimised for managing existing products and services, and they have a limitation for customising new systems development. As a result, client organisation tends to select an out-sourcing approach rather than in-house development

(Hui et al., 2008); and that approach can increase the dependency on external service providers without suitable internal capabilities.

Many researchers and industry leaders have recognised the importance of an organisational approach in terms of capability maximisation. On the basis of previous studies, one of the most significant factors of project situation is organisational understanding and capability management (Müller and

6

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014

Turner, 2007; Pines et al., 2009; Artto et al., 2011). According to Hyväri’s research (2006), the author contends that organisational conditions of projects can be divided by 5 levels: project, project manager, project team members, organisations and environment. Similarly, Manning’s (2008) approach for organisational context of projects is comprised of four major areas: projects, organisations, inter-organisation networks and organisational fields. From internal project itself to external environment, the author categorises a project-based environment within a structural perspective. In particular, Crawford (2005) found that the most considerable factors that generate project performance are ‘organisational project management maturity’, and ‘assess communications management outcomes’; more than 60% of respondents in that study were from ICT projects. Based on these approaches, a project is a part of certain organisations, and then a project should be generated and managed by an organisational viewpoint by recognising structural context and affiliated human resources.

In addition to the significance of organisational aspects, a project has a certain life cycle. Patel and

Morris (1999) demonstrate that a life cycle model can make a unique difference with non-projects.

However, project life cycle has become more complex because of managerial diversity (Smith, 2007).

Regarding this, PMI (2009) states that “Project managers or the organization can divide projects into phases to provide better management control with appropriate links to the on-going operations of the performing organization” (PMI 2009, p19). Therefore, it can be a crucial factor to understand a structural big picture, relationships between each stage, certain objectives, and milestones.

(3) Information systems

According to the development of information based society, information systems and technologies have changed and improved the entire organisations, industries, and their business patterns rapidly.

Even though similar terminologies, such as information systems (IS), information technologies (IT), and information communication and technologies (ICT), still have been used ambiguously, most entrepreneurs have recognised the importance of this paradigm; and they have made a huge effort to understand and deal with the information driven emerging markets (Heeks, 2008; Perez, 2009).

In regard to this stream, not only the information itself but also the related process and environment have been converted digitally by the whole business actors (Perez, 2009). In the case of banking industry, for example, customers are already familiar with using the Internet or mobile service to use the service, and banking service providers manage their clients and relevant information by developing customer relationship management solution and enterprise resource planning systems.

Besides, the advancement of information systems development is also able to accelerate the velocity of change of tasks, organisational structure, and actors as well as the technological change itself

(Lyytinen and Newman, 2008). These transitions have led to more vigorous development paradigm, and information systems based business has become an inevitable trend for societies to create the competitive advantages from individuals to companies and even nations (Madon et al., 2009).

For this research, this section will mainly be focused on understanding the context of information systems environment. In advance of that, conceptual clarification amongst IS, IT, ICT will also be carried out.

(4) Project management capability

Project management needs proper capabilities to drive it successful and more efficient by focusing on specific goal-directivity. Müller and Turner (2010) assert that competences have a direct corelationship with the measurement of project success. Likewise, capabilities can drive project

7

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014 performance which make an impact on project success (Crawford, 2005; Morris et al., 2006). Thus, managerial capability can be a critical success factor of project. In this regard, Müller and Turner

(2007) also claim that every project manager should be assigned to suitable projects within a view of management capabilities. Meanwhile, Brady and Davies (2004) emphasise the significance of project management capability for carrying out ‘business change’. The authors develop a theoretical model which covers the relationship between organisational learning and project capabilities. The research model describes how project capabilities can be built through the organisational learning process, and this PCB (Project Capability Building) model mainly focuses on a specific situation that a firm moves into ‘new technology and market bases’.

In terms of business terminology such as ‘capability’ and ‘competency’, there are still ambiguous use of two terms across academic and industrial fields (Stalk et al., 1992; Javidan, 1998). Though a few researchers, in the field of strategy or innovation research, suggest differentiated views between two concepts, they are still unclearly used across the project management studies. Therefore, the clear meaning of capability should be defined on the basis of contextual meaning in advance of examining this section without theoretical confusion (e.g. individual vs. organisational, and knowledge/skill vs. relative competitive competitiveness).

To sum up the context of project management capability in section (2) and (4), the three key features,

‘internal resources’, ‘project complexities’ and ‘organisational perspective’ can be the main characteristics of project management in terms of capability facilitation. Researchers demonstrate the importance of users’ perspective in innovation process and related project management. Furthermore, it is true that the majority of research focuses on project supplier’s side. In other words, a research about capability and resource facilitation from project client viewpoint is insufficient, and it should be carried out in-depth.

(5) Information systems project

In order to develop or change new information systems, the form of project has been recognised as one of the most suitable approach in recent times. Especially in the public sector, information systems and relevant technologies have become a key element to deliver more efficient services (Currie, 2012).

In the case of UK NHS IT programme, for instance, clients' level of expectation for services now has increased to involve actively in their health management (Mark, 2007). In general, various issues such as systems change, high technology capital goods and operational information technology infrastructure have been covered through the information systems projects (Pellegrinelli, 1997). In this regard, the importance of organisational considerations has been recognised as the most significant managerial factor, whilst the successful implementation of systems and technologies was important traditionally (Newman and Robey, 1992). Thus, many researchers have examined the information systems project in the public sector within multiple perspectives including organisations, strategies, and politics. Currie (2012) interprets the NPfIT (National Programme for Information

Technology in the UK) by applying the concept of institutional isomorphism theory, and Newman and

Robey (1992) see information systems development as a social process.

In spite of the recognition of influence of organisational aspects in the context of information systems project, managerial difficulties still have escalated. A few characteristics of the information systems environment lead to the difficulties for developing and managing those projects. For example, Davies and Hobday (2005) emphasise the complexity of information systems project by developing the concept of ‘Complex products and systems’ (e.g. customising hardware and software to be fitted with certain organisational conditions). We can find out those difficulties easily by the NPfIT, the largest

8

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014 and the most controversial IT project across the world. In that case, though the main objective of programme is to develop new information systems, the hardest project conflicts are generated from organisational factors. Currie (2012) argues that managerial conflicts amongst several stakeholders mainly occurred because of their efforts to retain existing professional dominance. In order to understand these problems more structurally, Leavitt (1965) suggests socio-technical change model to identify relationships between structure, people, technology and task and their effects on information systems projects. Then, Lyytinen and Newman (2008) re-interpret the model by emphasising the gap between structure and technology.

As explained above, the main point of information systems project is not a technology but organisational aspects. Therefore, it is essential to recognise and understand impacts of information systems on various elements including organisational factors. To carry out this study, capabilities for managing projects will mainly be focused on organisational viewpoint as well as technological issues.

In addition, those capabilities will also be interpreted through the concept of information systems change life cycle (variances of relative importance within process viewpoint).

(6) Client dynamic capability in information systems environment

As mentioned previously, several issues generate difficulties for developing, facilitating and managing capabilities in information systems environment in the public sector: e.g. complexity of public business, diverse stakeholders, and political changeability (Boyne, 2002; Currie and Guah,

2007). In other words, it is essential to research about dynamic capability in public sector business to deal with information systems, less-studied in both academia and industries. On the basis of findings, characteristics between ‘information systems projects in the public sector’ and ‘the context of dynamic capability’ can be explained by three keywords: Internal resources, Organisational value, and

Business change. At first, both concepts regard internal resources as a critical value for business implementation. Secondly, organisational performance is a key objective for developing and managing dynamic capabilities and public sector projects. Lastly, in the case of public sector business, government policies drive business change, and dynamic capability also focuses on business routine change/improvement to advance business process and resources more efficiently. Therefore, both dynamic capability and public IS projects should be understood within a context of internal resource, organisational approach, and its performance. Resultingly, dynamic capability in the context of project management in the public sector can be defined as ‘an ability to facilitate ‘business change and improvement’ through managing ‘internal resources’ to achieve project goals in the public sector.

Based on the framework, most topic areas excluding section (6), ‘Client dynamic capability in information systems environment’, have been studied constantly. Thus, this study will be conducted by investigating both previous literature (1)-(5) and contributable new research area (6). Each part will be investigated more thoroughly to find out expected initial results as the list below.

(1) Dynamic capability in the public sector : Definition and context of dynamic capability, key features of public sector business

(2) Project management : Project management context, significance of organisational approach, project supplier/client viewpoints, life cycle model

(3) Information systems : Industrial characteristics of information systems, conceptual clarification of IS, by comparing with IT and ICT

(4) Project management capability : Essential capabilities for managing projects, client perspective project capability

9

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014

(5) Information systems project : Key features of information systems development and change in project management environment, organisational issues in IS

(6) Client dynamic capability in information systems environment : Client capabilities for managing IS, relevance between capabilities and information systems change (i.e. relative importance of capabilities across information systems change life cycle)

3. METHODS & PROCESS

3.1 Approach and process

This research pursues a qualitative approach in terms of a methodology. In addition, this study adopts two research methods; content analysis as a pilot study, and a semi-structured interview based case study. Documentary data such as National Audit Office (hereafter NAO) reports have been explored to identify current initiatives/status of the UK government information systems projects. The findings will be used to develop an interview protocol whose objective is to make a thorough investigation about required client capabilities in public organisations. The interviews also aim to find out the relationship between client project capabilities and information systems change.

The rationales for selecting two methods can be asserted as follow. Both historical and contemporary data can be collected. NAO reports are generally composed of a record of past events, and the case study will be conducted by analysing current projects. Moreover, interview results from project practitioners can increase the validity and reliability of data gathered from NAO reports. Thus, both approaches can be mutually complementary methods. Furthermore, balance between research depth and breadth can be retained by adopting a case study and content analysis respectively. In addition to the grounds for the mixed approach, the rationales for selecting each method will also be explained at the section 3.2 Methods: Pilot (content analysis) and case study.

Figure 2: Research process and the coverage of data collection/analysis

10

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014

Figure 2 describes the research process for this study. Before collecting data, defining research questions and reviewing relevant literature should be carried out in advance in order to conceptualise what kinds of data is certainly required and how those data can be interpreted. Based on this process, currently both literature review and a pilot study have been carried out. Particularly, the NAO reports, published during the last ten-year period, have been investigated to collect the information about the

UK government’s information systems project initiatives and current status. Moreover, the patterns of public sector project and required capabilities also have been examined. After this pilot study, the semi-structured interview based case study will be carried out to achieve the aim of this study thoroughly. The detailed progress of pilot study and case study plan will be explained at the next section.

3.2 Methods: Pilot study (content analysis) and case study

(1) Pilot study

In general, the origin of content analysis method was established from quantitative approach to find out the frequency of words and categories (Kebede, 2012; Krippendorff, 2013). However, unlike the natural scientific method, social science is more concerned with meanings and intentions of textual contents (Krippendorff, 2013). A few researchers also emphasise the significance of qualitative content studies to understand the context of quantitative data and their formulation (Schreier, 2012).

For example, Berelson (1952, p114) demonstrates that “a great number of non-numerical content studies call for attention by virtue of their general contribution in insight and interest”. Similarly,

Kracauer (1952) asserts that too much quantification of data can give rise to the inaccuracy of analysis.

Thus, more theoretical and context-based qualitative research can complement the limitation of quantitative content analysis.

As explained at the previous section, NAO reports have been piloted by applying a content analysis method. The NAO reports are produced by the National Audit Office, and are reviewed by Public

Accounts Committee in the UK. Thus, the reports have validity and reliability as official data, and they can be one of the most optimised information to analyse public sector business. Currently, there are 1,456 NAO reports available, and they are classified by 27 categories provided by NAO

(http://www.nao.org.uk/, accessed in January 2014). Amongst them, 39 reports, published in the category of “ICT and systems analysis”, have been chosen for this analysis. In this set, only one report has been excluded as it was released in 10 February 1984, regarded as old and non-validated data

(data collection range: 1 January 2004 ~ 31 December 2013). 38 reports are, again, categorised by 5types: “Case”, “Legacy IT Service”, “Policy”, “Auditing Report”, and “Progress Report”. The main purpose of this re-categorisation is to identify whether the reports cover public project case or government ICT policy. In the type of “Case”, 15 reports are identified as “Case (analysis report)”; though there are 16 reports, exactly same paper is published twice with different name. 15 reports cover the information about 31 UK public ICT project cases; the lists of reports are as figures 3. In order to identify and investigate research data more structurally, Nvivo 9 software has been utilised.

By adopting the qualitative analysis software, it offers more integrated and visualised functionalities that help the efficiency of data collection and analysis (Davidson and di Gregorio, 2011).

On the basis of this approach, the characteristics of public sector service and information systems projects can be found. Moreover, the ICT projects initiatives and their attributes in the UK can also be examined. By collecting those data, the characteristics of client dynamic capabilities in terms of public ICT projects can be investigated.

11

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014

Figure 3: Selected 15 NAO reports

(2) Case study

On the basis of data from the pilot study, an interview protocol can be developed to apply the case study method. In order to examine this study, a case study method will be applied as the main way of qualitative research approach. Using case studies has become one of the most challenging methods across all social science endeavours (Yin, 2003; 2009; Flyvbjerg, 2011). Nevertheless, case studies are widely utilised in business and organisational studies due to its remarkable characteristics (Mason,

2002; Silverman, 2005; Stake, 2005). For example, by adopting a case study method, more diverse and in-depth data can be collected than other methodologies, and it is suitable for investigating organisational phenomena and contexts (Stake, 2005; Flyvbjerg, 2011).

In the case of this research topic about project management and dynamic capability, a few features seem to be a consensus in relation to the concept of case studies. First of all, a project is a specific event of business organisations (organisational study). Secondly, the research theme, project management, is comprised of the form of specific organisations only for a certain project, not for an ordinary enterprise organisation (in-depth case). Thirdly, across professional industries, various projects have had difficulties of managing their project capabilities so that case data can be influenced by the real social phenomena (social study). In other words, a case study method can be appropriate for understanding organisational context and phenomena as social science studies.

In this research, a case study approach can be carried out by two aspects: documentary analysis and a semi-structured interview. The documents of project organisations should be covered to understand projects’ context more theoretically (Mason, 2002; Flick, 2006). Documents can be instructive to investigate the real society in institutional contexts (Flick, 2006). In the case of this study, more practical and empirical information, reflected the actual business environment, can be acquired by documentary analysis. For example, the current status of ICT projects initiatives and environmental features in the UK can be found. However, documental information should be reviewed on the basis of agreement of accessibility, as accessing the data is extremely confidential to the organisations

(Flick, 2006).

By adopting the interview method, the specific situations and action sequences in project organisations can be investigated in detail (Silverman, 2005; Flick, 2006). The major aim of interview is to understand the perspective of interviewees and grounds of their recognition (Bryman, 2004). In addition to the individual interview approach, group-based interview and discussion are also suitable for understanding organisational context and collecting data more precisely (Steyaert and Bouwen,

12

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014

2004). In regard to my research, a project is composed of organisational factors, and their communication capability is one of the most critical aspects. Thus, a project is a collection of group works, and most of them are processed by certain organisations, not by individuals. In this case, the recognition of interviewees in a focused group in terms of project capability can be reflected and emphasised more efficiently. Moreover, a discussion amongst them is also able to confirm individual ideas by themselves, and to remind themselves of their organisational issues from previous projects within more practical views. Furthermore, it is efficient to understand the actual project life cycle of the UK public ICT projects.

4. RESULTS & EXPECTED FINDINGS

4.1 Interim results

By using Nvivo 9 programme, all paragraphs of 15 NAO reports are coded. Basically, each paragraph is coded into one node; a few sentences are also coded into two or more nodes if those have multiple implications. Resultingly, approximately 1,600 paragraphs have been coded into 201 nodes. As shown in table 3, there are five root nodes as tier-0. Each root node is 3 tiered (tier 0, 1, and 2), and tier-2 nodes are shown in detail in figure 4, 5, and 6.

Table 3: Root nodes and tier-1 nodes

Tier-0 node

(Root node)

Node 1. Project Management in Practice

Tier-1 node

Node 2. Information Systems Business

Node 3. Public Sector Project

Node 4. Case Description

Node 9. ETC (e.g. Foreword)

Contract Management

Management Approach

Organisation Management

Planning & Change Management

Quality Management

Risk Management

Context of Information Systems

Control & Support

Data Management

HR & Organisation

Technology

External Factors

Government & Policy

Public Management Approach

Public Private Partnership

31 nodes by each project case

Miscellaneous

Node 4 is comprised of general descriptive information such as background, objective, and budget/cost/schedule of 31 UK public ICT projects. However, a few paragraphs or sentences in node

4 are also coded into node 1-3, if they are recognised as significant information. To organise them more structurally as a reference data set, only node 4 is coded with 4 tiers. As a pilot study, therefore, node 1, 2, and 3 are the main body of content analysis, whilst the data in node 4 is used as reference.

Figure 4, 5, and 6 show the hierarchy of node 1, 2, and 3 respectively: “Project management in practice”, “Information systems business”, and “Public sector project”. First of all, six tier-1nodes are generated and 357 references (paragraphs) are coded into node 1 as described in figure 4. Above all,

13

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014

140 references are coded into the tier-1 node “Organisation management” as the most coded tier-1 node in the node 1; amongst 15 reports, 12 reports are mentioned about the significance of organisation management and relevant issues. It can be interpreted that most of the UK ICT projects discussed in the NAO reports, emphasise more on organisational values; such as the importance of governance structure, managerial responsibility, and stakeholder involvement. Besides, a majority of reports also depict the changeability of project (74 references are coded); e.g. scope creep, cost creep, requirement & contractual change.

Figure 4: Node 1 - Project management in practice

Second, 370 references are coded into node 2: Information systems business. Amongst tier-1 nodes,

“HR & Organisation” is chosen as the most frequent value (133 references are coded). Similar to the interim result from the node 1, organisational values are also regarded as the most significant aspect for managing project. For example, the issues about “End user requirement & engagement”,

Knowledge & experience”, and “Training & skill” are emphasised in this node. In addition to this, the second most frequent value is “Technology” which means the significance of technological issues such as software functionality and system integration. From the whole 15 reports, 11 and 7 reports give a description with regard to “HR & Organisation” and “Technology” respectively. It is an intriguing result that organisational issues are more commonly discussed rather than technological ones in information systems business. In other words, it can be acknowledged that the most significant aspect of managing projects is to manage human resources and organisation as well as technological aspects. In similar to this context, an IT project is explained as business/process change in 41 paragraphs, not just achieving technological mission. Figure 5 shows the overall results of coded data in the node 2.

14

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014

Figure 5: Node 2 - Information systems business

Third, in the case of node 3: Public sector project, 102 references are coded from 8 reports and main features are discovered. In similar to the results from literature review, a few analogous characteristics of public sector projects have been found. First, public sector projects are strongly driven by government policy. For this reason, the changeability of public sector projects is very high due to the revocation of policy or political change. Second, they are highly influenced by external factors such as global standards and environmental regulation. For instance, the standardisation of chip design and data formats was the key agenda of UK’s e-Passport project to conform to the requirements from

International Organization for Standardization and European Union. Third, Public-Private-Partnership

(hereafter PPP) is a very common business pattern as collaboration. On the basis of PPP approach, the government can increase the post-usability of ICT project deliverables by obtaining the opportunity of commercialisation. Furthermore, expertise and best practice from private sector projects can enhance the efficiency of managing government projects.

Figure 6: Node 3 - Public sector project

15

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014

According to the interim results from node 1, 2, and 3, common features such as the importance of organisational aspects can be found; for instance, “Governing structure, process & staffing”, “End user requirement & engagement”, and “Public private partnership & collaboration”. In other words, it can be interpreted that how well a project is organised is a key criteria for determining the capacity of project management. In this regard, the clients as a permanent organisation can be in a managerial trouble more easily when they deploy a temporary project organisation. Thus, “project organising is best seen as a configuration of permanent organisations coming together to form a temporary coalition to deliver a particular outcome” (Winch 2013, p8).

Based on this theoretical approach, currently organisational dynamic capabilities and relevant issues have been studied more specifically by analysing the piloted results. All of 15 reports have been analysed as a pilot study, and the overall results will be infra-knowledge for preparing semi-structured interview procedure.

4.2 Expected empirical findings

Based on the two research methods, a set of dynamic capabilities can be collected by investigating empirical findings. Moreover, the variances of dynamic capabilities across the life cycle can be investigated. Summing up, research flows from literature review to content analysis and case study can be summarised as table 4: The relationship between literature review, research methods and research outputs.

Table 4: Expected empirical findings

… Methods Literature Review Pilot Study

Output

Type

Initial

Findings

Research outputs

Dynamic capability in project management context

Environmental features/properties of client/public sector

Characteristics of ICT project management

ICT project life cycle

DC & PS PM IS NAO report

Analysis

● ●

● ●

● ●

● ●

●

●

Information systems change model & organisational impact

ICT project initiatives and current status in the

UK public sector

Expected

Results

A set of client project capability

Variances of capabilities across IS project life cycle cf.

●

: Very relevant,

○

: Relevant

○ ● ●

●

○

Case Study ……

Document

Analysis

Semi-structured

Interview

○

●

●

●

●

●

○

●

●

●

○

○

●

●

16

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014

5. CONCLUSION

Again, the aim of this study is to analyse a client project management capability by adopting the concept of dynamic capability in context of information systems related business change. The initial research question is: “What are essential client dynamic capabilities in information systems project in the public sector?”. In terms of methodological approach, the results of relevant literature review will support to develop research framework, and content analysis and case study methods will be applied.

The expected results are: 1) the conceptualisation of client project capability (information systems project and dynamic capability), 2) a set of dynamic capability, and 3) variances of those capabilities with respect to the level of significance across the information systems change life cycle.

This study will provide theoretical and practical contributions, and both academics and practitioners will benefit from the research. Above all, client dynamic capability in the context of information systems driven public project can be understood theoretically. Recently, it is acknowledged that there is a lack of research about dynamic capability across project management research. Based on the contextual similarities between two (i.e. concept of business change and internal resource-based approach), dynamic capability can be re-defined in detail within project management viewpoint. In this regard, moreover, a research about public sector business is less-activated than private sector business. Resultingly, this research will be able to generate an original contribution theoretically.

The relative importance of client capability can facilitate the efficiency of capability utilisation upon managing resources of public projects within the practical perspective. Though every capability is significant and efficient in terms of managing projects, each capability has more relativity to each phase of project life cycle (or information systems change procedure). By finding out the interrelationship between a capability and each phase of the life cycle, public sector organisations can make more concentration on allocating their resources and capabilities to specific project stages; this approach can develop the optimised way of managing projects and relevant capabilities. Thus, the results about variances of capabilities will be able to improve the efficiency of developing public policy and its governance strategies.

17

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014

REFERENCES

Artto, K., Davies, A., Kujala, J. & Prencipe, A. (2011). The project business: Analytical framework and research opportunities In: Morris, P. W. G., Pinto, J. K. & S derlund, J. (Eds) The oxford handbook of project management, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 133-153.

Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in communication research, New York: Hafner Publishing.

Boyne, G. (2002). “Public and private management: What’s the difference?”. Journal of Management

Studies, 39, 97–122.

Brady, T. & Davies, A. (2004). “Building project capabilities: From exploratory to exploitative learning”. Organisational Studies, 25, 1601-1621.

Bryman, A. (2004). Social research methods, (2nd Edition), Oxford University Press.

Chen, C. C., Law, C. & Yang, S. C. (2009). “Managing ERP implementation failure: a project management perspective”. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 56:1, 157-170.

Collins, J. (2005). Good to great and social sectors, Boulder, CO: Jim Collins.

Collis, D. J. (1994). “How valuable are organizational capabilities?”. Strategic Management Journal,

15, 143-152.

Crawford, L. (2005). “Senior management perceptions of project management competence”.

International Journal of Project Management, 23, 7-16.

Currie, W. L. & Guah, M. W. (2007). “Conflicting institutional logics: a national programme for IT in the organisational field of healthcare”. Journal of Information Technology, 22:3, 235-247.

Currie, W. L. (2012). “Institutional isomorphism and change: The national programme for IT - 10 years on”. Journal of Information Technology, 27:3, 236-248.

Davidson, J. & di Gregorio, S. (2011). Qualitative research and technology in the midst of a revolution, In: Denzin, N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds) The sage handbook of qualitative research.

(4th Edition), Sage Publications, 627-643.

Davies, A. & Hobday, M. (2005). The business of projects, Cmabridge University Press.

Eisenhardt, K. M. & Martin, J. A. (2000). “Dynamic capabilities: What are they?”. Strategic

Management Journal, 21:10/11, 1105-1121.

Eveleens, J.L. & Verhoef, C. (2010). “The rise and fall of the Chaos report figures”. IEEE Software,

27, 30-36.

Ferns, D. C. (1991). “Developments in programme management”. International Journal of Project

Management, 9:3, 148-156.

Flick, U. (2006). An introduction to qualitative research, (3rd Edition), Sage Publications.

Flowers, S. (2007). “Organizational capabilities and technology acquisition: Why firms know less than they buy”. Industrial and Corporate Change, 16:3, 317-346.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2011). Case study, In: Denzin, N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds) The sage handbook of qualitative research. (4th Edition), Sage Publications, 301-316.

Heeks, R. (2008). “ICT4D 2.0: The next phase of applying ICT for international development”.

Computer, 41:6, 26.

Helfat, C. E., Finkelstein, S., Mitchell, W., Peteraf, M., Singh, H., Teece, D. & Winter, S. G. (2007).

Dynamic capabilities: Understanding strategic change in organizations, Blackwell, Malden MA.

Hui, P. P., Davis-Blake, A. & Broschak, J. P. (2008). “Managing Interdependence: The Effects of

Outsourcing Structure on the Performance of Complex Projects”. Decision Sciences, 39:1, 5-31.

Hyväri, I. (2006). “Success of projects in different organizational conditions”. Project Management

Journal, 37:4, 31-41.

18

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014

Javidan, M. (1998). “Core Competence: What Does It Mean in Practice?”. Long Range Planning, 31:1,

60-71.

Kebede, E. (2012). The application of transaction cost economics to UK defence acquisition, PhD,

The University of Manchester.

Kracauer, S. (1952). “The challenge of qualitative content analysis”. Public Opinion Quarterly, 16:4,

631-642.

Krippendorff, K., (2013). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology, (3rd Edition), Sage

Publications.

Leavitt, H. J. (1965). Applied organisational change in industry: Structural, technical and humanistic approaches. In: March, J. G. (Eds) Handbook of organisation, Rand McNally, Chicago, IL, 1144-

1170.

Lycett, M., Rassau, A. & Danson, J. (2004). “Programme management: A critical review”.

International Journal of Project Management, 22, 289-299.

Lyytinen, K. & Newman, M. (2008). “Explaining information systems change: A punctuated sociotechnical change model”. European Journal of Information Systems, 17:6, 589-613.

Madon, S., Reinhard, N., Roode, D. & Walsham, G. (2009). “Digital inclusion projects in developing countries: Processes of institutionalization”. Information Technology for Development, 15:2, 95-

107.

Manning, S. (2008). “Embedding projects in multiple contexts - A structuration perspective”.

International Journal of Project Management, 26, 30-37.

Mark, A. (2007). “Modernizing Healthcare - Is the NPfIT for purpose?” Journal of Information

Technology, 22:3, 248–256.

Mason, J. (2002). Qualitative Researching, (2nd Edition), Sage Publications.

Morris, P. W. G., Crawford, L., Hodgson, D., Shepherd, M. M. & Thomas, J. (2006). “Exploring the role of formal bodies of knowledge in defining a profession - The case of project management”.

International Journal of Project Management, 24, 710-721.

Müller, R. & Turner, R. (2010). “Attitudes and leadership competences for project success”. Baltic

Journal of Management, 5:3, 307-329.

Müller, R. & Turner, R. (2007). “The influence of project managers on project success criteria and project success by type of project”. European Management Journal, 25:4, 298-309.

Newman, M. & Robey, D. (1992). “A Social Process Model of User-Analyst Relationships”. MIS

Quarterly, 16:2, 249-266.

Office of Government Commerce. (2009). Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2, The

Stationery Office, ISBN 978-0-11-331059-3.

Pablo, A. L., Reay, T., Dewald, J. R. & Casebeer, A. L. (2007). “Identifying, Enabling and Managing

Dynamic Capabilities in the Public Sector”. Journal of Management Studies, 44:5, 687-708.

Pan, S. L., Pan, G. S. C., Newman, M. & Flynn, D. (2006). “Escalation and de-escalation of commitment to information systems projects: Insights from a project evaluation model”.

European Journal of Operational Research, 173:3, 1139-1160.

Patel, M. B. & Morris, P. G. (1999). Guide to the project management body of knowledge. University of Manchester, UK: Centre for research in the management projects.

Perez, C. (2009). “Technological Revolutions and Techno-Economic Paradigms”. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 34:1, 185-202.

Pines, A. M., Dvir, D. & Sadeh, A. (2009). “Project manager-project (PM-P) fit and project success”.

International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 29:3, 268-291.

19

Doctoral Colloquium, EURAM2014

Pisano, G. P. (2000). In search of dynamic capabilities: The origins of R&D Competence in

Biopharmaceuticals, In: Dosi, G., Nelson, R. R. & Winter, S. G. (Eds) The nature and dynamics of organizational capabilities. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 129-154.

Project Management Institute. (2009). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, (4th edition), Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, Inc.

Rautiainen, K., Nissinen, M. & Lassenius, C. (2000). “Improving multi-project management in two product development organizations”. Proceedings of Hawaii International Conference on System

Sciences.

Rosenbloom, R. S. (2000). “Leadership, capabilities, and technological change: The transformation of

NCR in the electronic era”. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 1083-1104.

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice, Sage Publications.

Silverman, D. (2005). Doing qualitative research, (2nd Edition), Sage Publications.

Smith, C. (2007). Making Sense of Project Realities: Theory, Practice and the Pursuit of Performance,

Hampshire: Gower Publishing Limited.

Stake, R. (2005). Qualitative case studies, In: Denzin, N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds) The sage handbook of qualitative research. (3rd Edition), Sage Publications, 443-466.

Stalk, G., Evans, P. and Shulman, L. E. (1992). “Competing on capabilities: The new rules of corporate strategy”. Harvard Business Review, 57-69.

Standish Group. (2009). The Standish group CHAOS report 2009. Standish Group International.

Stevenson, D. H. & Starkweather, J. A. (2010). “PM critical competency index: It execs prefer soft skills”. International Journal of Project Management, 28:7, 663-671.

Steyaert, C. & Bouwen, R. (2004). Group methods of organizational analysis, In: Cassell, C. M. &

Symon, G., (Eds) Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research, London:

Sage Publications, 140-153.

Teece, D., Pisano, G. & Shuen, A. (1997). “Dynamic capabilities and strategic management”.

Strategic Management Journal, 18, 509-533.

Winch, G., Leiringer, R. & Lindsrtom, M. (2012a). “Client capability: Towards a research programme for the public sector”. Proceedings of the 12th European Academy of Management Conference.

Winch, G., Meunier, M., Jead, J. & Russ, K. (2012b). “Projects as the content and process of change:

The case of the health and safety laboratory”. International Journal of Project Management, 30,

141-152.

Winch, G. (2013). “Three domains of project organising”. International Journal of Project

Management, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.10.012.

Winter, S. G. (2003). “Understanding dynamic capabilities”. Strategic Management Journal, 24:10,

991-995.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Applications of case study research, (2nd Edition), Sage Publications.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case Study Research: Design and methods, (4th Edition), Sage Publications.

Zollo, M. & Winter, S. G. (2002). “Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities”.

Organization Science, 13, 339-351.

Zott, C. (2003). “Dynamic capability and the emergence of intraindustry differential firm performance:

Insights from a simulation study”. Strategic Management Journal, 24, 97-125.

Zwikael, O., Shimizu, K. & Globerson, S. (2005). “Cultural differences in project management capabilities: A field study”. International Journal of Project Management, 23:6, 454-462.

20