Enterprise Project Management Office

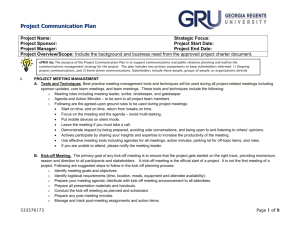

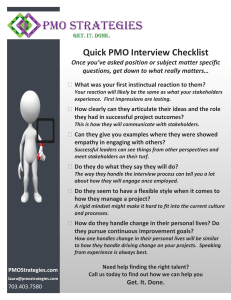

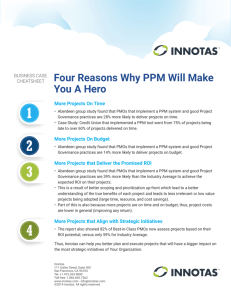

advertisement