The Influence Factors of Dynamic Capabilities

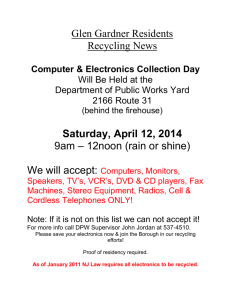

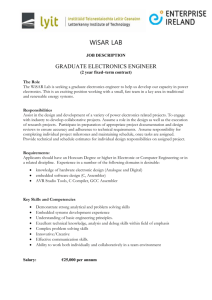

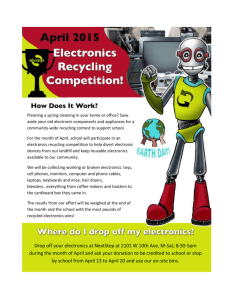

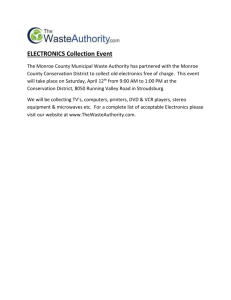

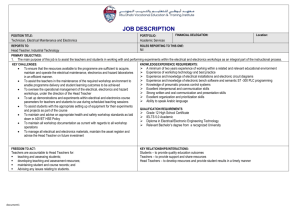

advertisement