Econ - WWI

advertisement

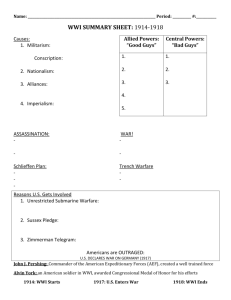

2013 2014 19 YE AR S DO I NG EDITION OU RB EST , SO ECONOMICS ECONOMICS Economics of World War I RESOURCE EDITOR ALPACA-IN-CHIEF Tania Asnes Daniel Berdichevsky ® the World Scholar’s Cup® YO U CA N DO YO UR S ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 1 Table of Contents An Economic History of World War I ....................................................................................................2 A War Was What He Got .................................................................................................................. 2 The Domi-Oh-noes Fall..................................................................................................................... 2 Europe Mobilizes ............................................................................................................................... 3 Great Britain ................................................................................................................................... 4 France ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Italy................................................................................................................................................. 5 Russia .............................................................................................................................................. 5 America Steps In ................................................................................................................................ 5 1. The Sinking of the Lusitania ....................................................................................................... 6 2. The Sinking of the Sussex ............................................................................................................ 6 3. The “Sussex Pledge” (And How to Break It) ............................................................................... 6 4. The Zimmerman Telegram ......................................................................................................... 7 America Gears Up… ....................................................................................................................... 7 ... Mans Up... .................................................................................................................................. 7 ...and Moves Out ............................................................................................................................ 8 Supporting the War at Home............................................................................................................. 8 The War Industries Board ............................................................................................................... 9 The Food Administration.............................................................................................................. 10 The Railroad Administration ........................................................................................................ 10 The Fuel Administration ............................................................................................................... 11 The War Cost How Much? .............................................................................................................. 11 Direct Costs of the War ................................................................................................................ 12 Indirect Costs of the War .............................................................................................................. 13 How Are We Going To Pay For All This?........................................................................................ 15 Mom, Baseball, Apple Pie, and Debt ............................................................................................. 15 British War Financing (or “Tea and Crumpets and Debt”) ........................................................... 16 C’est La Debt ................................................................................................................................ 16 War Financing in Deutschland ..................................................................................................... 17 Wartime Economic Performance ..................................................................................................... 18 Misleading Numbers ..................................................................................................................... 18 The United States Economy.......................................................................................................... 19 The British Economy .................................................................................................................... 19 Economic Contraction Elsewhere.................................................................................................. 19 Normal Again .................................................................................................................................. 19 German Recovery (Such as it Was)................................................................................................ 20 Long-Term Effects of the Great War................................................................................................ 21 The Ratchet Effect ........................................................................................................................ 21 Who Put America in Charge? ........................................................................................................ 21 What Happens To The Money? ....................................................................................................... 21 Un-Keen Keynes ........................................................................................................................... 22 Conclusion ....................................................................................................................................... 23 About the Author ................................................................................................................................25= ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 2 An Economic History of World War I When (spoiler alert) recently crowned King Joffrey ordered Ned Stark beheaded, he wanted to demonstrate his power. Did he, even for a second, stop and consider, “What will happen if I go through with this?” Or even, “Am I going to trigger a giant, brutal, bloody rebellion?” No. He gave the order and ignored the baffled looks on everyone’s faces as the executioner carried it out. That single decision, that one act of violence, produced continent-wide consequences—a long and costly war with Ned’s followers that took no one but Joffrey by surprise. A similar situation unfolded in Sarajevo on July 28, 1914, but with one crucial difference1: when an assassin shot and killed Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand, a massive war was exactly what he wanted—and what almost no one else expected. A War Was What He Got While starting a war may have been Bosnian-Serb student Gavrilo Princip’s goal, he may not have realized how massive a conflict his gunshot would ignite. Long-standing alliances and mutual defense treaties escalated might have been a simple clash between Austria-Hungary and Serbia into a prolonged war involving nations around the globe. “I aimed at the Archduke. I do not remember what I thought at that moment.” Gavrilo Princip The war brought about unprecedented destruction. 70 million soldiers fought in the field, and 9.4 million died—either from injuries sustained in battle, or from secondary causes such as disease and infection. The death toll was greater than that in all the wars of the hundred years before it combined. It was, if not a war to end all war, a war unlike all wars. Its name, the Great War 2, was wholly earned. For the first three years, America remained neutral, but when it entered the conflict in April of 1917, it did so decisively: two million American soldiers crossed the Atlantic to the front in France. Nearly 1.4 million saw direct combat on the war’s front lines. 114,000 never came home 3. The Domi-Oh-noes Fall In a vast, lethal chain reaction, the assassination of a single political figure4 drew what seemed like the entire planet into war. The alliances that made this outcome inevitable were, ironically, originally meant to help keep the peace in the face of rising political tensions 5 in Europe. 1 Just one. Everything else was exactly the same. Before it had a sequel, at least. 3 And at least one (or most of one) went to hang out in Spain. 4 And his wife. It is a little-known fact that Sofia had the nuclear codes. 5 Too much yeast. It is known. 2 ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 3 England and France were old, wealthy, established powers, the acknowledged political and economic elite of the European continent. They were like a pair of veteran champion show dogs 6; they had been winning the shows for so long that most viewers considered it a given that they would keep on winning. Germany was more a young, fierce pup that had been getting steadily stronger, and whose owner decided the champion dogs had won for long enough. Germany wanted to challenge the status of those international elder statesmen. Its rapid advances made the British and the French very nervous—so nervous that they decided it would be prudent to secure some help, just in case the Germans tried to prove their superiority by force. An alliance took shape between England, France, and Russia, which would eventually come to be known as the Allied Powers. Germany came to a similar agreement with Austria-Hungary and Italy, a group of nations that would be referred to as the Central Powers. These alliances and smaller ones of the same ilk set the stage for the war to spread across the European continent and, eventually, to include the United States. Like a series binge watching frenzy on Netflix, it all unfolded over the course of just eight days: One month after Ferdinand’s death, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. Germany, allied with Austria-Hungary, declared war on Serbian-allied Russia. Because Russia was allied with France, Germany declared war on France as well. In one 24-hour period, Germany extended its declaration of war to Belgium7, and French-allied England declared war on Germany. In all of this, economic considerations played a vital role. They affected the buildup, and influenced the fighting itself. In turn, the war influenced the world’s economics for decades to come. Europe Mobilizes When a country goes to war, its economy changes radically. A country whose most popular export is telescopes will have an economic structure that revolves around telescopes: its factories and craftsmen will manufacture them, many of its businesses will sell them, and a good chunk of its population will make their living, one way or another, based on telescopes. If that country goes to war, everything must change, since telescopes won’t have much of an effect on enemy troops (other than identifying them). Suddenly, the country must shift to making guns, ammunition, bombs, tanks, armored alpacas, and airplanes—and 6 7 Or a certain California Academic Decathlon team. The Belgians looked up from their waffles and scarcely had the time to say, “Who, us?” before they were bratwurst. ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 4 those few businesses already making goods useful to the war effort find themselves vastly expanding their output. Undertaking such a shift is called mobilization—a term some use to refer to gathering soldiers for battle, but also refers to gearing up an entire economy. The European countries involved in the Great War went about mobilization in different ways. Great Britain Right out of the gate, Great Britain and Germany did their best to prevent each other from mobilizing. Britain leveraged its powerful navy to impose a massive trade blockade on Germany. The Germans had a far smaller fleet, but swiftly deployed one of their new inventions, the U-boat (submarine) to attack British ships—not only in an effort to bust open the British blockade of Germany, but also to establish a German blockade of Great Britain8. The United States was still neutral at this point, and had been exporting goods to Germany for many years; Britain’s effective blockade meant it was cut off from a significant source of revenue, and American business owners protested, loudly and often. Great Britain refused to budge. At home, Great Britain turned its massive internal resources to the war effort. It had amassed great wealth over hundreds of years, and, by the year 1917, fully 40% of its annual economic output would be funneled into the conflict. Its steel industry saw an immediate increase, growing by 25% over the course of the war. Its munitions output also grew, but not quickly enough to suit the British government. The Ministry of Munitions stepped in, said words to the effect of, “Thanks, but we’ll take it from here,” and took direct control of what they considered “key industries” such as railways and coal mines. Despite this government-mandated focus on the war effort, the coal industry’s output dipped, its production falling throughout the war. Too many miners had simply left to become soldiers. France It could be argued that France was the hardest hit of any European nation involved in the Great War. Even counting the Eastern Front, the lion’s share of the combat9 took place on French soil, causing the country massive physical damage.10 This shock carried over into the French economy. Given no choice but to assemble an army as rapidly as possible, France mobilized a first wave of more than 5 million men in August1914. Most of these soldiers had been pulled from jobs in private industry, so even as France cobbled together a decent-sized army, these soldiers left their jobs vacant or filled by inexperienced replacements, including women, children, and those few men physically unable to serve in the military. This dramatic shift in the labor force did the French economy no favors. Government spending rocketed from 10% in 1913 to 53.5% in 1918. 8 This blockade was never as effective as the British blockade of Germany, in part because Germany didn’t have enough Uboats and Britain had too many ports—the joys of island-hood, along with endemic species and more charming fishing villages. 9 And the staring at one another while not combatting. 10 In other words, the French countryside got beaten like a heavy bag in Mike Tyson’s gym. ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 5 Italy In 1913, Italy was not a big economic dog like England and France 11, and its ability to respond with troops, equipment, and other wartime necessities was limited. Once Italy committed to joining the Entente, however, it had no choice in the matter: it had to mobilize. The government quickly took control of the Italian war effort, with a two-tiered structure of command: The Supreme Committee of Ministers was ultimately responsible for the mobilization… …while the Under-Secretariat for Arms and Munitions oversaw day-to-day production. Because of Italy’s limited resources, the government gave its private industries firm marching orders: they were forced to manufacture goods for use by the armed services. A few of Italy’s industries benefited disproportionately: mechanical engineering and hydroelectricity companies saw great gains, and one particular car company (FIAT) surged ahead of its competitors. Unfortunately, the spotlight placed on those few industries, and the outsized resources channeled to them, meant other Italian industries suffered. Russia When the war started, Russia had a few substantial advantages and a few even greater disadvantages. In the advantages column, Russia was (and still is) enormous.12 If Italy was a scrappy little dog, Russia was a sled team of Huskies. Its land mass and its population dwarfed those of the other European nations, and its ability to produce agricultural resources was unmatched. The disadvantages column was much telling, unfortunately. It started with the state of Russia’s economy, which most European countries considered “backwards.” Though Russia’s population greatly outnumbered those of the other combatants, its income per capita was low. The average Russian earned somewhere between 11% and 30% of what the average American did. And the same size that made it such a tremendous nation made it a difficult one in which to move goods and soldiers around in an efficient way. These shortcomings translated directly into Russia’s difficulties organizing and mobilizing its population. Russia eventually poured 24% of its annual national income into supporting the war effort, but never achieved as much as countries a fourth its size. In 1917, the Central Powers defeated Russia. Unable to transport or supply its military effectively, and caught up in the throes of political revolution, it had no choice but to withdraw from the conflict. America Steps In Until April 16, 1917, the United States had remained neutral in the Great War. Achieving and maintaining that neutrality was easier for the United States than, say, for Belgium: the entire Atlantic Ocean stretched out between it and Europe. Debate it! Resolved: That the United States should have entered World War I earlier than it did. It was, ironically, a series of incidents involving traffic on that same Atlantic which ultimately brought America into the war, with the deal sealed by a single unwise telegram. It all unfolded in four distinct stages: 11 12 More like a scrappy entry in the “toy” category. At the time, this was the Russian Empire, after all. ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 6 1. The Sinking of the Lusitania The RMS Lusitania was a massive British ocean liner—not as big as the Titanic, but still huge13. It was a passenger ship, but had also agreed to carry supplies for Great Britain. Since Germany had declared the waters around the British Isles an open war zone, it considered the Lusitania fair game. On May 7, 1915, a German U-boat struck the Lusitania with torpedoes, sending it to the bottom of the ocean. More than a thousand people downed. Ordinarily, Americans would have considered this just one more tragedy of the war in which they wanted no part—except that, on this particular voyage, the Lusitania was carrying American passengers. 159 of them (or 128, depending on the source) were among the dead. News of this massacre at sea outraged the American public. 2. The Sinking of the Sussex Taking their blockade of the British Isles very seriously, another German U-boat fired on the Sussex, a vessel the German navy suspected of laying mines. In reality, the Sussex was a French ferry boat, designed to transport passengers across the English Channel. It carried no mines 14. The badly damaged ferry managed to limp into a French port, but at least fifty of its passengers died in the attack, and twenty-five Americans were injured. Helped along by colorful journalism, the American public’s anger at the German attacks grew, and more and more began demanding a military response. President Woodrow Wilson, doing his best to keep America out of the war, instead issued a sternly-worded warning to the Germans: “Unless the Imperial Government should now immediately declare and effect an abandonment of its present methods of submarine warfare against passenger- and freight-carrying vessels, the Government of the United States can have no choice but to sever diplomatic relations with the German Empire altogether.” (emphasis added) In other words, “Hey! Quit attacking unarmed ships with your submarines, or we’ll give you the official cold shoulder. Seriously, we won’t even talk to you anymore.” The warning was much less than many Americans wanted, but was a step closer to engaging in the war. 3. The ‘‘Sussex Pledge’’ (And How to Break It) In response to President Wilson’s warning, the Germans made a two-part promise that became known as the “Sussex Pledge”: Germany would no longer attack completely non-military (i.e. passenger) vessels. Germany would still attack merchant vessels, but only after searching them and giving their crew safe passage back to land15. For most of 1916, the Sussex Pledge seemed to accomplish what President Wilson intended. As the war continued, however, the tide began to turn against the Germans (and that British naval blockade just absolutely refused to go away)—so in 1917 Germany decided to modify the Sussex Pledge unilaterally. 13 A movie about the sinking of the Lusitania might only be about three hours long, but it would have a cooler antagonist. Although it did carry a few yours. 15 Such courtesy. 14 ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 7 By “modify,” we mean “disregard entirely.” Germany declared its new policy concerning ocean-going vessels was to attack every ship it encountered with great gusto. In March of 1917 alone, the German navy sank five American ships. 4. The Zimmerman Telegram All of this rampant sinking of American ships might have been enough to lead the United States to sigh wearily and enter the Great War—but any lingering hesitation was neatly16 resolved on March 1, 1917. “Never before or since has so much turned upon the solution of a secret message.” David Kahn, author of The Codebreakers, describing the Zimmerman telegram Back in January of that year, British intelligence had intercepted a telegram sent from the German Foreign Minister to the German Minister to Mexico. Decoding it revealed a stunning message: Germany had asked Mexico not just to join the Central Powers 17, but to march on the United States. If it went to war, Germany would help it recapture some of the territories it had lost over the previous century—including the future Academic Decathlon hubs of Texas and Arizona. The telegram’s translated contents were released to the American press on March 1, and, without further recourse, the United States formally declared war on Germany and all its allies 18 on April 6. America Gears Up… Following Russia’s defeat and withdrawal, the war in Europe had mostly ground to a halt, as the opposing sides faced a stalemate. Now that President Wilson had officially declared war, the United States faced the same task that the rest of the combatants had faced years earlier—namely, how to convert the American economy from peacetime to wartime. The same factor that had made neutrality easier now presented an epic obstacle: the Atlantic Ocean. Getting millions of men from one shore to the other proved one of the key considerations in the American war effort.19 ... Mans Up... The American involvement in World War I lasted from April 6, 1917 to November 11, 1918. During that time, the bulk of American servicemen were in the Army, numbering approximately 4 million. An additional 800,000 men served in the country’s other armed services, including the Marines and the Navy. Combat Training In general, American soldiers who saw combat in France were trained for six months before shipping out, and then another two months once they had arrived in Europe. The United States military knew it needed to establish a forceful presence in the European theater as quickly as possible. To ensure that it could mobilize enough troops, it passed a new measure into law: a draft. Officially known as the “Selective Service” law, the draft required all male United States citizens 16 As triggers for war go, a telegram is a lot less bloody than, say, the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Its joining would have stretched the definition of “Central” about as far as it could go. 18 Mexico, probably wisely, had declined to become one of these allies—otherwise the United States would have had its hands full on its southern border. 19 From continent to shining continent, with an ocean in between. 17 ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 8 ages eighteen to forty-five to sign a national registry. Once registered, anyone signed up could be “drafted,” or compelled to serve in the military. This kind of compulsory service is also known as conscription. In sum, 24.2 million men signed up for the Selective Service; 2.8 million were drafted and sent to war. ...and Moves Out A daunting logistical issue faced the American military in 1917: how does one transport millions of soldiers across an ocean as quickly as possible? Debate it! Resolved: That compulsory military service for all able-bodied citizens is preferable to occasional implementation of a lottery-based draft. The answer was not “fly them there”—military transport aircraft did not exist20. The military needed ships, lots and lots and lots of ships, and they needed them, as the saying goes, “yesterday.” 21 Daunting as this task was, the United States quickly secured the ships it needed. Roughly half came from the British—who were more than happy to loan them over—with a few more coming from other allies. The remainder were manufactured the Emergency Fleet Corporation, an entity that sprang into existence ten days after America’s declaration of war on Germany. The United States Shipping Board, a governmental agency designed to oversee maritime affairs, had created it out of a necessity. In the words of the Board’s chairman, Edward N. Hurley: “When the United States declared war against Germany the whole purpose and policy of the Shipping Board and the Fleet Corporation suffered a radical change overnight. From a body established to restore the American Merchant Marine to its old glory, the Shipping Board was transformed into a military agency to bridge the ocean with ships and to maintain the line of communication between America and Europe.” The Emergency Fleet Corporation did its job brilliantly, supplying the war effort with more than 2,000 vessels—nearly a million tons’ worth—for transport across the Atlantic. Combined with the ships already delivered, this gave the United States military roughly two million tons of fleet. “But hang on,” some of you may be thinking. “The German U-boats were sinking ships left and right. How was this enormous fleet of American ships supposed to reach Europe without getting torpedoed?” The answer was “surprisingly well”—perhaps because of the heavy toll the war had already taken on the German U-boats. The hastily-assembled American fleet transported a rough total of 7.5 million tons of cargo. It lost only 200,000 tons during the entire trans-Atlantic trek, and only 142,000 tons of that went to the bottom because of torpedo attacks.22 Supporting the War at Home The task of transporting well-equipped, well-trained troops across an ocean was only one of many challenges involved with joining the war. The United States also had to settle on ways to convert its peacetime economy into one dedicated to supporting the war effort. The task of accomplishing this was divided between several newly-created governmental agencies. 20 And you would still need a lot of planes. Or sooner, if possible. 22 In your FACE, U-boats! 21 ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 9 The War Industries Board Placed in charge of obtaining the materials and products the country would need for the war effort, the War Industries Board (WIB) was first instated in July of 1917—and, after churning through two chairmen (Frank A. Scott and Daniel Willard), was completely reorganized in March of 1918 under the leadership of financier Bernard M. Baruch.23 With that somewhat tumultuous nine-month period behind it, the WIB settled into its primary task: deciding what prices the government would pay for strategic goods such as coal, lumber, and steel. In a free market, prices are determined by supply and demand; at its most basic, the more consumers buy something, the less of it there is available, and the more valuable it becomes. Hence, its price goes up. The War Industries Board could not easily operate by this principle. The government had become a single, gigantic, needy customer, which needed to get its hands on war-related goods in the fastest, most efficient way possible. There were at least three possible approaches to this. The WIB could have: Set one price high enough that all manufacturers, even the most costly, could profit. Set different prices for purchases from each manufacturer, according to its costs. Set a price such that some manufactures could profit and others could not. Debate it! Resolved: That it is unethical for businesses to profit from war. The WIB settled on a version of the third option, which it termed bulk-line pricing. Consider lumber. Every business in the country that produces lumber will have a different cost. At one end are companies such as the supersized MegaLumber Corporation, which owns enormous, high-tech, industrialized lumber mills and can produce a ten-foot plank for about 80 cents. At the other end is Mom-and-Pop, Inc., a little wife-andhusband sawmill operation. The wife goes out each morning, cuts down a tree herself, and brings it home to the tiny mill in their backyard, where her husband spends all day cutting up the tree. Because of the time and effort this takes, the cost for Mom-and-Pop to produce one ten-foot plank is a much higher $4.00.24 The MegaLumber Corporation can charge $3.00 per ten-foot plank and make a very tidy profit of $2.20 per plank. Mom-and-Pop, would have to charge at least $4.01 per plank to make any profit at all. 23 24 Presumably while Scott and Willard sat around and pouted. Their slogan is, “Each plank is cut with love!” ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 10 The WIB reasoned it could get all the goods it needed for the war effort by buying from the 80% of the manufacturers with the lowest costs (the “bulk” of the manufacturers). It set a single price for each unit, just high enough for 80% of an industry to turn a profit from the government purchases. The highest-cost businesses, such as Mom-and-Pop, were still free to sell to other customers at their normal prices, but they missed out on the lucrative government contracts handed out to their more efficient competitors. In a free market, prices increase as demand increases, and higher prices tempt suppliers to find more ways of making a good. With the bulk of the industry’s prices fixed in place, however, as demand increased, producers whose costs were already close to the government price would run out and see no incentive to increase output, causing shortages. To help manage shortages, the WIB came up with a ratings system, applying different priorities to different goods. The system had five levels: AA, A, B, C, and D. “AA” meant, “Get this done as fast as humanly possible,” and “D” meant, “Eh, whenever you get around to it.” The Food Administration In an approach very different from that taken by the War Industries Board, the Food Administration relied on voluntary cooperation. Created in August of 1917 through the Lever Food and Fuel Act, its head, Herbert Hoover, would infamously go on to become president in 1929. Rather than step in and set prices, Hoover’s Food Administration chose a softer tactic: persuasion and propaganda. It asked businesses and the public to help the war effort by voluntarily cutting back on their consumption of certain products. To that end, the Food Administration launched massive marketing campaigns promoting such concepts as “Meatless Mondays” and “Wheatless Wednesdays” and preaching that giving up these products on specific days was an act of patriotism. The Food Administration could then channel more of the selected products to troops at lower prices. The agency’s tactics were not limited to persuasion. It also provided licenses to food processors and distributors, and, if a businesses were found in violation of a rule, it could revoke the appropriate licenses—or threaten to do so, in exchange for concessions. The Railroad Administration If we measured “governmental influence on private business” on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being least influence and 10 being most, the War Industries Board would probably have rated around a 6 or a 7. With its gentler persuasion techniques25, the Food Administration might have lagged at 3 or 4. The Railroad Administration registered a solid 10, and would have hit 11 if the chart went that high. 25 Also known as guilt trips. My mother would have made an excellent Food Administration consultant. ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 11 The railroads did not start out at a 10—in fact, in the years leading up to World War I, they were a veritable disaster. Simply put, there was too much traffic and too little cooperation. Tracks had become so congested they could not effectively transport products needed for the war effort. Nor could they effectively transport troops. When the many different railway companies involved failed to cooperate to clear up the congestion, President Wilson put his foot down: he would make adjustments for them. In 1917, he nationalized the country’s railroads: all the railroad companies, which up to that point had been privately held businesses, were abruptly and completely taken over by the government. According to author William J. Cunningham, before the war the privately-held rail companies had not been making enough money to lay much-needed new tracks and build new stations. The increase in wartime use had added to the congestion, compounding existing problems. Once the railroads were nationalized, their efficiency skyrocketed. Carrying troops was given a higher priority than carrying goods, and the Railroad Administration moved approximately 616,000 troops each month. That impressive logistical accomplishment required 13,912 trains dedicated solely to transporting soldiers on journeys of over 800 miles. The nationalization of the train system had its critics, but, as far as the war effort went, it was a coup. The Fuel Administration Taking a page from the War Industries Board, the Fuel Administration engaged in no-nonsense price fixing—but with a much narrower focus. As far as the United States was concerned at the time, “fuel” meant “coal.” The Fuel Administration’s mission was to make sure coal remained available to the war effort. As such, it set the prices of coal right at the mines (without waiting for it to be transported to various sellers). It also worked with the Railroad Administration to ensure coal reached the proper destinations. The Fuel Administration lasted from 1917 until 1919, when it was officially abolished. 26 The War Cost How Much? Figuring out how much World War I cost different countries is difficult because the costs go beyond their direct spending on the war efforts. Some of the costs they incurred—such as lost and ruined lives—are very hard to quantify. Consider a hypothetical soldier named Jim. Jim went to France, where he was killed when he shot himself by mistake getting off a plane27. What if Jim had lived? If the war had never started, would Jim have gone to college, patented an amazing new shoelace, started a company, and become wealthy? Today, we might even refer to tying our shoelaces as “jimming28 our shoes”, and his company might have employed hundreds of people. Or he might have spent the rest of his life pumping gas at a service station and bowling on Wednesdays—contributing to the economy relatively little, but still raising a family that loved him. All that uncertainty makes computing the cost of war very difficult, and is the reason that the “capitalized value of war deaths” in the “Indirect Costs of World War I” chart below have to be estimates. 26 Presumably with a sound not unlike the protracted deflating of a balloon. It happens. I know, because I saw it in the movies. 28 Much to the distress of Jim’s company, people would use the term “jimming” even for off-brand shoelaces. 27 ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 12 Direct Costs of the War The direct costs of the war were fairly straightforward. The “gross cost” column in the “Direct Costs” chart represents the actual sum of money each participant in the war spent. Bear in mind, however, that the wealthier members of each alliance also loaned cash to their allies. These loans were called advances. We have to subtract the loan amounts from the gross total, or our numbers would be off—we would be double counting the loan and the spending of the loan. The “net cost per capita” is the net cost—the amount spent, minus advances loaned out—divided by a country’s population. Therefore, Great Britain spent $766 net cost per capita, or $766 per person in Britain. In fact, it spent more than any other combatant—even more than France, a bit surprising given that far more combat took place on French soil. In order from highest-spending per capita to least-spending: 1. Great Britain: $766 2. France: $613 3. Germany: $557 4. Austria-Hungary: $352 5. Italy: $343 6. United States: $229 The United States did spend less than the others on the list, but its financial stake was still considerable; $229 represented about a third of the average American citizen’s annual income of $745 in 1919. (Adjusted for inflation, that $745 in 1919 would be $10,055.00 today—and $229 would be $3,090.) ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 13 Indirect Costs of the War If the direct costs were all we had to consider to calculate, we would be bored now.29 Sadly, as the ghost of poor Jim could tell you (if ghosts were willing to discuss economics), the task is not that simple. The indirect costs of the war included, among others: Property loss Shipping & cargo loss Lost production War relief The deaths of soldiers and civilians Opportunity Cost When you have a choice between doing A and B, and you choose A, the opportunity cost is what you would have gotten if you had done B. If you have the option of spending your Saturday afternoon washing your movie star friend’s pet pig—for which he will pay you ten dollars—or hanging out with your friends, and you choose to hang out with your friends, that enjoyable social time just cost you ten bucks. We also need to consider opportunity costs when we try to estimate the indirect costs of all the above. When a nation’s economy shifts from peace to wartime, it puts most of its energy into producing weapons, gear and other necessities—when it could have been spending on health care, clothing, and Xboxes. The loss of those Xboxes is a hidden cost—indirect, and impossible to quantify with 100% accuracy—but it is a real loss, and cannot be ignored. 29 And could spend the rest of the day watching Buffy reruns. ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 14 As far as historians and scholars have been able to calculate, taking into account both concrete direct and estimated indirect costs, World War I cost about $337.85 billion. They have also estimated World War I resulted in military deaths equal to 1% of the population of all the involved nations. The defeated Central Powers suffered much greater losses than the Allied Powers. Serbia was hit the hardest, losing 5.7% of its military. All told, the Central Powers lost an average of 2.6% of their soldiers, the Allies a relatively modest 0.7%. If we take all the people killed in a war, plot out how many years they were likely to have lived based on average life expectancy, and multiply that figure by the average national income, the result is a reasonable guess at how much money the deceased would have generated in the economy over the rest of their lives. This capitalization of those lost in the war is the origin of the values in the first column in the “Indirect Costs of World War I” chart. There is another factor we must consider in capitalizing the loss of life in World War I. One dollar deposited in the bank today is worth more than one dollar deposited a year from now, because, over the course of that year, the first dollar can accumulate interest. We need to include this potential interest when determining how much a lost life could have earned. Economic historians Stephen Broadberry and Mark Harrison, taking additional factors into account, have arrived at slightly different conclusions.30 They recommend: Distinguishing between stock (quantity at a given time, such as the number of deaths in Germany in 1914) and flow (quantities over a period of time, such as how many men Germany lost per year) Converting of all nominal values to constant prices, so different years can be added together Remembering for human capital calculations that people consume as well as produce Noting that, while birth rates did surge postwar, the loss of human capital was still significant Acknowledging that technological change and social spending stimulated by the war had a positive impact on intangible physical capital Accounting for these factors offer us a more precise look at the loss of both human and physical capital, as demonstrated in the chart above. While the war cost France more than any of the other Allies, if we calculate the losses in a different way, as a percentage of each country’s assets, Russia was hit the hardest. Before the war, Russia’s economy was already weak, and the level of its pre-war stock was exceptionally low—meaning whatever it lost was a larger percentage of what it had. 30 Somewhat unfairly, since Bogart is no longer around to defend himself. ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 15 How Are We Going To Pay For All This? Economically speaking, a war is like an unexpected bill. Its direct and indirect costs are massive, and combatant nations must figure out how to pay for them. The three most popular methods are: Borrowing Taxation Printing of money31 The combatants in World War I all embraced the first two methods, to varying degrees. The third option was an American specialty32. Mom, Baseball, Apple Pie, and Debt The United States paid for the war effort primarily by borrowing money—chiefly from its own citizens. The government sold individual loans that people made to the government, called war bonds or “Liberty Bonds”. The process breaks down thusly: 1. A citizen buys a Liberty Bond for a certain amount—say $25.00. The bond has a fixed percentage of interest, and is redeemable at a certain date in the future. 2. Between when the citizen buys the bond and the date the bond is redeemed, that bond acts like a tiny little loan from the citizen made to the government. 3. The citizen redeems the bond after the set date, and gets back the $25.00 plus the fixed amount of interest. The Liberty Bonds did not work exactly as the government intended; the typical American citizen did not yet trust this new method of supporting the war. As it turns out, banks and other financial institutions, which saw them as a good investment, bought the bulk of the bonds. The government sold “Liberty Bonds” in four different waves, or issues: First Liberty Loan: April 24, 1917, at 3.5% interest. Total value of $5 billion. Second Liberty Loan: October 1, 1917, at 4% interest. Total value of $3 billion. Third Liberty Loan: April 5, 1918, at 4.5% interest. Total value of $3 billion. Fourth Liberty Loan: September 28, 1918, at 4.25% interest. Total value of $6 billion. This all begs the question: if the government needed to borrow to pay for the war, where could it find the money to pay back bondholders when they redeemed their bonds? Further Reading For additional details on how the War Revenue Act, affected America, visit: www.history.com/this-day-in-history/war-revenue-act-passed-in-us The answer was entrusted to another new government agency, one responsible for the nation’s banking policy. Often called “the Fed,” the Federal Reserve is essentially the central bank of the United States. 31 32 I wish I could do this when I got an unexpected bill. Like apple pie. And Apple. ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 16 One of the perks of controlling a country’s banking policies is the lawful ability to print new money. /33 This ability allowed the Federal Reserve to print cash and deposit it, paying for all those bonds and their accrued34 interest. It could also sell new bonds, using revenues to pay for old bonds being redeemed. The United States raised additional war money by revamping the country’s tax structure. For most of the nation’s history before the Great War, there had been no income tax. President Abraham Lincoln had imposed one during the Civil War, but the Supreme Court had later found it unconstitutional. Only in 1913 had the constitution been amended—the Sixteenth Amendment—to allow a new federal income tax. The wartime government saw the freshly-authorized federal income tax as a way to obtain funds for the war, and raised tax rates substantially with the War Revenue Act. The increased income tax generated $7.6 billion, covering approximately 24.5% of the country’s total war expenditure. All told, U.S. spending and financing in World War I can be summarized as such: War Expenditures Taxes Borrowing Creating New Money Total (Billions) - $31.0 + $ 7.6 + $19.0 + $4.4 Percent 100.0% 24.5% 61.4% 14.1% British War Financing (or ‘‘Tea and Crumpets and Debt’’) Unwilling to print new money, Great Britain focused only on taxation and borrowing—but it took extreme approaches to both. Great Britain embraced debt financing so thoroughly that, by 1918, it owed 127.5% of what it produced that year. All of the goods and services that it turned out in 1918 added up to £5.866 billion, yet its national debt was £7.481 billion.35 Britain did not simply watch this debt accrue; it tried to repay it in a variety of ways, including instruments similar to Liberty Bonds—although these just created a different sort of debt, like a credit card balance transfer. It issued such bonds in 1914, 1915, and 1917. It went on to borrow other sums, in both shortand long-term loan structures, from other lenders, including the United States. Great Britain also tried to raise money by increasing taxes on its citizens. Taxes levied in the first year of the war covered only about 40% of the cost of mobilization, but, as the war continued, direct taxation played a growing role. Property taxes and income taxes rose sharply, and the country began levying especially heavy taxes on alcohol, tobacco, tea, automobiles, and musical instruments36. These sorts of taxes, on certain designated items, are known as excise taxes. C’est La Debt The French relied on debt financing to fund the war effort—somewhat similar to England’s approach, with one important extra factor: France was eyeball-deep in debt even before the war. In 1914, the French 33 “Abracadollars!” Also arguably accursed. 35 Ouch. 36 (in an interesting commentary on what British citizens valued most highly in the early 20 th century) 34 ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 17 national debt stood at 65% of its Gross Domestic Product 37. This did not stop France from borrowing money, though its initial efforts focused on short-term, rather than long-term, debt. When it became apparent that the Great War was going to be long, the French government shifted to long-term debt financing strategies. It began issuing long-term debt, much like Liberty Bonds, in 1915, and continued issuing more every year through 1918. By 1916, France’s national debt had reached 124% of its GDP, rivaling England’s predicament. While the United States and Great Britain embraced taxation as a way to pay for the war effort, the citizens of France thoroughly opposed that approach. The French people were widely, staunchly, and thoroughly opposed to raising taxes, and made that opinion known throughout the halls of government. As a result, French income taxes barely increased at all.38 Blocked from raising income taxes, France enacted an Debate it! “extraordinary war profits” tax in 1916. As we covered in the section on Bulk-Line Pricing, government-set prices Resolved: That the French citizens were right to resist increases in income taxes during the war. can lead to certain manufacturers raking in much higher profits than they would on the free market. This new tax targeted those businesses. Unfortunately for France, the extraordinary war profits tax came too late in the war, and did not offset any of its costs until after the war had ended. Despite the French people’s resistance to tax increases, they began to feel an “indirect tax” effect as the war progressed. This effect was caused by inflation. “Inflation taxation” relies on three simultaneously occurring factors: The supply of money in the economy grows very quickly. The prices of goods and services in the economy quickly increase. The average citizen’s income fails to keep pace with the money supply and price increases. If these three things occur, it creates a sharp drop in the average citizen’s ability to purchase goods and services—his or her purchasing power. This effect acts like a tax. Between 1915 and 1919, France’s money supply rose 20% on average each year, and prices rocketed at an average of 19.7%. The government had to try to stabilize the economy while focusing on the war effort; it tried to stop the inflationary explosion with a series of price controls, but the effort proved futile. War Financing in Deutschland Germany exited the war not only defeated, but with a wrecked economy that was about to get even worse. It had engaged in debt financing even more than Great Britain, borrowing money to pay for a full 81% of its wartime expenditures—which, by 1917, amounted to well over half of the nation’s total spending. It was a nation at war with nothing left in its wallet. Worse yet for Germany were the inflationary effects. Prices doubled between 1914 and 1917 while the total supply of money quintupled—driving further price increases in the years that followed. Between 1920 and 1923, Germany experienced hyperinflation that crippled its economy. This hyperinflation was so 37 38 Building the Eiffel Tower must have been expensive. And raised, to use a technical term, “diddly-squat” for the war effort. ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 18 detrimental to the German people that many questioned the competency of their government. It is a common historical theory that Germans’ vast postwar suffering and resentment opened the door to new, more radical political leaders. In this way, the economics of World War I helped pave the way for the rise of Adolf Hitler and his militant Third Reich39. Wartime Economic Performance In measuring an economy’s performance, the most common metric is Gross40 Domestic Product—the total value of all goods and service produced in an economy in a given period of time. As you may remember from the basic economics guide, there are two common ways to calculate an economy’s GDP: to tally the total of all expenditures or the total of all income. Wartime GDP can be misleading. Production skyrockets in a war, as manufacturers produce vast sums of military goods (such as weapons), services (such as transportation), and food rations for deployed soldiers. If a country suddenly experiences a boom41 in the production of bullets, grenades, and missiles, GDP will appear to increase significantly. There is a difference, however, between the production of grenades and the production of consumer goods such as cars. If a country’s production of cars increases, people will purchase those cars, drive them around the country, and park them in driveways, garages, and mall parking lots. The cars’ owners choose to buy them to increase their quality of life, since the cars improve their mobility and access to jobs and other opportunities. The cars might have negative externalities (such as pollution) but they are broadly a positive force: they are goods used to create. It is a different story if a country’s production of grenades increases. Grenades are not meant to increase anyone’s quality of life, other than that of soldiers who might survive a battle by using them. Ideally, a grenade is thrown at an enemy, explodes (killing the enemy), and is gone. If unused, it is stored in a weapons locker and benefits no one42. The resources used to manufacture that grenade are not being used to manufacture cars, or anything else that might contribute to a lasting increase in quality of life 43. Those employed to manufacture them earn money they can spend elsewhere, but the grenades remain a broadly negative force: they are goods used to destroy. Misleading Numbers Mobilization may cause a nation’s GDP to appear to grow during a war, and sharp increases in prices can make it look as though income and expenditures have also risen. If an economy’s chief export is gold watches, the real value of that economy’s GDP depends on how many gold watches its manufacturers assemble and sell. If the price of those gold watches suddenly leaps from $100 to $500—but the number sold remains the same—it creates an artificial increase in the GDP. To offset this, economists adjust GDP 39 And the very terrible sequel to the war. It’s not really all that gross. Centipedes are way grosser. 41 Sorry, couldn’t resist. 42 Except, arguably, weapons locker manufacturers. 43 Such as alpaca finger puppets and delicious tisanes. 40 ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 19 to account for price inflation. The table to the right examines the wartime “real” GDPs of Great Britain, the United States, Germany, Austria, Russia, and France. Each country’s GDP starts at a base level of 100; the numbers for each year are percentages of that initial level. The United States Economy A critical difference between the United States GB US G e rm a ny Au s t ri a R us s ia F ra nc e and every other combatant is that the United 1913 100 100 100 100 100 100 States was neutral for the war’s first three years. 1914 92.3 101 85.2 83.5 94.5 92.9 It not only avoided conflict—it exported goods 1915 94.9 109.1 80.9 77.4 95.5 91 (and made loans) to the Allies. Between 1914 and 81.7 76.5 79.8 95.6 1916 108 111.5 early 1917, the United States enjoyed steady 1917 105.3 112.5 81.8 74.8 67.7 81 profits and experienced few losses. It had been in 1918 114.8 113.2 81.8 73.3 63.9 a recession before the Great War, but its early role as a supplier led to a period of prosperity that lasted through its entry into combat. It is impossible to know what the impact on the American economy might have been had it entered the war in 1914, but, because of its neutral status44 through most of the conflict, the United States definitively came out ahead. The British Economy Despite Great Britain’s amassing enormous debt over the course of the war, its GDP showed no ill effects in the long run. The British economy contracted between 1913 and 1915, but its economy had turned a corner by 1916 and continued expanding for the rest of the war. Even taking into account the decline of the GDP in the war’s early years, between 1913 and 1918, Britain’s GDP expanded by roughly 15%. Economic Contraction Elsewhere Germany and Austria, chief among the losing Central Powers, both experienced massive downturns in their GDPs—but two of the Allied Powers suffered even greater economic losses. Russia had entered the war as its poorest participant, and the beating it took did nothing to improve that situation. By the time of Russia’s withdrawal from the war in 1917, its GDP had dropped to 70% of its level in 1913. France’s GDP declined even more sharply, plummeting to 64% of its 1913 figures by 1918. Normal Again Once the war had ended, all the nations involved faced the conundrum of how to revert economies dedicated to war back into economies suited for peacetime prosperity. Debate it! Resolved: That employers should be required to give returning soldiers their jobs back. The United States brought home its soldiers as early as possible, and in enormous numbers. Two million had been demobilized by April of 1919, and, by the summer of 1920, four million American soldiers had returned to the labor force. At first, it appeared that all of these young men returning to the jobs they had vacated would lead to an unemployment problem. As feared, their rapid influx was a shock to the labor market, and the economy entered a brief downturn. But, almost before anyone could notice, the economy abruptly boomed again—fueled not by individual consumers, but by the government, which was still spending profligately.45 For one, it had to distribute 44 45 That’s “Lawful-Neutral” for all you Dungeons & Dragons™ players. You should see the size of its typical pizza delivery. ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 20 the $60.00 bonuses it had guaranteed each returning soldier, plus pay to bring all those soldiers home. In 2013 dollars, the bonus amounted to about $1187.00 per soldier. There were international costs as well; the United States To Recap began loaning money to its allies, many of which were Right after the war, individual Americans behaved struggling to recover—a total of roughly $2 billion. frugally and saved their pennies46. The government, Those funds did not stay far from home for long; the majority were immediately used by European nations to on the other hand, engaged in tremendous economic transactions, loaning out billions of dollars and buy exports from the United States. The countries of earning billions from foreign sales. Central and Western Europe, especially France, had sustained massive damage in the war, and buying American goods helped them in the rebuilding process. American businesses used the country’s post-war economic boom to focus on expansion. Manufacturers of goods expected to last for at least three years, such as cars and kitchen appliances, found themselves prospering. Consumers warmed to the thought of purchasing these durable goods, and the spread of that mindset helped inspire the consumption-rich period known as the “Roaring Twenties.” German Recovery (Such as it Was) Profound effects of the war in Germany stemmed from the loss of human capital. Varying sources quantify the economic toll differently, but the least optimistic of these estimates places Germany’s GDP in 1919 at roughly 55% of its 1913 pre-war level. The loss of lives also damaged Germany’s ability to cultivate food and livestock; running farms was laborintensive, and there were not enough young men left in the country to man its agricultural sector. In 1915, the manufacture of war-related products provided a boost to the German economy, but even that contributed to agriculture’s decline; every worker employed in a factory was one more unable to tend to a farm. The loss of productivity in agriculture is a prime example of the hidden, or indirect, costs of the war. 46 Which, back then, could really buy you something. ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 21 Long-Term Effects of the Great War The end of World War I saw the leaders of France, England, and the United States meet in Versailles, France, and present a list of demands to the defeated Germans. Respectively, these leaders were George Clemenceau, David Lloyd George, and the aforementioned Woodrow Wilson 47. The German representatives vehemently protested the demands, claiming compliance with them would destroy Germany. Clemenceau, George, and Wilson refused to allow the Germans any leeway 48. Germany gave in on June 28, 1919. This agreement came to be known as the Versailles Treaty. The Ratchet Effect Many historians and economists believe World War I The New Deal profoundly and permanently affected the economies of the involved countries. Several have said the war led to a A series of economic laws and measures passed by “ratchet effect”—such that levels of government spending the U.S. government between 1933 and 1936, meant that had risen (“ratcheted up”) during the war never to help the nation recover from the Great Depression. returned to pre-war levels49. In the United States, this sustained elevation of government spending may have paved the way for the New Deal of the 1930s. Other historians are less convinced of the ratchet effect. Stephen Broadberry and Mark Harrison argue that the only aspects of government spending that remained high after the war were involved with paying back debts the government owed. Funds used to pay off loans are designated as debt service payments. Broadberry and Harrison claim that, while government debt service payments rose, the rest of the increase in spending was a simple reflection of the steadily increasing post-war national income. Who Put America in Charge? Whether or not the United States wanted the position, its entry into the war thrust the country into the spotlight.50 The remaining combatants had reached a stalemate, and the United States’ involvement resulted in a decisive advantage for the Allied Powers. Debate it! Resolved: That America should have let European governments take charge after the war, since the conflict primarily involved European nations. The United States had also furnished crucial supplies to the Allies even before declaring war on Germany. This participation, first as a supplier and then as a combatant, led the other Allied Powers to credit the United States with the crucial tipping of the scales that allowed the Allies to win the war. For better or for worse, it inherited a de facto leadership role after the war. What Happens To The Money? The economic effects of the war were far-reaching and profound—and helped set the stage for World War II, an even more destructive conflict which began in September of 1939. The framework for peace established by the Versailles Treaty may have helped pave the way for that Second World War. Noted British economist John Maynard Keynes had a great deal to say about that possibility. 47 The other two guys really wanted to give Wilson the nickname “George,” but he didn’t go for it. They said words to the effect of, “Too bad. Here’s a pen.” 49 Another way to put this is that, like prices, spending is sticky in the upward direction. 50 Sort of like that dream where you have to give a speech, and realize you’ve forgotten your pants. 48 ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 22 Un-Keen Keynes John Maynard Keynes, who lived from 1883 to 1946, witnessed the effects of the Great War firsthand. In 1919, he published The Economic Consequences of the Peace, a book criticizing the Versailles Treaty. Keynes argued that an integrated and unified Europe would be crucial to building national and international stability, and that the terms of the Treaty prevented that outcome. Keynes also believed that the Treaty conflicted with Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, which Wilson had outlined in a speech before the American Congress in November of 1918. The speech outlined fourteen conditions to which the nations that had been involved in the war should adhere: 1. No more secret agreements (only “open covenants openly arrived at”) 2. Free navigation of all seas 3. An end to all economic barriers between countries 4. Fewer armaments in all countries 5. Impartial decisions regarding the fate of the world’s remaining colonies 6. Russia was to be free of the German Army and allowed to chart its own fate. 7. Belgium should be independent, as it was before the war. 8. France should be fully liberated and allowed to recover Alsace-Lorraine from Germany. 9. Italy’s borders should be set encompass all areas occupied by Italians. 10. Self-determination should be allowed for all those living in Austria-Hungary. 11. Self-determination and guarantees of independence should be allowed for the Balkan states. 12. Non-Turks in the old Ottoman Empire should govern themselves; Turks should govern Turks. 13. An independent Poland should be created for the Polish people, with access to the sea. 51 14. A League of Nations should be set up to guarantee the independence of all states. Keynes argued that the Treaty of Versailles conflicted with one of the basic tenets across the Fourteen Points: the right of people to self-determination. The Treaty dictated the creation of countries such as Poland (which split German territory in the process), prevented others from voluntarily combining (such as Germany and Austria), and placed some under control of members of the League of Nations as mandates (including Syria and Lebanon). Keynes also objected to one very general phrase in the Treaty: that the Germans were expected to pay for “all damage done to the civilian population of the Allies and to their property by the aggression of Germany by land, by sea, and from the air.” According to Keynes, this requirement was not specific enough, and could be argued by lawyers ad infinitum; "by land" and "by sea" might be taken to exclude submarine attacks and sea-based bombardments of land. The reparations the Germans were expected to pay totaled $33 billion. Since it was clear Germany would not be able to pay it all at once, the Allies kindly presented it with an installment plan. Germany would pay the money back in increments of: 51 $375 million per year until 1925 $900 million per year after 1925 (consisting solely of interest payments) Polish lands had been divvied up between the German, Austrian, and Russian Empires prior to the war. ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 23 Keynes made his opinion widely known—that $33 billion in Debate it! reparations was too high, not only because it exceeded estimates of the damage done, but also because he saw no way Resolved: That the financial reparations demanded of Germany were justified. for Germany to come up with that much money. He suggested a more appropriate sum would be $10 billion, which would account for damages to all of the Allied nations 52. Keynes went on to say that the amount of reparations demanded, as well as the thought processes that led to this amount, were unwise53. He laid the blame for this alleged error in judgment at the feet of British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and American President Woodrow Wilson. Keynes accused them of concentrating on political and territorial issues, rather than on financial and economic ones, and argued they had set Europe on the road to ruin. Other economists have disagreed with Keynes54, both on his figures and the circumstances behind them. The most salient opinions that Keynes’ detractors offered are as follows: Germany had the money to pay its war debts, but was unwilling to do so. The reparations demanded of Germany were less than those Germany demanded of France in 1871 after the Franco-Prussian War. Since it verges on impossible to prove or disprove such normative economic opinions, debate continues even today about the German war reparations. What you can take to the bank is that Germany made its final reparations payment in October of 201055. Conclusion World War I was far more destructive than any previous war56. Alliances notwithstanding, we can credit (or blame) improved martial technology57. This was the first time battlefields had seen weapons such as machine guns, tanks, warplanes, and weaponized poison gas. It was also the first time soldiers had been involved in trench warfare on such a large scale. At least nine million soldiers died in a few short years. The Great War was waged not only at the front by soldiers in peril, but in banks and factories. In the end, the superior economies of the Allied Powers helped ensure their victory. This was the first war fought by nations engaged in large-scale industrialization, and the success of that industrialization ultimately determined the winner. The Allies could mobilize troops faster, equip them better, and supply them with food and medical care more efficiently than the Central Powers could. There was one exception among the Allied powers: Russia—and that exception was the first country to surrender on either side. President Woodrow Wilson said that he wanted the Great War to be the “war to end war”—but a second even Greater War, involving all the same major players, would wreck the world all over again in less than two decades. Just as in the Great War, the outcome of that much larger, vastly more destructive conflict would hinge in great part on the economic strength and stability of its combatants. 52 Even if true, there was the argument to be made that Germany should pay punitive damages as well—as a form of punishment. They were probably calculated by the same jury that decided the Apple-Samsung trial. 54 Though not to his face, because of that terrifying moustache. 55 And this is why you shouldn’t get into debt—or start a war. 56 It was a war with a bigger special effects budget. 57 As opposed to marital technology—which I suppose could involve getting married by a robot. 53 ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 24 Works Consulted Ayers, Leonard P. The War With Germany: A Statistical Summary (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1919) Bass, Herbert J. America’s Entry Into World War I: Submarines, Sentiment, or Security? (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964) Broadberry, Stephen and Mark Harrison, “The Economics of World War I: An Overview” in The Economics of World War I. Broadberry and Harrison, eds. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005) Broadberry, Stephen and Peter Howlett. “The United Kingdom During World War I: Business as usual?” In The Economics of World War I. Stephen Broadberry and Mark harrison, eds. (Cambridge: Cambridge university Press, 2005) Cunningham, William J. “The Railroads Under Government Operation. I. The Period to the Close of 1918.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 35 (1921) Galassi, Francesco and Mark Harrison, “Italy at War, 1915–1918” in The Economics of World War I. Broadberry and Harrison, eds. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005) Gregory, Paul R. Russian National Income, 1885–1913. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982) Hautcoeur, Pierre-Cyrille. “Was the Great War a Watershed? The Economics of World War I in France.” In The Economics of World War I. Stephen Broadberry and Mark Harrison, eds. (Cambridge: Cambridge university Press, 2005) Higgs, Robert. Crisis and Leviathan. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989). History Learning Site: Wilson’s Fourteen Points. http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/woodrow_wilson1.htm Hurley, Edward N. The Bridge to France. http://www.gwpda.org/wwi-www/Hurley/bridgeTC.htm Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communications from Ancient Times to the Internet. (Scribner, 1996) Maddison, Angus. The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective. OECD, 2001. Peacock, Alan T. and Jack Wiseman. The Growth of Public Expenditure in the United Kingdom (London: Allen and Unwin, 1967). Ritschl, Albrecht. “The Pity of Peace: Germany’s Economy at War, 1914–1918 and beyond.” In The Economics of World War I. Stephen Broadberry and Mark Harrison, eds. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). Rockoff, Hugh. Drastic Measures: A History of Wage and Price Controls in the United States. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004) Rockoff, Hugh. Until It’s Over, Over There: The U.S. Economy in World War I, NBER Working Paper 10580 (2004). Salter, J.A. Allied Shipping Control: An Experiment in International Administration. (Clarendon Press, 1921). Walton, Gary M. and Hugh Rockoff. History of the American Economy. South-Western College Publishers, 2004). ECONOMICS OF WWI RESOURCE | 25 About the Author Dan Jolley has been a writer longer than most of the people reading this guide have been alive—a fact that does not make him feel older than dirt. Like, at all. Really. On the plus side, he was able to write a lot of this guide from personal experience. Anyone wanting to know more about the various novels, comic books, children’s books, and video games Dan has written should visit www.danjolley.com. You’ll discover that he is not currently writing a new comic book in which an Academic Decathlon team steps through a time portal into the trenches of World War I. About the Editor Daniel Berdichevsky goes by many titles: professional nerd, alpaca-in-chief, and “most likely DemiDec team member to kiss a giraffe”.58 Daniel’s Academic Decathlon adventures began shortly after the end of World War I, though they did not become Alpacademic Decathlon adventures until the early 2000s. Shortly thereafter, he learned the sound of a happy alpaca—pwaa—and nothing has been the same since. Daniel edited most of this resource in Perth, which will be hosting the first-ever Australian59 round of the World Scholar’s Cup in 2014.60 You can reach Daniel at dan@demidec.com or follow him on Facebook at www.facebook.com/dan.berd. 58 You’ll note that he also favors British punctuation. Pwaa-stralian. 60 Kangaroos and alpacas can peaceably coexist. 59