Unit 6 – Reconstruction 1865 - 1877

advertisement

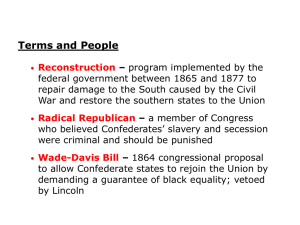

Unit 6 – Reconstruction 1865 - 1877 Section 1 - Reconstruction Begins While Southerners were mourning the loss of their financially lucrative labor source, more than four million former slaves were trying to find their way as freedmen. The majority of the emancipated blacks were illiterate, with limited skills and financial resources. The one factor that connected most former slaves was a thirst for religion. Many masters had allowed their slaves to worship beside them, but with the Emancipation Proclamation former slaves began developing their own churches. Between 1850 and 1870, the black Baptist Church had grown by 350,000 members, and the African Methodist Episcopal Church quadrupled its membership. Many blacks were driven toward literacy largely out of their desire to read the Bible. In response to the desire for literacy, black schools were established—some with black teachers and others with white teachers, primarily female missionaries from the American Missionary Association. It was not uncommon to see grandmothers attend school alongside their grandchildren. However, there were not enough teachers to meet the demands, and eventually the federal government stepped in to help. At President Lincoln’s encouragement, along with pressure from influential Northern abolitionists, Congress developed the Freedmen’s Bureau on March 8, 1865. This early social welfare program was dedicated to educating, training, and providing financial and moral support for former slaves. One strong supporter of the Bureau was Union general Oliver O. Howard, the eventual founder and president of Howard University in Washington, D.C. With Howard’s support, over 200,000 blacks learned to read through the programs offered by the Freedmen’s Bureau. Unfortunately, the system became corrupt and it was never able to achieve its potential. The catch-phrase of the day was “40 acres and a mule,” as that was what was promised to the emancipated slaves, with the plan to settle them on land confiscated from the Confederates. However, corrupt officials usually kept the land for themselves and manipulated many former slaves into signing labor contracts that essentially placed them back in a slave-like environment. White Southerners campaigned against the Freedmen’s Bureau. Many felt that although they had lost the right to own slaves, they still possessed racial superiority. The Freedmen’s Bureau threatened that presumption. When President Lincoln was assassinated in April of 1865, and Andrew Johnson stepped into office, the Freedman’s Bureau lost an ally in the White House. Johnson, a Southerner, had been raised with the same racial biases as those who opposed the Freedmen’s Bureau, and he allowed the program to expire in 1872. Despite its flaws, the Freedmen’s Bureau had helped a majority of former slaves achieve some degree of success. Freed slaves began to develop a political unity and refused to be discouraged. Their primary political vehicle was the northern-based Union League, which educated freedmen on civil responsibility and campaigned for Republican leaders who supported the freedmen’s cause. Blacks themselves also began to assume political roles. Sixteen black men served in the Senate and the House of Representatives between 1868 and 1876, and numerous others took on roles in state and local government. This was much to the dismay of their former masters, who scorned the white allies of these black political leaders. The whites who allied themselves with blacks became known as either “scalawags” or “carpetbaggers.” Scalawags were Southerners who opposed secession and were accused of harming the South by helping the blacks and stealing from their state treasuries. Carpetbaggers were Northerners who were accused of putting all their worldly belongings into a carpetbag suitcase and coming to the south at war’s end to gain personal profit and power. The name-calling on occasion erupted into violence, suggesting that Southerners believed that they were superior not only to blacks, but to black-friendly whites, as well. This disharmony was typical of the early stages of Reconstruction. Presidential Reconstruction In the spring of 1865, the Civil War came to an end, leaving over 620,000 dead and a devastating path of destruction throughout the south. The North now faced the task of reconstructing the ravaged and indignant Confederate states. There were many important questions that needed to be answered as the nation faced the challenges of peace: Who would direct the process of Reconstruction? The South itself, Congress, or the President? Should the Confederate leaders be tried for treason? How would the south, both physically and economically devastated, be rebuilt? And at whose expense? How would the south be readmitted and reintegrated into the Union? What should be done with over four million freed slaves? Were they to be given land, social equality, education, and voting rights? On April 11, 1865, two days after Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender, President Abraham Lincoln delivered his last public address, during which he described a generous Reconstruction policy and urged compassion and openmindedness throughout the process. He pronounced that the Confederate states had never left the Union, which was in direct opposition to the views of Radical Republican Congressmen who felt the Confederate states had seceded from the Union and should be treated like “conquered provinces.” On April 14, Lincoln held a Cabinet meeting to discuss post-war rebuilding in detail. President Lincoln wanted to get southern state governments in operation before Congress met in December in order to avoid the persecution of the vindictive Radical Republicans. That same night, while Lincoln was watching a play at Ford’s Theatre, a fanatical Southern actor, John Wilkes Booth, crept up behind Lincoln and shot him in the head. Lincoln died the following day, leaving the South with little hope for a nonvindictive Reconstruction. The absence of any provisions in the Constitution that could be applied to Reconstruction led to a disagreement over who held the authority to direct Reconstruction and how it would take place. Lincoln felt the president had authority based on the constitutional obligation of the federal government to guarantee each state a republican government. Even before the war had ended, Lincoln issued the Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction in 1863, his compassionate policy for dealing with the South. The Proclamation stated that all Southerners could be pardoned and reinstated as U.S. citizens if they took an oath of allegiance to the Constitution and the Union and pledged to abide by emancipation. High Confederate officials, Army and Navy officers, and U.S. judges and congressmen who left their posts to aid the southern rebellion were excluded from this pardon. Lincoln’s Proclamation was called the “10 percent plan”: Once 10 percent of the voting population in any state had taken the oath, a state government could be put in place and the state could be reintegrated into the Union. Two congressional factions formed over the subject of Reconstruction. A majority group of moderate Republicans in Congress supported Lincoln’s position that the Confederate states should be reintegrated as quickly as possible. A minority group of Radical Republicans--led by Thaddeus Stevens in the House and Ben Wade and Charles Sumner in the Senate--sharply rejected Lincoln’s plan, claiming it would result in restoration of the southern aristocracy and re-enslavement of blacks. They wanted to effect sweeping changes in the south and grant the freed slaves full citizenship before the states were restored. The influential group of Radicals also felt that Congress, not the president, should direct Reconstruction. In July 1864, the Radical Republicans passed the Wade-Davis Bill in response to Lincoln’s 10 percent plan. This bill required that more than 50 percent of white males take an “ironclad” oath of allegiance before the state could call a constitutional convention. The bill also required that the state constitutional conventions abolish slavery. Confederate officials or anyone who had “voluntarily borne arms against the United States” were banned from serving at the conventions. Lincoln pocket-vetoed, or refused to sign, the proposal, keeping the Wade-Davis bill from becoming law. This is where the issue of Reconstruction stood on the night of Lincoln’s assassination, when Andrew Johnson became president. In the 1864 election, Lincoln chose Andrew Johnson as his vice presidential running mate as a gesture of unity. Johnson was a War Democrat from Tennessee, a state on the border of the north-south division in the United States. Johnson was a good political choice as a running mate because he helped garner votes from the War Democrats and other pro-Southern groups. Johnson was born to impoverished parents in North Carolina, orphaned at an early age, and moved to Tennessee. Self-educated, he rose through the political ranks to be a congressman, a governor of Tennessee, and a United States senator. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Johnson was the only senator from a seceding state who remained loyal to the Union. Johnson's political career was built on his defense of small farmers and poor white southerners against the aristocratic classes. He was heard saying during the war, “Damn the Negroes, I am fighting those traitorous aristocrats, their masters.” Unfortunately, Johnson was unprepared for the presidency thrust upon him with Lincoln’s assassination. The Radical Republicans believed at first that Johnson, unlike Lincoln, wanted to punish the South for seceding. However, on May 29, 1865, Johnson issued his own reconstruction proclamation that was largely in agreement with Lincoln’s plan. Johnson, like Lincoln, held that the southern states had never legally left the Union, and he retained most of Lincoln’s 10 percent plan. Johnson’s plan went further than Lincoln’s and excluded those Confederates who owned taxable property in excess of $20,000 from the pardon. These wealthy Southerners were the ones Johnson believed led the South into secession. However, these Confederates were allowed to petition him for personal pardons. Before the year was over, Johnson, who seemed to savor power over the aristocrats who begged for his favor, had issued some 13,000 such pardons. These pardons allowed many of the planter aristocrats the power to exercise control over Reconstruction of their states. The Radical Republicans were outraged that the planter elite once again controlled many areas of the south. Johnson also called for special state conventions to repeal the ordinances of secession, abolish slavery, repudiate all debts incurred to aid the Confederacy, and ratify the Thirteenth Amendment. Suggestions of black suffrage were scarcely raised at these state conventions and promptly quashed when they were. By the time Congress convened in December 1865, the southern state conventions for the most part had met Johnson’s requirements. On December 6, 1865, Johnson announced that the southern states had met his conditions for Reconstruction and that in his opinion the Union was now restored. As it became clear that the design of the new southern state governments was remarkably like the old governments, both moderate Republicans and the Radical Republicans grew increasingly angry. Section 2 - Congressional Reconstruction The Black Codes When Congress convened in December 1865, the legislative members from the newly reconstituted southern states presented themselves at the Capitol. Among them were Alexander H. Stephens--who was the ex-vice-president of the Confederacy--four Confederate generals, five colonels, and several other rebels. After four bloody years of war, the presence of these Confederates infuriated the Congressional Republicans, who immediately denied seats to all members from the eleven former Confederate states. Adding to the controversy, the new southern legislatures began passing repressive “Black Codes.” Mississippi passed the first of these laws designed to restrict the freedom of the emancipated blacks in November 1865. The South intended to preserve slavery as nearly as possible in order to guarantee a stable labor supply. While life under the Black Codes was an improvement over slavery, the codes identified blacks as a separate class with fewer liberties and more restrictions than white citizens. The details of the Codes varied from state to state, but some universal policies applied. Existing black marriages were recognized, blacks could testify in court cases involving other blacks, and blacks could own certain kinds of property. In contrast, blacks could not serve on a jury and were not allowed to vote. They were barred from renting and leasing land and in many states could not carry firearms without a license. The Codes also had strict labor provisions. Blacks were required to enter into annual labor contracts and could be punished, required to forfeit back pay, or forced to work by paid “Negro catchers” if they violated the contract. Vagrants, drunkards, and beggars were given stiff fines, and if they could not pay them, they were sentenced to work on a chain gang. Most former slaves lacked capital and marketable skills and had only manual labor as a means of support. The black activist Frederick Douglass explained: "A former slave was free from the individual master, but the slave of society. He had neither money, property, nor friends. He was free from the old plantation, but he had nothing but the dusty road under his feet." Thousands of freedmen became sharecropper farmers, which led them to becoming indentured servants, indebted to the plantation owner and resulting in generations of people working the same plot of land. The situation in the south left Northerners wondering what they had gone to war for, since blacks were essentially being re-enslaved. Even moderate Republicans started to adopt the views of the more radical party members. Johnson’s lenient Reconstruction plan, along with the South’s aggressive tactics, led Congress to reject Johnsonian Reconstruction and create the Joint Committee on Reconstruction. Congress Takes Control A clash between President Johnson and Congress over Reconstruction was now inevitable. By the end of 1865, Radical Republican views had gained a majority in Congress, and the decisive year of 1866 saw a gradual diminishing of President Johnson’s power. In June of 1866, the Joint Committee on Reconstruction determined that, by seceding, the southern states had forfeited “all civil and political rights under the Constitution.” The Committee rejected President Johnson’s Reconstruction plan, denied seating of southern legislators, and maintained that only Congress could determine if, when, and how Reconstruction would take place. Part of the Reconstruction plan devised by the Joint Committee to replace Johnson’s Reconstruction proclamation is demonstrated in the Fourteenth Amendment. Northern Republicans did not want to give up the political advantage they held, especially by allowing former Confederate leaders to reclaim their seats in Congress. Since the South did not participate in Congress from 1861 to 1865, Republicans were able to pass legislation that favored the North, such as the Morrill Tariff, the Pacific Railroad Act, and the Homestead Act. Republicans were also concerned that the South’s congressional representation would increase since slaves were no longer considered only three-fifths of a person. This population increase would tip the congressional leadership to the South, enabling them to perpetuate the Black Codes and virtually re-enslave blacks. The strained relations between Congress and the president became increasingly apparent in February 1866 when President Johnson vetoed a bill to extend the life of the Freedmen’s Bureau. The Freedmen’s Bureau had been established in 1865 to care for refugees, and now Congress wanted to amend it to include protection for the black population. Although the bill had broad support, President Johnson claimed that it was an unconstitutional extension of military authority since wartime conditions no longer existed. Congress did override Johnson’s veto of the Freedmen’s Bureau, helping it last until the early 1870s. Striking back, Congress passed the Civil Rights Bill in March 1866. This Bill granted American citizenship to blacks and denied the states the power to restrict their rights to hold property, testify in court, and make contracts for their labor. Congress aimed to destroy the Black Codes and justified the legislation as implementing freedom under the Thirteenth Amendment. Johnson vetoed the Civil Rights Bill, which prompted most Republicans to believe there was no chance of future cooperation with him. On April 9, 1866, Congress overrode the presidential veto, and from that point forward, Congress frequently overturned Johnson’s vetoes. The Republicans wanted to ensure the principles of the Civil Rights Act by adding a new amendment to the Constitution. Doing so would keep the Southerners from repealing the laws if they ever won control of Congress. In June 1866, Congress sent the proposed Fourteenth Amendment, which in the context of the times was a radical measure, to the states for ratification: It acknowledged state and federal citizenship for persons born or naturalized in the United States. It forbade any state to diminish the “privileges and immunities” of citizenship, which was the section that struck at the Black Codes. It prohibited any state to deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without “due process of law.” It forbade any state to deny any person “the equal protection of the laws.” It disqualified former Confederates from holding federal and state office. It reduced the representation of a state in Congress and the Electoral College if it denied blacks voting rights. It guaranteed the federal debt, while rejecting all Confederate debts. All Republicans agreed that no state would be welcomed back to the Union without ratifying the Fourteenth Amendment. In contrast, President Johnson recommended that the states reject it. Johnson’s home state of Tennessee was the first to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, while the other 10 seceded states rejected it. During this same time, bloody race riots erupted in several southern cities, adding fuel to the Reconstruction battle. Radical Republicans blamed the indiscriminate massacre of blacks on Johnson’s policies. The congressional election of 1866 widened the divide between President Johnson and Congress. President Johnson embarked on a “swing around the circle” tour where he gave speeches at various Midwestern cities to rally the public around his policy of lenient Union recognition for the southern states. His tour was a complete failure as he exchanged hot-tempered insults with the critics in the crowd. To counter Johnson’s rhetoric, Congressional Republicans took to “waving the bloody shirt”--appealing to voters by reminding them of the sacrifices the Union made during the Civil War. When the congressional election was complete, the Republicans won more than the two-thirds majority in the House and the Senate that they needed to override any presidential vetoes. If the southern states had been willing to adopt the Fourteenth Amendment, coercive measures might have been avoided. On March 2, 1867, Congress passed the Military Reconstruction Act, which became the final plan for Reconstruction and identified the new conditions under which the southern governments would be formed. Tennessee was exempt from the Act because it had ratified the Fourteenth Amendment. This legislation divided the former Confederacy into five military districts, each occupied by a Union general and his troops, whom Southerners contemptuously called “bluebellies.” The officers had the power to maintain order and protect the civil rights of all persons. The southern states were required to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment and adopt new state constitutions guaranteeing blacks the right to vote in order for their representatives to be admitted to Congress and military rule to end (which paved the way for easy ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment later). However, the Act did not go as far as giving freedmen land or education at federal expense. Although peacetime military rule seemed contrary to the spirit of the Constitution, the Supreme Court allowed it. The hated “bluebellies” remained until the new Republican regimes were firmly established in each state. It was not until 1877 that the last federal troops left the south. Radical Republicans were still concerned that once the states were re-admitted to the Union, they would amend their constitutions and withdraw black suffrage. They moved to safeguard their legislation by adding it to the federal Constitution with the Fifteenth Amendment. The amendment prohibited the states from denying anyone the right to vote “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” In 1870, the required number of states had ratified the amendment, and it became part of the Constitution. The Fifteenth Amendment did not guarantee the right to vote regardless of sex, which outraged feminists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Equally disappointing to feminists was the fact that the Fourteenth Amendment marked the first appearance of the word “male” in the Constitution. Efforts to include female suffrage in the Fifteenth Amendment were defeated, and 50 years passed before an amendment to the Constitution granted women the right to vote. While most of the southern states had quickly ratified the Fifteenth Amendment under pressure from the federal government, Democratic Party dominance in those states assured the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments were largely ignored. Literacy tests and poll taxes were often used to keep blacks from voting. Intimidation and lynching were also common means to keep blacks from the polls. Full suffrage for blacks was not realized until 1965. The Civil Rights Act of 1875 was the last congressional Reconstruction measure. It prohibited racial discrimination in jury selection, transportation, restaurants, and "inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement." It did not guarantee equality in schools, churches, and cemeteries. Unfortunately, the Act lacked a strong enforcement mechanism, and dismayed Northerners did not attempt another civil rights act for 90 years. Section 3 - The End of Reconstruction Impeachment of Johnson In 1867, the political battle between President Johnson and Congress over southern Reconstruction came to a confrontation. The Radical Republicans in Congress were not content with curbing Johnson’s authority by overriding his vetoes--they wanted to remove him altogether. Under the laws of the time, removing Johnson meant that Ben Wade, the president pro tempore of the Senate, would become president. While many considered Johnson to be an inadequate president, he had done nothing to merit removal from office. Johnson believed that everything he did was in the interest of preserving a constitutional government. When Congress passed laws retracting powers granted to the president by the Constitution, Johnson refused to accept them. For example, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act in 1867, which prohibited the president from removing senate-approved officials without first gaining the consent of the Senate. The Senate’s goal was to keep Johnson from firing Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who had been appointed by President Lincoln. Stanton was a staunch supporter of the Congress and did not agree with President Johnson’s Reconstruction policies. Johnson believed the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional and challenged it head-on by dismissing Stanton in early 1868. In response, the House voted 126 to 47 to impeach Johnson for "high crimes and misdemeanors,” and they started the procedures set up in the Constitution for removing the president. They charged him with eleven articles of impeachment, eight of which focused on the unlawful removal of Stanton. Johnson faced a Senate tribunal, presided over by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase. Johnson’s lawyers set out to prove that the Tenure of Office Act did not protect Stanton because it gave Cabinet members tenure “during the term of the President by whom they may have been appointed,” and it was President Lincoln who had appointed Stanton. On May 16, 1868, the Senate voted and the Radical Republicans were a mere one vote short of the two-thirds majority needed to remove Johnson from office. If Johnson had been forced from office on such weak charges, it may have set a destructive precedent and permanently undermined the executive branch of the United States government. To appease the Radical Republicans, Johnson agreed to stop obstructing the process of Reconstruction. He named a Secretary of War who was committed to enforcing the new laws, and Reconstruction began in earnest. Ironically, in 1926 the Supreme Court found the Tenure of Office Act to be unconstitutional. The Reconstructed South The postwar South, where most of the fighting had occurred, faced many challenges. In the war’s aftermath, Southerners experienced collapsed property values, damaged railroads, and agricultural hardships. The elite planters were faced with overwhelming economic adversity perpetuated by a lack of laborers for their fields. However, it was the newly freed slaves in the former Confederate states that faced the greatest challenge: what to do with their newfound freedom. Blacks acquired new rights and opportunities, such as equality before the law and the rights to own property, be married, attend schools, enter professions, and learn to read and write. One of the first opportunities the former slaves took advantage of was the chance to educate themselves and their children. The new Radical Republican state governments took steps to provide adequate public schools for the first time in the south. Nearly 600,000 black students, from children to the elderly, were in southern schools by 1877. Although State Reconstruction officials tried to prohibit discrimination, the new schools practiced racial segregation, and the black schools generally received less funding than white schools. Black churches, recognizing the importance of the education initiatives, helped raise money to build schools and pay teachers, and many northern missionaries moved south to serve as teachers. Another opportunity the former slaves pursued was involvement in politics. When the Fifteenth Amendment offered the chance for suffrage, black men seized the opportunity and began to organize politically. The freedmen affiliated themselves with the Republican Party, and hundreds of black delegates participated in statewide political conventions. Blacks used the Union Leagues to organize into a network of political clubs, provide political education, and campaign for Republican candidates. Black women did not have the right to vote at the time, but they aided the political movement with rallies and meetings that supported the Republican candidates. In the new state governments of the south, black participation was a novelty. As their political involvement grew, several freedmen were elected to office. Those who were elected generally had some education, had served in the Union Army during the Civil War, had been free before the 1860s, or had some prior experience in public service. Nearly 600 blacks served as state legislators, and many participated in the local governments as mayors, judges, and sheriffs. Between 1868 and 1876 at the federal level, 14 black men served in the House of Representatives and two black men served in the Senate--Hiram Revels and Blanche K. Bruce, both born in Mississippi and educated in the north. The freedmen’s involvement in politics caused a great deal of controversy in the south, where the idea of former slaves holding office was not widely supported. While several black men held political offices, the top positions with the most power in southern state governments were held by the freedmen’s white Republican allies. The Confederate-minded whites soon came to call them “carpetbaggers” and “scalawags,” depending on their place of birth. The Confederates described “carpetbaggers” as Northerners who packed all their belongings in carpetbag suitcases and rushed south in hopes of finding economic opportunity and personal power, which was true in some instances. Many of these Northerners were actually businessmen, professionals, teachers, and preachers who either wanted to “modernize” the south or were driven by a missionary impulse. The “scalawags” were native Southerners and Unionists who had opposed secession. The former Confederates accused them of cooperating with the Republicans because they wanted to advance their personal interests. Many of the “scalawags” became Republicans because they had originally supported the Whig Party before secession and they saw the Republicans as the logical successors to the defunct Whig Party. Some Southern whites resorted to savage tactics against the new freedom and political influence blacks held. Several secret vigilante organizations developed. The most prominent terrorist group was the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), first organized in Pulaski, Tennessee in 1866. Members of the KKK, called “Klansmen,” rode around the south, hiding under white masks and robes, terrorizing Republicans and intimidating black voters. They went so far as to flog, mutilate, and even lynch blacks. Congress, outraged by the brutality of the vigilantes and the lack of local efforts to protect blacks and persecute their tormentors, struck back with three Enforcement Acts (1870-1871) designed to stop the terrorism and protect black voters. The Acts allowed the federal government to intervene when state authorities failed to protect citizens from the vigilantes. Aided by the military, the program of federal enforcement eventually undercut the power of the Ku Klux Klan. However, the Klan’s actions had already weakened black and Republican morale throughout the south. As the Radical Republican influence diminished in the south, other interests occupied the attention of Northerners. Western expansion, Indian wars, corruption at all levels of government, and the growth of industry all diverted attention from the civil rights and well-being of ex-slaves. By 1876, Radical Republican regimes had collapsed in all but two of the former Confederate states, with the Democratic Party taking over. Despite the Republicans’ efforts, the planter elite were regaining control of the south. This group came to be known as the “Redeemers,” a coalition of prewar Democrats and Union Whigs who sought to undo the changes brought about in the south by the Civil War. Many were ex-plantation owners called “Bourbons” whose policies affected blacks and poor whites, leading to an increase in class division and racial violence in the post-war south. Reconstruction Ends In the election of 1868, General Ulysses S. Grant, the most popular northern hero to emerge from the Civil War, became president. Grant ran on the Republican ticket with the slogan, “Let us have peace” against the Democratic candidate Horatio Seymour. The Republican platform endorsed the Reconstruction policy of Congress, payment of the national debt with gold, and cautious defense of black suffrage. Grant swept the Electoral College with 214 votes, compared to Seymour’s 80. However, Grant only had about 300,000 more popular votes than Seymour, with the more than 500,000 black voters accounting for his margin of victory. Unfortunately, the qualities that had made Grant a fine military leader did not serve him well as president. Grant had a dislike of politics and passively followed the lead of Congress in the formulation of policy. He was honest to the point of being the victim of unscrupulous friends and schemers. All of this left him ineffective and caused others to question his leadership abilities. One scandal that rocked the Grant administration was the Crédit Mobilier scandal. It came to light during the 1872 election that the Union Pacific Railroad had formed the Crédit Mobilier construction company and then hired themselves at inflated prices to build the railroad line. The company then “bought” several prominent Republican congressmen with shares of its valuable stock. A congressional investigation led to the formal censure of only two of the corrupt congressmen. The Whiskey Ring affair was also revealed during the 1872 election. The Whiskey Ring bribed tax collectors to rob the Treasury of millions in excise-tax revenues. Grant was adamant that no guilty man involved in the scheme should escape prosecution, but when he discovered his private secretary was involved, he helped exonerate him. Grant’s Secretary of War was also discovered to be involved in accepting bribes from suppliers to the Indian reservations. The scandals and incompetence surrounding Grant’s administration, along with disagreement among party members, led a group of Republicans to break off and start the reform-minded Liberal Republican Party. Unlike the other Republicans, the Liberal Republicans favored gold to redeem greenbacks, low tariffs, an end to military Reconstruction, and restoration of the rights of former Confederates. The Liberal Republicans were generally well educated and socially prominent, and most had initially supported Reconstruction. They nominated Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune, for president in 1872. The Democrats also endorsed Greeley’s candidacy, even though he had always been hostile toward them. Grant, as expected, won the Republican Party’s nomination for a second term. In 1872, voters had to choose between two presidential candidates who were not politicians and who had questionable qualifications. In the end, the regular Republicans were able to sway votes by once again “waving the bloody shirt”-appealing to the hatred of northern voters and reminding them of the trials of war. Grant won with a popular majority of nearly 800,000 votes and with 286 Electoral College votes to Greeley’s 66. After Grant’s victory, the Republicans did clean house with some civil-service reform and reduction of high Civil War tariffs. An economic crisis in America followed shortly after the presidential election of 1872. Unbridled expansion of factories, railroads, and farms and contraction of the money supply through the withdrawal of greenbacks helped trigger the Panic of 1873. This was the longest and most severe depression the country had experienced, with over 15,000 businesses filing bankruptcy, widespread unemployment, and a slowdown in railroad and factory building. The split of the Republican Party helped the Democrats gain seats in the Senate and carry the House of Representatives in the 1874 congressional elections. With control of the House, the Democrats immediately launched more investigations into the presidential scandals and discovered further evidence of corruption. Although President Grant’s terms in office were tainted with corruption, his supporters urged him to run for a third term in 1876. Some believe he did not run due to the many scandals that emerged during his terms. Others believe it was because the House passed a resolution to limit presidents to two terms in office. Either way, Grant was out of the running, and the Republicans turned to a compromise candidate: Rutherford B. Hayes from Ohio. Hayes was a three-time governor of Ohio, and his chief virtue was that no one knew much about him, so both Radicals and reformers accepted him. The Democratic Party nominated Samuel J. Tilden, a famous lawyer from New York who had overthrown the notorious Boss Tweed. Both Hayes and Tilden favored conservative rule in the south and civil service reform. Since the campaign did not generate any substantive issues, the two parties turned to mud-slinging, with Republicans claiming Democrats were Confederates and Democrats pointing to the corruption of the past Republican presidency. On Election Day, Tilden garnered 184 electoral votes--only one short of the majority needed--and nearly 300,000 more popular votes than Hayes. However, there were 20 disputed electoral votes due to irregular returns from Oregon, Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina. In the three disputed southern states, rival canvassing boards submitted different returns to Congress: one supporting a Democratic win and the other supporting a Republican win. Unfortunately, the Constitution had no provisions outlined for such a situation, so in January 1877, Congress set up a special electoral commission consisting of 15 men from the Senate, House, and Supreme Court. The electoral commission reviewed the votes for Oregon, Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina and, by partisan result of eight Republicans to seven Democrats, gave the Republicans the electoral votes. The House voted to accept the commission’s decision, declaring Hayes President by an electoral vote of 185 to 184. Congressional Democrats threatened to filibuster and prevent the recording of the electoral vote. Many southern Democrats began to make informal agreements with the Republicans behind closed doors. In the Compromise of 1877, Republican Congressman James Garfield met with powerful southern Democrats at the Wormley Hotel in Washington. The Republicans promised that if Hayes was elected he would withdraw the last of the federal troops from the south, allowing the only remaining Republican Reconstruction governments to collapse. Another concession the Republicans made was to promise support for a bill that would subsidize construction of the southern transcontinental railroad line. Finally, the Republicans also consented to giving the position of Postmaster-General to a southern white. The Compromise came at a price: It gave the Democrats justification to desert Tilden, since it would allow them to regain political rule in the south. With the compromise, the Republicans had quietly given up their fight for racial equality and blacks’ rights in the south. In 1877, Hayes withdrew the last federal troops from the south, and the bayonet-backed Republican governments collapsed, thereby ending Reconstruction. Over the next three decades, the civil rights that blacks had been promised during Reconstruction crumbled under white rule in the south. The plight of southern Blacks was forgotten in the north as they were segregated and condemned to live in poverty with little hope. Radical Reconstruction had never offered more than an uncertain commitment to equality, but it had left an enduring legacy with the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments waiting to be enforced.