Vertical Versus Shared Leadership as Predictors of the

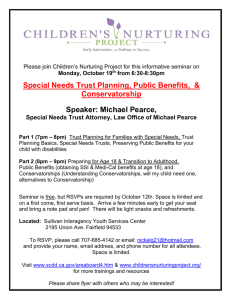

advertisement