Research on Internet Recruiting and Testing:

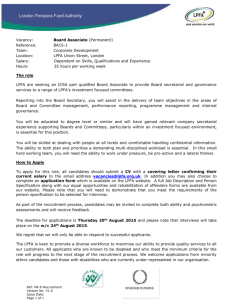

advertisement