The Communications Adjunct Model: An Innovative Approach to

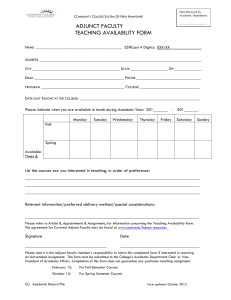

advertisement