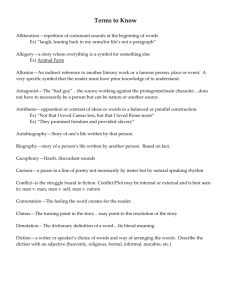

Basics of English Studies: An introductory course for students of

advertisement