Gregor Mendel - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

advertisement

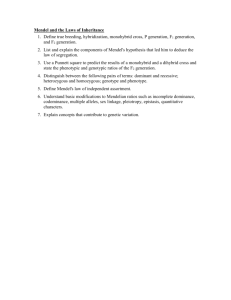

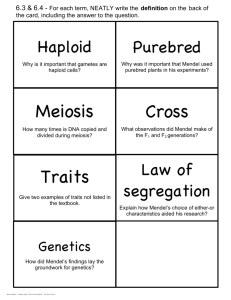

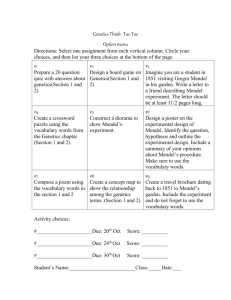

Gregor Mendel - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 8/1/10 11:30 AM Gregor Mendel From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Gregor Johann Mendel (July 20, 1822[1] – January 6, 1884) was an Augustinian priest and scientist, who gained posthumous fame as the figurehead of the new science of genetics for his study of the inheritance of certain traits in pea plants. Mendel showed that the inheritance of these traits follows particular laws, which were later named after him. The significance of Mendel's work was not recognized until the turn of the 20th century. The independent rediscovery of these laws formed the foundation of the modern science of genetics. [2] Gregor Johann Mendel Born July 20, 1822 Heinzendorf bei Odrau, Silesia, Austrian Empire Died January 6, 1884 (aged 61) Brno, Austria-Hungary Contents 1 Biography 1.1 Experiments on plant hybridization 1.2 Life after the pea experiments 2 Rediscovery of Mendel's work 3 Gallery 4 See also 5 References 6 Bibliography 7 External links Nationality Austria-Hungary Fields Genetics Institutions Abbey of St. Thomas in Brno Alma University of Vienna mater Known for Discovering genetics Biography Mendel was born into an ethnic German family in Heinzendorf bei Odrau, Austrian Silesia, Austrian Empire (now Hynčice, Czech Republic), and was baptized two days later. He was the son of Anton and Rosine Mendel, and had one older sister and one younger. They lived and worked on a farm which had been owned by the Mendel family for at least 130 years.[3] During his childhood, Mendel worked as a gardener, studied beekeeping, and as a young man attended the Philosophical Institute in Olomouc in 1840–1843. Upon recommendation of his physics teacher Friedrich Franz, he entered the Augustinian Abbey of St Thomas in Brno in 1843. Born Johann Mendel, he took the name Gregor upon entering monastic life. In 1851 he was sent to the University of Vienna to study under the sponsorship of Abbot C. F. Napp. At Vienna, his professor of physics was Christian Doppler.[4] Mendel returned to his abbey in 1853 as a teacher, principally of physics, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregor_Mendel Page 1 of 6 Gregor Mendel - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 8/1/10 11:30 AM and by 1867, he had replaced Napp as abbot of the monastery.[5] Besides his work on plant breeding while at St Thomas's Abbey, Mendel also bred bees in a bee house that was built for him, using bee hives that he designed.[6] He also studied astronomy and meteorology[5] , founding the 'Austrian Meteorological Society' in 1865.[4] The majority of his published works were related to meteorology.[4] Experiments on plant hybridization Gregor Mendel, who is known as the "father of modern genetics", was inspired by both his professors at university and his colleagues at the monastery to study variation in plants, and he conducted his study in the monastery's two hectare [7] experimental garden, which was originally planted by the abbot Napp in 1830.[5] Between 1856 and 1863 Mendel cultivated and tested some 29,000 pea plants (i.e., Pisum sativum). This study showed that one in four pea plants had purebred recessive alleles, two out of four were hybrid and one out of four were purebred dominant. His experiments led him to make two generalizations, the Law of Segregation and the Law of Independent Assortment, which later became known as Mendel's Laws of Inheritance. Mendel did read his paper, Experiments on Plant Hybridization, at two meetings of the Natural History Society of Brünn in Moravia in 1865. When Mendel's paper was published in 1866 in Proceedings of the Natural History Society of Brünn,[8] it had little impact and was cited about three times over the next thirty-five years. (Notably, Charles Darwin was unaware of Mendel's paper, according to Jacob Bronowski's The Ascent of Man.) His paper was criticized at the time, but is now considered a seminal work. Life after the pea experiments After Mendel completed his work with peas, he turned to experimenting with honeybees, in order to extend his work to animals. He produced a hybrid strain (so vicious they were destroyed), but failed to generate a clear picture of their heredity because of the difficulties in controlling mating behaviours of queen bees. He also described novel plant species, and these are denoted with the botanical author abbreviation "Mendel". After he was elevated as abbot in 1868, his scientific work largely ended as Mendel became consumed with his increased administrative responsibilities, especially a dispute with the civil government over their attempt to impose special taxes on religious institutions. [9] At first Mendel's work was rejected, and it was not widely accepted until after he died. At that time most biologists held the idea of blending inheritance, and Charles Darwin's efforts to explain inheritance through a theory of pangenesis were unsuccessful. Mendel's ideas were rediscovered in the early twentieth century, and in the 1930s and 1940s the modern synthesis combined Mendelian genetics with Darwin's theory of natural selection. Mendel died on January 6, 1884, at age 61, in Brno, Moravia, Austria-Hungary (now Czech Republic), from chronic nephritis. Czech composer Leoš Janáček played the organ at his funeral. After his death the succeeding abbot burned all papers in Mendel's collection, to mark an end to the disputes over taxation.[10] Rediscovery of Mendel's work http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregor_Mendel Page 2 of 6 Gregor Mendel - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 8/1/10 11:30 AM It was not until the early 20th century that the importance of his ideas was realized. By 1900, research aimed at finding a successful theory of discontinuous inheritance rather than blending inheritance led to independent duplication of his work by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and the rediscovery of Mendel's writings and laws. Both acknowledged Mendel's priority, and it is thought probable that de Vries did not understand the results he had found until after reading Mendel.[2] Though Erich von Tschermak was originally also credited with rediscovery, this is no longer accepted because he did not understand Mendel's laws. [11] Though de Vries later lost interest in Mendelism, other biologists started to establish genetics as a science. [2] Mendel's results were quickly replicated, and genetic linkage quickly worked out. Biologists flocked to the theory, even though it was not yet applicable to many phenomena, it sought to give a genotypic Dominant and recessive phenotypes. understanding of heredity which they felt was lacking in previous (1) Parental generation. (2) F1 studies of heredity which focused on phenotypic approaches. Most generation. (3) F2 generation. prominent of these latter approaches was the biometric school of Karl Pearson and W.F.R. Weldon, which was based heavily on statistical studies of phenotype variation. The strongest opposition to this school came from William Bateson, who perhaps did the most in the early days of publicising the benefits of Mendel's theory (the word "genetics", and much of the discipline's other terminology, originated with Bateson). This debate between the biometricians and the Mendelians was extremely vigorous in the first two decades of the twentieth century, with the biometricians claiming statistical and mathematical rigor, whereas the Mendelians claimed a better understanding of biology. In the end, the two approaches were combined as the modern synthesis of evolutionary biology, especially by work conducted by R. A. Fisher as early as 1918. Mendel's experimental results have later been the object of considerable dispute. [10] Fisher analyzed the results of the F2 (second filial) ratio and found them to be implausibly close to the exact ratio of 3 to 1.[12] Only a few would accuse Mendel of scientific malpractice or call it a scientific fraud—reproduction of his experiments has demonstrated the validity of his hypothesis—however, the results have continued to be a mystery for many, though it is often cited as an example of confirmation bias. This might arise if he detected an approximate 3 to 1 ratio early in his experiments with a small sample size, and continued collecting more data until the results conformed more nearly to an exact ratio. It is sometimes suggested that he may have censored his results, and that his seven traits each occur on a separate chromosome pair, an extremely unlikely occurrence if they were chosen at random. In fact, the genes Mendel studied occurred in only four linkage groups, and only one gene pair (out of 21 possible) is close enough to show deviation from independent assortment; this is not a pair that Mendel studied. Some recent researchers have suggested that Fisher's criticisms of Mendel's work may have been exaggerated. [13][14] Gallery http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregor_Mendel Page 3 of 6 Gregor Mendel - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 8/1/10 11:30 AM Bust of Mendel at Gregor Mendel, Gregor Johann Mendel Mendel University of frontispiece from The Augustinian Abbey – memorial plaque in Agriculture and "Mendel's principles of of St Thomas, Brno Olomouc Forestry Brno, Czech heredity: A Defence" Republic See also List of Austrian scientists Mendelian inheritance Mendel University of Agriculture and Forestry Brno (named after Mendel since 1994) Mendel Polar Station in Antarctica Abbey of St. Thomas in Brno Mendel Museum of Genetics Mendelian error References 1. ^ July 20 is his birthday; often mentioned is July 22, the date of his baptism. Biography of Mendel at the Mendel Museum (http://www.mendel-museum.com/eng/1online/room1.htm) 2. ^ a b c Bowler, Peter J. (2003). Evolution: the history of an idea. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520-23693-9. 3. ^ Gregor Mendel, Alain F. Corcos, Floyd V. Monaghan, Maria C. Weber "Gregor Mendel's Experiments on Plant Hybrids: A Guided Study", Rutgers University Press, 1993. 4. ^ a b c "The Mathematics of Inheritance" (http://www.mendel-museum.com/eng/1online/room2.htm) . Online museum exhibition. The Masaryk University Mendel Museum. http://www.mendel-museum.com/eng/1online/room2.htm. Retrieved Jan. 20, 2010. 5. ^ a b c "Online Museum Exhibition" (http://www.mendel-museum.com/eng/1online/) . The Masaryk University Mendel Museum. http://www.mendel-museum.com/eng/1online/. Retrieved Jan. 20, 2010. 6. ^ "The Enigma of Generation and the Rise of the Cell" (http://www.mendel-museum.com/eng/1online/room3.htm) . The Masaryk University Mendel Museum. http://www.mendel-museum.com/eng/1online/room3.htm. Retrieved Jan. 20, 2010. 7. ^ "Mendel's Garden" (http://www.mendel-museum.com/eng/8garden/) . http://www.mendelmuseum.com/eng/8garden/. Retrieved Jan. 20, 2010. 8. ^ Mendel, J.G. (1866). Versuche über Pflanzenhybriden Verhandlungen des naturforschenden Vereines in Brünn, Bd. IV für das Jahr, 1865 Abhandlungen:3–47. For the English translation, see: Druery, C.T and William Bateson (1901). "Experiments in plant hybridization" (http://www.esp.org/foundations/genetics/classical/gm-65.pdf) . Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society 26: 1–32. http://www.esp.org/foundations/genetics/classical/gm-65.pdf. Retrieved http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregor_Mendel Page 4 of 6 Gregor Mendel - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 8/1/10 11:30 AM 2009-10-09. 9. ^ Windle, B.C.A.; Translated Looby, John (1911). "Mendel, Mendelism" (http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10180b.htm) . Catholic Encyclopedia. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10180b.htm. Retrieved 2007-04-02. 10. ^ a b Carlson, Elof Axel (2004). "Doubts about Mendel's integrity are exaggerated". Mendel's Legacy. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-087969675-7. 11. ^ Mayr E. (1982). The Growth of Biological Thought. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 730. ISBN 0-674-36446-5. 12. ^ Fisher, R. A. (1936). Has Mendel's work been rediscovered? Annals of Science 1:115–137. 13. ^ Hartl, Daniel L.; Fairbanks, Daniel J. (1 March 2007). "Mud Sticks: On the Alleged Falsification of Mendel's Data" (http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1840063) . Genetics 175 (3): 975–979. PMID 17384156 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17384156) . PMC 1840063 (http://www.pubmedcentral.gov/articlerender.fcgi? tool=pmcentrez&artid=1840063) . http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1840063. Retrieved 2008-08-08. "[The] allegation of deliberate falsification can finally be put to rest, because on closer analysis it has proved to be unsupported by convincing evidence.". 14. ^ Novitski, Charles E. (March 2004). "On Fisher’s Criticism of Mendel’s Results With the Garden Pea" (http://www.genetics.org/cgi/reprint/166/3/1133) . Genetics 166 (3): 1133–1136. doi:10.1534/genetics.166.3.1133 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1534%2Fgenetics.166.3.1133) . PMID 15082533 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15082533) . PMC 1470775 (http://www.pubmedcentral.gov/articlerender.fcgi? tool=pmcentrez&artid=1470775) . http://www.genetics.org/cgi/reprint/166/3/1133. Retrieved 2010-03-20. "In conclusion, Fisher’s criticism of Mendel’s data—that Mendel was obtaining data too close to false expectations in the two sets of experiments involving the determination of segregation ratios—is undoubtedly unfounded.". Bibliography Cheryl Bardoe Gregor Mendel: The Friar who grew peas., HN Abrams, 2006. William Bateson Mendel's Principles of Heredity, a Defense, First Edition, London: Cambridge University Press, 1902. On-line Facsimile Edition: Electronic Scholarly Publishing, Prepared by Robert Robbins (http://www.esp.org/books/bateson/mendel/facsimile/title3.html) Robin Marantz Henig, Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, the Father of Genetics, Houghton Mifflin, May, 2000, hardcover, 292 pages, ISBN 0-395-97765-7; trade paperback, Houghton Mifflin, May, 2001, ISBN 0-618-12741-0 Robert Lock, Recent Progress in the Study of Variation, Heredity and Evolution, London, 1906 Vítězslav Orel, Gregor Mendel: the first geneticist, Oxford University Press. 1996, ISBN 0198547749 Reginald Punnett, Mendelism, Cambridge, 1905 Curt Stern and Sherwood ER (1966) The Origin of Genetics. Colin Tudge In Mendel's footnotes ISBN 0-09-928875-3 book about Gregor Mendel Bartel Leendert van der Waerden Mendel's experiments Centaurus 12, 275–288 (1968) refutes allegations about "data smoothing" James Walsh, Catholic Churchmen in Science, Philadelphia: Dolphin Press, 1906 Ronald A. Fisher, "Has Mendel's Work Been Rediscovered?" Annals of Science, Volume 1, (1936): 115–137. Discusses the possibility of fraud in his research. External links Mendel's Paper in English (http://www.mendelweb.org/Mendel.html) Mendel Museum of Genetics (http://www.mendelmuseum.muni.cz/en/) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregor_Mendel Page 5 of 6 Gregor Mendel - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 8/1/10 11:30 AM Mendel in Darwin's Shadow, by David Allen (http://www.macroevolution.net/mendel.html) at Macroevolution.net (http://www.macroevolution.net/index.html) Biography, bibliography and access to digital sources (http://vlp.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/people/data? id=per116) in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia entry, "Mendel, Mendelism" (http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10180b.htm) Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=OMIM) Augustinian Abbey of St. Thomas at Brno (http://www.opatbrno.cz/) A photographic tour of St. Thomas' Abbey, Brno, Czech Republic (http://biology.clc.uc.edu/Fankhauser/Travel/Berlin/for_web/Mendel_in_Brno.html) Johann Gregor Mendel: Why his discoveries were ignored for 35 (72) years (http://www.weloennig.de/mendel.htm) (German) This has the basics of Mendel and is more appropriate in style for a GCSE student (http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/science/add_aqa/celldivision/inheritance3.shtml) Masaryk University to rebuild Mendel’s greenhouse | Brno Now (http://brnonow.com/2009/02/university-to-rebuild-mendels-greenhouse/) "Gregor Mendel (1822–1884)" (http://www.accessexcellence.org/RC/AB/BC/Gregor_Mendel.html) . http://www.accessexcellence.org/RC/AB/BC/Gregor_Mendel.html. Retrieved 2008-01-22. "Biography of Gregor Mendel" (http://mendel.imp.ac.at/mendeljsp/biography/biography.jsp) . http://mendel.imp.ac.at/mendeljsp/biography/biography.jsp. Retrieved 2008-01-22. "Gregor Mendel: Planting the Seeds of Genetics" (http://www.fieldmuseum.org/mendel/) . http://www.fieldmuseum.org/mendel/. Retrieved 2008-01-22. "Gregor Johann Mendel" (http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=10997) . Find a Grave. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=10997. Gregor Mendel Primary Sources (http://www.thomasmore.edu/library/mendel_collection.cfm? group%20=The%20Mendel%20Collection) Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregor_Mendel" Categories: Geneticists | Religion and science | Botanists with author abbreviations | Augustinian friars | Roman Catholic scientist-clerics | Austrian Roman Catholics | Roman Catholic philosophers | Austrian biologists | Austrian botanists | People from Austrian Silesia | People from Brno | Silesian Germans | Moravian Germans | Austrian people of Czech descent | Deaths from nephritis | 1822 births | 1884 deaths This page was last modified on 23 July 2010 at 23:36. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. See Terms of Use for details. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization. Privacy policy About Wikipedia Disclaimers http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregor_Mendel Page 6 of 6