Internal Control 2006: The Next Wave of

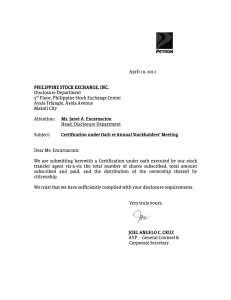

advertisement