Film Editing - Teacher Barb

advertisement

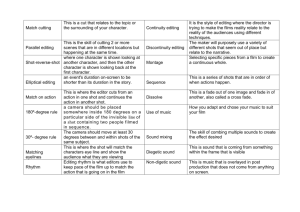

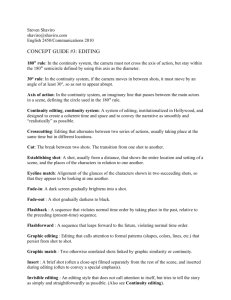

Chapter 6: Editing Chapter Overview Objectives: After reading this chapter, you should be able to • • • • • • • • • Understand the relationship between the shot and the cut. Describe the film editor’s major responsibilities. Explain the various ways that editing establishes spatial relationships between shots. Describe some of the ways that editing manipulates temporal relationships. Understand the significance of the rhythm of a movie and describe how editing is used to establish that rhythm. Distinguish between the two broad approaches to editing: editing to maintain continuity and editing to create discontinuity. Describe the fundamental building blocks of continuity editing. Describe the methods of maintaining consistent screen direction. Name and define the major types of transitions between shots, and describe how they can be used either to maintain continuity or to create discontinuity. Film Editing The first movies consisted of single shots, but filmmakers soon developed the technique known as editing to coordinate a series of shots into a coherent whole. Movies generally are shot out of continuity (in other words, very much out of chronological order), often in many takes. The resulting footage must later be organized into a form that will be comprehensible to the audience, create meaning, and perhaps evoke specific emotional and intellectual responses. If the shot is the basic unit of film language, editing is its grammar: for some filmmakers, it is the most important shaper of film form. Editing derives its power from the natural human tendency to interpret visual information in context. When two images (two shots, for example) are placed in close proximity to each other, we interpret them differently than we would have if we saw only one or the other image in isolation. Understanding the effects of editing on meaning, and having the vocabulary needed to describe the methods employed to achieve those effects, is the point of Chapter Six. At its most fundamental level, editing is the process of managing the transitions (called cuts) from one shot to another. Those transitions can be managed to produce a sense of continuity or of discontinuity. It’s important to understand the difference between these two goals, and to note that individual films can contain examples of both continuity and discontinuity editing. Editing that strives for continuity must carefully manage spatial and temporal relationships between shots to ensure that viewers understand the movement of figures in the frame and the progression of narrative information. One of the most fundamental conventions of continuity editing is the use of a master (or establishing) shot to establish for viewers the overall layout of a space in which a scene takes place. This shot, when followed by shots that are in closer implied proximity to subjects, makes it easy for viewers to understand relative positions of people and objects throughout a scene. The Kuleshov Effect Russian filmmaker and theorist Lev Kuleshov famously demonstrated the power of film editing and the viewer’s role in making sense of filmic space and cinematic time. When Kuleshov intercut an image of Russian actor Ivan Mozhukhin with shots of a dead woman, a smiling child, and a dish of soup, his point was that a spectator would imbue an identical shot with different meanings and feelings if it appeared within different contexts. In another demonstration, Kuleshov took shots filmed at different times and locations and assembled them into a logical sequence that viewers perceived as continuous in time, place, and action. This ability to create spatiotemporal continuity where none exists allows for the common production practice of filming out of sequence, across multiple locations and time periods, and in and out of the studio. Scissors and Glue Consisting of single shots, the earliest films required no editing. When filmmakers began using multiple shots to develop longer and more complicated stories, film editors became essential collaborators in the creative process. In the early silent era, editors were frequently women, such as Dorothy Arzner and Margaret Booth, who "cut" film with scissors or razors and took the edited scenes to a projection room for a director to view and critique. (In the late 1920s, by the way, Arzner moved from editing to directing movies—she was one of the few female directors in the Hollywood studio system of the ‘20s and ‘30s.) In 1924, the first Moviola editing machine was sold to Fairbanks Studios for $125. A small device similar to a projector, the Moviola included a small viewing lens instead of a projection lens and was handcranked. The device allowed editors to move film backward and forward at projection speed or any other speed they could control with their hands. From the late 1920s to the mid 1960s, Moviola dominated the market for film-editing equipment, developing newer models that handled sound and picture, ones that accommodated multiple picture takes, and even miniature devices for World War II journalists and combat cinematographers to use (Moviola history). From Upright to Flatbed Film-editing machines such as those first produced by Moviola and other manufacturers were called uprights because an editor could sit upright and edit footage. The next major innovation was the flatbed, a device that resembles a table and includes a television-like screen or two for reviewing. The flatbed enabled editors to lay longer reels flat on the editing surface; the high-speed, electrical motor enabled them to rewind and fast forward through long sections of film at higher speed than was possible with uprights. In addition, the flatbeds’ monitors made it possible for more than one person to review cut sequences. Filmmakers could now review and discuss scenes without going into a projection room. A Movie-within-a-Movie Primer on Editing the Old-Fashioned Way Brian DePalma's Blow Out (1981)—loosely adapted from Michelangelo Antonioni’s movie Blowup (1966), which focused on a still photographer—provides one of the best Hollywood treatments of sound- and picture-editing practices. John Travolta plays Jack, a sound-effects recordist and editor who works on low-budget horror films and television. While recording "wind" sounds for a sorority-house slasher picture, Jack hears (and records) a car crash into the river below him. He dives in, rescues a prostitute, but is too late to save presidential candidate Governor McRyan. Later, while listening to the recording of the crash, Jack hears an odd explosion, not quite right for a tire blowout. He carefully assembles frames of film shot at the scene by an amateur and published in a magazine, then synchronizes that film with his own sound recording. The result enables him to spot a flash of light (a gunshot?) that coincides with the sound of the supposed blowout. Enter Digital Editing The rise of digital, or nonlinear, editing systems began with video systems in the 1970s and accelerated as personal computers became more widely available in the 1980s and '90s. In 1989, Avid Technology began developing what would become the most successful digitalediting system on the market; today, Avid systems are used for the majority of editing done in television, film, and commercials. The Avid Film Composer, a $100,000+ software system, allows a level of freedom and access to footage that was not possible with the older editing systems. Some editors worry that digital-editing systems allow for so many possible versions of a scene that filmmakers can be overwhelmed by the options. Many editors who have been around long enough to have used several of the various editing technologies maintain that digital-editing systems increase the movement away from the solitary editor and toward collaborative editing that the flatbed systems began. Indeed, Avid now offers digital-editing software for online collaboration, allowing the editing room of the future to span states, countries, and continents. Timeline of Editing 1894 Fred Ott's Sneeze, the first complete film on record, consists of only one shot. 1899 Georges Méliès's Cinderella (Cendrillon) is one of the earliest films to use editing as an aid to narrative. It consists of twenty shots joined by straight cuts and intertitles. 1903 Edwin S. Porter's Life of an American Fireman is released in two different versions, one with nine shots and another with twenty. Another of Porter's films, The Great Train Robbery, is the first major use of parallel editing, crosscutting between two actions occurring at the same time but in different places. 1919 Lev Kuleshov begins an influential experiment in which he places an identical shot of an expressionless actor after each of three different shots (a dead woman, a child, and a plate of soup). After seeing the film, Kuleshov's students believe that the actor responds differently to each stimulus. Kuleshov thus shows how vital editing is to a performance. 1920 D. W. Griffith's Way Down East provides an early example of parallel editing and cinematic patterns. To heighten the drama in the climactic ice-break sequence, Griffith cuts between three different shots (the hero, the damsel in distress, and the peril) in an A B C A C B C A B C A C B C pattern. While continuity editing is one of Griffith's major contributions to the language of cinema, other filmmakers-Vsevolod Pudovkin, Sergei Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov, Aleksandr Dovzhenko, and Luis Buñuel prominent among them-shift away from creating logical, continuous relationships among elements within stories and instead create discontinuous (or nonlinear) relationships. 1924 The Moviola, a portable upright editing tool operated by foot pedals, is introduced. Complete with a built-in viewing screen, it allows sound and video to be edited, separately or together. 1926 The advent of sound movies profoundly affects all aspects of film production, including editing. 1927 Abel Gance introduces Polyvision, a process that uses three cameras and three projectors to show up to three events at the same time or display an ultrawide composition across three screens. He pioneers this technique, which predates widescreen by more than twenty-five years, in his film Napoléon. 1941 Orson Welles's Citizen Kane makes narrative use of discontinuity editing; the progression of Kane's life is shown multiple times but with different key events each time, presenting the audience with a scattered, non-chronological view. 1946 Establishing shots in Vincente Minelli's Meet Me in St. Louis use dissolves as transitions between prop photographs of locations and the "real" places. 1950 ACE, American Cinema Editors, an honorary society of motion picture editors, is founded. Film editors are voted into membership on the basis of their professional achievements, their dedication to the education of others, and their commitment to the craft of editing, and are thus entitled to place the honorific letters A.C.E. after their names in movie credits, just as cinematographers elected to the American Society of Cinematographers (ASC), place the letters A.S.C. after their names. 1954 Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window—about a man who, while watching his neighbors through his window, sees signs of a murder being committed—uses point of view shots and eyeline-match cuts. 1955 Ishiro Honda's Godzilla is reedited before its American release. New scenes are filmed and added with American actor Raymond Burr, including some that give the appearance of Burr interacting with characters from the Japanese portions (although none of the Japanese actors were present for the reshoots). 1968 The now-famous sequence in Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey in which a prehistoric human's bone weapon spinning in the air transforms into a space station rotating in space is perhaps the most audacious example of a match-on-action cut. 1977 George Lucas's Star Wars frequently uses wipes for transitions between scenes —an homage to classic science fiction movie serials such as Flash Gordon. 1979 In one of the greatest challenges to film editing in history, Francis Ford Coppola shoots 370 hours of footage for Apocalypse Now. Editors (supervised by Richard Marks) shape that footage into the initial release, which runs 153 minutes, a ratio of 145 minutes shot for every minute used. 1982 Carl Reiner's Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid, a tribute to 1940s film noir, intercuts shots from other films to give the appearance of the main character speaking to actors from forty years before. 1989 Avid introduces the Media Composer, a computerized device for nonlinear editing. 1994 Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction uses discontinuity editing for its overall narrative structure; the major events of the film occur out of sequence, so that the end of the story is actually in the middle of the film. 1998 In Tom Tykwer's Run Lola Run (Lola rennt), the rhythms of the editing match the energetic music, creating a hyperkinetic feel. Animation, live action, timelapse cinematography, slow- and fast-motion, various camera angles and positions, and so on, are cut together, using varying techniques (hard cuts, dissolves, jump cuts, and ellipses). Alex Proyas's Dark City, with an average shot length of 1.8 seconds, is one of the fastest-paced movies ever made. 2000 Christopher Nolan's Memento runs part of its story backward in color sequences and part of it forward in black-and-white sequences, creating a unique cinematic puzzle. 2001 With the aid of editor Walter Murch, Francis Ford Coppola recuts his 1979 film Apocalypse Now, adding forty-nine minutes of original footage along with new music. The new version, Apocalypse Now Redux, is truer to the filmmakers' original intentions. 2002 Aleksandr Sokurov's Russian Ark (Russkij kovcheg), which consists entirely of the longest take in film history (ninety-six minutes), is a tour de force of planning, choreography, and Steadicam camera movement. 2003 Virtually all filmmaking, from commercial features to student productions, now depends on nonlinear editing with digital equipment. Editing Techniques An ideal cut (for me) is the one that satisfies all the following six criteria at once: 1) it is true to the emotion of the moment; 2) it advances the story; 3) it occurs at a moment that is rhythmically interesting and "right"; 4) it acknowledges what you might call "eye-trace"—the concern with the location and movement of the audience's focus of interest within the frame; 5) it respects "planarity"—the grammar of three dimensions transposed by photography to two (the questions of stage-line, etc.); and, 6) it respects the three-dimensional continuity of the actual space (where people are in the room and in relation to one another). . . . Emotion, at the top of the list, is the thing that you should try to preserve at all costs. If you find you have to sacrifice certain of those six things to make a cut, sacrifice your way up, item by item, from the bottom. Walter Murch, In the Blink of an Eye, 18–19 180 degree rule: an imaginary line that indicates the direction people and things face when viewed through the camera. When you cross the line with the camera, you reverse the screen direction of your subjects. Continuity Editing: a style of editing (now dominant around the world) that seeks to tell a story as clearly as possible and achieve: logic, smoothness and sequential flow, temporal and spatial orientation of viewers to what they see onscreen, flow from shot to shot, and filmic unity. Discontinuity Editing: a style of editing---less widely used than continuity editing, often but not exclusively used in experimental films-that joins shots A and B to produce an effect or meaning not even hinted at by either shot alone. Dissolve/Lap Dissolve: shot “B” gradually appears over shot “A” and replaces it- often implying passing of time. Ellipsis: the most common manipulation of time through editing is an omission of the time that separates one shot from another. Fade: transition from black or to black. Flashback: the interruption of the chronological plot time with a shot or series of shots that show an event that has happened earlier in the story. Flashforward: the interruption of present action by a shot or series of shots that shows images from the plot’s future. Freeze Frame: step printing of an image creating a still much like an exclamation point. Iris Shot: special small circle wipe line—it can grow larger or smaller (iris in or iris out). Graphic Match: provides continuity by matching a shape, color, or texture across an edit. Jump Cut: a disorienting ellipsis between shots. Kuleshov Effect: Russian filmmaker and theorist Lev Kuleshov famously demonstrated the power of film editing and the viewer’s role in making sense of filmic space and cinematic time. When Kuleshov intercut an image of Russian actor Ivan Mozhukhin with shots of a dead woman, a smiling child, and a dish of soup, his point was that a spectator would imbue an identical shot with different meanings and feelings if it appeared within different contexts. In another demonstration, Kuleshov took shots filmed at different times and locations and assembled them into a logical sequence that viewers perceived as continuous in time, place, and action. This ability to create spatiotemporal continuity where none exists allows for the common production practice of filming out of sequence, across multiple locations and time periods, and in and out of the studio. Master Shot: defines the spatial relationships in a scene. Match Cuts: those in which shot A and shot B are matched in action, subject graphic content, or two characters’ eye contact. Montage is from the French verb “monter” which means “assemble or put together.” Montage =“editing” in French. Montage refers to the various forms of editing in which ideas are expressed in a series of quick shots. Montage was first used in the 1920s by Soviet masters like Eisenstein, Vertov, Pudovkin and in 1930s Hollywood to condense a series of events. Parallel Editing: two or more actions happening at the same time in different places. Point-of-View Editing: editing of subjective shots that show a scene exactly the way the character sees it. Wipe: transitional device, often indicates change of time, place or location. Sound Effects Editing Many discussions of editing emphasize images over sound, neglecting the fact that every feature film has sound editors as well as picture editors. In their book-length conversation about, among other things, sound editing and picture editing, writer Michael Ondaatje and editor and sound designer Walter Murch make clear how important sound effects editing can be to the overall effect of a film, in this case of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972): For every splice in the finished film there were probably fifteen "shadow" splices—splices made, considered, and then undone or lifted from the film. But even allowing for that, the remaining eleven hours and fifty-eight minutes of each working day were spent in activities that, in their various ways, served to clear and illuminate the path ahead of us: screenings, discussions, rewinding, re-screenings, meetings, scheduling, filing trims, notetaking, bookkeeping, and lots of plain deliberative thought. A vast amount of preparation, really, to arrive at the innocuously brief moment of decisive action: the cut—the moment of transition from one shot to the next—something that, appropriately enough, should look almost self-evidently simple and effortless, if it is even noticed at all. Walter Murch, In the Blink of an Eye, 4 Just as the graphic match exploits the Kuleshov effect to create a new whole out of somehow similar but not inherently related shots, so the editing together of shots and sounds affects our perception of both components. In this way, sound editors help lift scenes and entire films onto new levels of meaning. Conclusion Where, how and when cuts are made depend on the style of the film as a whole. Editing style boils down to a question of how the filmmaker relates to the world he/she is portraying. Key Question: Should the filmmaker use pieces of raw material (time, space action) to construct meaning or leave them unmanipulated and genuine? Barsam, Richard. “Editing.” Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. Second edition. New York: WW Norton and Company, 2007. Pages 195 - 236.