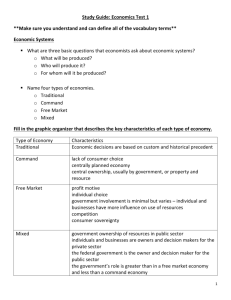

Financial Inclusion of the Poor in Bangladesh: Challenges

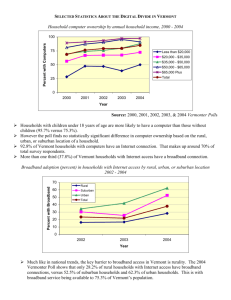

advertisement