Hatsune Miku, the Emergence of Global Value Co

advertisement

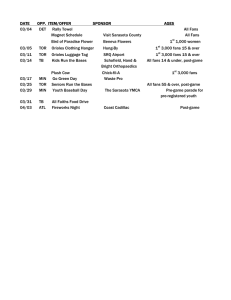

Hatsune Miku, the Emergence of Global Value Co-creation Abstract Our study explores how value is created in the context of Hatsune Miku (HM), a phenomenal virtual celebrity originated in Japan. The study employed an evolved-grounded-theory analytical approach to analyze a range of data including interview with the CEO of HM developer, technical details of the HM software and more than two hundred fan-generated comments online. Our analysis from three perspectives of technicality, business model and consumer experience has found that the co-created value of HM goes beyond individual technical developers and individual consumer capacities. With Crypton Future Media (CFM) having used the advanced voice synthesizing technology innovated by Yamaha to create HM, our evaluation indicates that the value co-creation process - reflected within a complex, cotrusted business model with rich and salient socio-cultural attachment emerging within multiparty involvement - are main drivers of HM’s success. The rising fame and fandom of HM lies on two underlying factors: the power of involving multi-stakeholders and multi-processes in co-creating the desired HM production, and the power of socio-cultural appropriation and legitimation of the authenticity of HM expressed by the anthropomorphic characterization of HM as the souled idolation ontology of their fans. Keywords: value; co-creation; virtual celebrity; singing synthesizer; business model; anthropomorphic agent 1 Introduction As of August 2013, Hatsune Miku (HM) has over 100,000 released songs, 170,000 uploaded YouTube videos and one million created artworks, with over 900,000 fans in Facebook (Crypton Future Media, 2013). She has sold out “live” concerts from Tokyo to Los Angeles, stars in her own video game project Diva produced by SEGA Games which has sold more than 1 million copies (SEGA, 2012). She has been “hired” to advertise some of the world’s top brands including the launch of Toyota’s 2011 Corola series cars (Sweet, 2011) Google’s Chrome advertisements in Japan (Google Chrome Japan, 2011) and most recently in 2013, Dominos Pizza Japan’s iPhone App (Domino's, 2013). She has been the featured topic of news stories from the UK’s BBC to America’s CBS News, and has captivated the hearts of fans around the world. HM is not human and in some ways could be seen as being similar to popular animated characters such as Mickey Mouse or Hello Kitty. However, her rise to stardom and global fame has developed in a completely new and unique way denoting a testament to the growing importance of value co-creation in modern marketing practices. In fact, her body of work is not "created" by any one individual, but is the sum total of many different professional and amateur collaborators in Japan and around the world. Contributing to the area of innovation through value co-creation (Vargo et al, 2008), the paper investigates the nature, process and configuration of the co-creative interaction between consumers, related communities and firms in the context of virtual celebrity of HM from the perspectives of technicality, business model and virtual consumption experience. The next sections will discuss and review related literatures of the three perspectives, followed by method, analysis and discussion. The paper concludes with implications and future research. Theoretical background Re-focusing on value and its creation Traditionally, from consumer view value is concerned with perceived desirable outcomes of consuming an offered product or service (Oliver, 1999). It is an experience within specific context with interactive, relativistic, and preferential characteristics (Holbrook 1994); it has tangible and intangible aspects (Pine & Gilmore, 1998; Skytte & Bove 2004); and when the desired outcome is achieved, high involvement will develop (Woodruff 1997). From the provider/firm view, value is the essence firms aim to deliver that in turn brings financial and related benefits to them, as well as to the consumers they serve and to society at large (e.g. Gundlach and Wilkie, 2009). More specifically the AMA 2007’s definition indicates three main components of value: value originator, value offering, and customers at large. Thus, from these views the firm has been positioned as the main, sole value originator and creator. However, these views have not yet embraced the potential for value to be developed and built together by firms, their customers and other potential value contributors. In fact within the last decade, the meaning of value and the process of value creation have rapidly been shifting from a product- and firm-centric view to the one that incorporates personalized consumer experiences (Cristiano, Liker, & White, 2000) with the increasingly important role of consumers who are networked, empowered, and active in co-creating value with the firm (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004; Payne, Storbacka & Frow, 2008). In this view value is cocreated by the consumer and the firm; the co-creation processes form the basis of such value creation; and individual consumers are central to the co-creation experience (Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2004). The following sections will review literature of each of the three perspectives of technicality, consumer experience and business ecosystem in order to outline the sources of value. Technical background: Vocaloid singing software Over the past five decades researchers have continued working on creating the technology to enable computers to sing. However, in most cases the resulting voices have sounded 2 mechanical, and the performances lack feeling. Musicians were already able to create convincing instrument simulations using state-of-the-art synthesizer and sampling technologies, but high-quality simulation of that ultimate instrument—the human voice— remained elusive. The situation finally changed in 2003 when Yamaha launched Vocaloid (version 1/V1), the world's first serious commercial singing synthesizer—driving the technology out of the research world and into the real one (Yamaha, 2012). The Vocaloid technology consists of three key parts: the singer library, which stores the sound fragments broken from recording of a live singer, such as vowel, consonant sounds and pronunciations; the score editor, which is an interface to allow user to enter lyrics and notes, and to edit and adjust these as necessary to get the desired nuances; and the synthesis engine, which concatenates the voice elements to generate the singing voice, by splicing vocal fragments in the frequency domain. This signal processing part was developed through a joint research project led by Kenmochi Hideki at the Pompeu Fabra University in Spain in 2000 (Anon, 2013). By improving the sound quality from the synthesis engine and the score editor according to user feedback, a new version, Vocaloid version 2 (V2) was launched in 2007 (Yamaha, 2012). Sapporo-based Crypton Future Media (CFM) adopted V2 to create HM, which soon became a major hit in Japan with a boom in the creation and dissemination of a range of HM’s products (Yamaha, 2012). Now, with vocaloid available, the value co-creation of music products by non-musicians are made possible. Virtualized consumer experience Enjoying HM can be seen as a form of virtualised consumption that signifies experiential pleasures it may bring to consumers not from materialised consumption or tangible encounter. Conceptually this virtualized consumer experiences with limited material existence challenges classical theories of consumption based on rational or utilitarian needs (Firat and Dholakia 1998). Similarly Kline, Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter (2003) proposed that virtualised consumption represent the latest stage of the subtle transformation of consumption practices from utilitarian emphasis to pursuing aesthetic, emotional, symbolic and experiential value. As consumer culture increasingly moves away from the material ingredient, the experiential orientation put individual consumers as a main creative power that reconfigure the process, output and the types of consumption practices. Conceptually virtualised consumption can be seen as rooted in experiential consumption theory that signifies feeling, fun and fantasy as essential element of experiential consumption making it distinct from utilitarian consumption (Holbrook and Hirschman 1982). Similarly related work (e.g. Baudrillard, 1998; Campbell, 1987; Featherstone, 1992; Lee, 1993) conceptualize consumption as a symbolic, aesthetic, imaginary experience. Later, our analysis and discussion used these characteristics to identify the salient values experienced by HM fans and the corresponding creation processes. Business ecosystem model Exploring the underlying ecosystem within which a business operates is one rapidly evolving branch of epistemological academic inquiry within the larger, multi-disciplinary field of Systems Thinking. Such thinking allows researchers to first conceptualize and then optimize large, complex and interrelated systems and is especially well-suited for the study of highly complex co-creative systems such as the one that has developed around HM. Such analysis of systems was first formalized within the operations research literature with Bertalanfy's Systems Theory (1956). This was then enhanced and expanded upon by Churchman (1968) and Checkland (1972) who focused on "real world" problems and issues, and their work was brought into business research most effectively through Porter's conceptualizations of firm's internal value chains and external value systems for further mapping strategy development (Porter, 1985). Senge (1990) further enhanced the role of systems thinking within business 3 research and practice as the 5th of his five disciplines, again stressing the overall system within which firms operate as central to successful firm performance. Moore (1996) first introduced the term "business ecosystem" to describe the interactions between firms, competitors, customers and other stakeholders to resemble biological ecosystems. Later in Japan, Natsuno (2003) and the leadership team of NTT DoCoMo applied similar "ecosystem thinking" to design Japan's i-mode mobile Internet service. Levien (2004) has highlighted the strategic importance of using such ecosystems for planning and strategy development, which we will use as one of our three means of inquiry into the value of HM. Methodology We explore the characteristics and process of value co-creation of HM via analyzing the originator-producer, the product and the consumers using three perspectives of technicality, consumer experience and business model. As this is the first academic inquiry into the HM phenomenon, we employed an evolved-grounded-theory approach (Corbin & Strauss, 1990; Glaser and Strauss, 2009), to enable theoretical insights to emerge from each of the three perspectives, which insights we hope will serve as the foundation for further theorization. The following data and information collected in 2012 to 2013 were included for evaluation and analysis: (1) a 90-minute interview with Hiroyuki Itoh, the CEO of CFM, regarding his views on value co-creation and development of HM, (2) technical details of the HM software that we purchased to conduct a series of technical tests, and (3) the analysis of 200+ fan-generated comments from online portals and websites including (a) CBS News (Johnson, 2012), (b) Facebook (e.g. https://www.facebook.com/pages/Hatsune-Miku/10150149727825637) and (c) one of the most prominent HM fan websites (e.g. www.mikufan.com). Results and Discussions: HM value co-creation characteristics and process Technicality Singing Synthesizer enhanced by Web Technology Technically HM is a singing synthesizer application with a humanoid persona created by CFM using Yamaha's singing synthesizing technology of Vocaloid version 2 (V2). The boom of HM has also been driven by web, through which different creators such as songwriters, song creators, illustrators and computer graphic creators interact and co-develop the products (Hamasaki, Takeda & Nishimura, 2008). With the increase of remix works and the steadily growing global demands, CFM engages consciously in the promotion, support and cultivation of the HM community. CFM launched a website called Piapro (which is short for “Peer Production) (http://piapro.jp) three months after the release of the HM software. This website is a consumer-focused media platform where users can collaborate and share their creations. Users can upload their music, illustrations and lyrics onto Piapro. The works must be for noncommercial use and users are encouraged to show their gratitude to the original creators by sending the messages on Piapro. More than 600,000 works have been posted on Piapro. Without the rapid development of contemporary web technology, this activity wouldn’t have occurred. Consumer experience Socio-cultural attachment Since the launch of HM, a profound passionate relationship between HM and her fans has emerged (Aroean and Sugai, 2013). Our analysis further indicates that the socio-cultural attachment has been generated because HM is simultaneously stimulating, actualizing, experimenting and collaborating. HM is stimulating because it gives the desired freedom for consumers using resources and experiences so that they can obtain an (representative) ability to sing. In terms of actualizing, HM fans can actualize their latent desire in making and 4 performing songs they like others to listen which could not be expressed in any other manner. Lyrics, types of music, types of voice tone, and dancing style performance are the productions where consumers may enact their dreams in musicality and singing realms. HM fans actualize their ideal imaginations or fantasies, like being a great composer or a choreographer that possess the ability to compose a fantastic song and to create a singing performance. Regarding experimenting, HM fans enjoy experimentally exploring and combining different features available, including adopting different kinds of music, lyrics and voices, even possible for unable music individuals. Adopting the concept of playfulness (Aroean, 2012), the stimulating-actualizing-experimenting-collaborating may be regarded as a specific type of symbolic interaction where the fans freely and enjoyably express their skills through creative, mental activity of producing HM singing productions. This is because the situation with the stimulating-actualizing-experimenting-collaborating properties may only happen where profound symbolic exchanges exist. Furthermore, as this highly abstract, symbolic interactive situation of creating HM productions exists within a collective, co-creative environment among HM fans, the attachment resulted is unsurprisingly rich with Japanese socio-cultural values. Business model As outlined in Figure 1, the ecosystem within which HM was created and through which money, creativity, content and awareness flow: Fig. 1 Value co-creation map Beginning from the original vocaloid patent holder, (1) Yamaha Corporation licenses the fundamental technology patents to (2) CFM exchange for licensing fees. Then in turn, CFM has integrated the image and voice of HM to their own pre-packaged vocaloid software which they sell to both professional and amateur (3) Music Creators. CFM sells this software both directly from its own proprietary website as well as through online and offline retailers. The 5 interactions between these three main players create a standard value exchange, in which the producers (1) and (2) jointly accrue value from the sales of software to (3) music creators. And in turn, the music creators obtain value through the use of the software product to create customized musical works. Music creators then post their creations to (4) commercial websites including YouTube, Nico Nico Douga, and CFM’s Piapro. Once these original songs are shared through these websites, other fans (5) who would like to enhance upon the original works created by the music creators then add additional animations or lyrics to these works, and once again re-post them on one of the commercial websites. Such hedonic valuecreation exercises have also been well explored in the extant marketing literature (Gentile et al., 2007). But in an ecosystem built around a global music star, we also see the inclusion of (6) Professional Industry Players such as Sega and Kadokawa Publishing within the cocreative environment. These players have their own special licensing relationships with CFM, and simultaneously aim to discover the most popular videos through (4a) commercial and (4b) fan sites. Once they have found appropriate content, these players will either license these from their creators or work directly with other professional creators to develop unique content. This content is then used to develop stand-alone (7) Marketable products such as concert events, Game Software, CDs and DVDs to sell to fans not only in Japan but (8) globally. And as the popularity of HM continues to grow both on and offline, an increasing number of (9) new and prospective end users are brought into the ecosystem, becoming paying fans or even collaborators and co-creators themselves. In sum, the map explicates what, when and how the values - e.g. music, lyrics, and animation contributed to the building of HM community and marketable end-products such as concert - created and added by different contributors. Conclusion, implications and future research Through examination of technicality, business model (eco-system) and consumer virtual experience, we identify that value co-creation of HM reflects a profound shift of consumption to virtualized consumption culture and socio-psychology. As such, the underlying force of the fame and fandom of HM lies on two things: the power of involving multi stakeholders and multi-process in co-creating the desired HM production, and the power of socio-cultural appropriation and legitimation of the authenticity of HM demonstrated by the anthropomorphic characterization of HM as a production of the souled idolation ontology. Theoretically, the findings suggest a number of implications. First, trust is strongly implied here, that HM has been used for common, good purpose, i.e. facilitating and enabling musical expressions from consumers, including those with no singing ability. Second, voluntarism or non-profit motive, probably more than simply altruism, exists, especially from animationlyric enhancers (no. 5 in Figure 1). Arguably, the enhancers, who are experts in their areas, have done this for free simply because of passion, enjoyment and fun. Third, using the concept of playfulness (Aroean, 2012), playfulness is fully facilitated here where fans enjoy symbolic interactions by and among themselves in freely expressing their skills. A number of practical implications exist. First, in the context of virtual product, innovation that emulates the cultural essence of a society offered with limited reservation of rights may become a business model trend. The market grows due to empowering individual to coinnovate and co-create the end products and production. Second, firms may initiate ‘basic’ software - rather than a completed, fully furnished one - that enables further open, voluntary, co-creation process of production. In the long run, the initiating firm will still harvest its investment soundly. Third, the community develops then acts as active marketers for the product or character, which is another valuable ‘return’ for the investing firm. While HM is originated and rich with Japanese socio-cultural values, her fame apparently goes global. Therefore, in the future, research investigating how and why several cultures or 6 nations enjoy and embrace HM is important. Future research may also investigate similar product to HM that thrives in different culture for building a universal co-creation model in the context of virtual product. Another route might be to study co-creation community within the context of creative industry in relation to their social profile and expertise. 7 References Akimoto, A. (2012). Freeware has animators dancing to the Hatsune Miku beat. Available at http://www.japantimes.co.jp/life/2013/02/20/digital/freeware-has-animators-dancing-tothe-hatsune-miku-beat/#.UlfC4lCsiSo (accessed 1 May 2013) Anon (2013). Vocaloid. Available at https://sites.google.com/site/vocaloid657436578/home/culture (accessed May 12, 2013) Aroean, L. (2012). Friend or foe: In enjoying playfulness, do innovative consumers tend to switch brand? Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 11(1): 67–80. Aroean, L. and Sugai, P. (2013). An analysis of anger responses within the context of virtualized consumption of Hatsune Miku. Advances in Consumer Research (forthcoming) Baudrillard, J. (1998) The consumer society: Myths and structures. London: Sage Bertalanfy, L.V. (1956). General systems theory. General Systems Yearbook 1: 1-10 Campbell, C. (1987). The romantic ethic and the spirit of modern consumerism. London: Blackwell-IDEAS. Checkland, P.B. (1972) Towards a systems-based methodology for real world problem solving. Journal of Systems Engineering, 3(2), 87-116. Churchman, C.W. (1968). The systems approach. New York: Dell Corbin, J. M., and Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative sociology, 13(1), 3-21. Cristiano, J. J., Liker, J. K., and White, C. C. (2000). Customer‐Driven Product Development Through Quality Function Deployment in the US and Japan. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 17(4), 286-308. Crypton Future Media (2013). Who is Hatsune Miku? Available at http://www.crypton.co.jp/miku_eng (accessed May 12, 2013) Domino's Pizza Japan (6 March 2013) ドミノ・ピザ「Domino's App feat. 初音ミク. Available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gW2D_Votd2Y (accessed 30 September 2013) Featherstone, M. (1991). Consumer culture and postmodernism. UK: Sage Publications. Firat, A. F. and Dholakia, N. (1998). The making of the consumer. In A. Fuat Firat & Nikhilesh Dholakia (Eds.), Consuming People: From political economy to theaters of consumption (pp. 13-20). London, UK: Routledge. Gentile, C., Spiller, N. and Noci, G. (2007). How to Sustain the Customer Experience: An Overview of Experience Components that Co-create Value With the Customer. European Management Journal, 25(5), 395-410. Glaser, B. G., and Strauss, A. L. (2009). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Piscataway: Transaction Books. Google Chrome Japan, (14 December 2011) Google Chrome: Hatsune Miku (初音ミク) Available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MGt25mv4-2Q (accessed September 30, 2013) Gundlach, G. T. and Wilkie, W. L. (2009). The American Marketing Association's new definition of marketing: Perspective and commentary on the 2007 revision. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 28(2), 259-264. Hamasaki, M., Takeda, H. & Nishimura, T. (2008). Network analysis of massively collaborative creation of multimedia contents. Holbrook, M. B. (1994). The Nature of Customer Value: An Axiology of Services in the Consumption Experience, pp. 21–71 in Service Quality: New Directions in Theory and Practice,Roland T. Rust and Richard L. Oliver, (Eds.), Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of consumer research, 132-140. 8 Itoh, H. (2013). A formal interview by Feng Tian and Tim Craig with the CEO of Crypton Media, in May 2013 Johnson, B. (2012). Hatsune Miku: The world’s fakest pop star. CBS News. Available at http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-205_162-57547707/hatsune-miku-the-worlds-fakest-popstar/ (accessed 4 January 2013) Kline, S. ,Dyer-Witheford, N. & de Peuter, G. (2003) Digital play: The interaction of technology, culture, and marketing. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press Lee, M. (1993). Consumer culture reborn: The cultural politics of consumption. Routledge. Levien, R. (2004). The keystone advantage: What the new dynamics of business ecosystems mean for strategy, innovation, and sustainability. Boston: Harvard Business Press. Moore, J. F. (1996). The death of competition: leadership and strategy in the age of business ecosystems. New York: Harper Business. Natsuno, T. (2003). i-mode wireless ecosystem. New York: John Wiley & Sons Oliver, R. L. (1999). Value as excellence in the consumption experience, in M.B. Holbrook (Ed), Consumer value: A framework for analysis and research, 43-62, New York, Routledge. Payne, A. F., Storbacka, K., & Frow, P. (2008). Managing the co-creation of value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 83-96. Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review, 76, 97-105. Pink, D. H. (2007). Japan, ink: Inside the manga industrial complex. Available at http://www.wired.com/techbiz/media/magazine/15-11/ff_manga (accessed on 15 May 2013). Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive Advantage. New York: The Free Press. Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5-14. SEGA (2012) "初音ミク - Project DIVA』シリーズ累計出荷数 100 万本突破記念キャン ペーン, Available at http://miku.sega.jp/campaign/million/ (accessed 30 September 2013) Senge, P. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and science of the learning organization. New York: Currency Doubleday. Skytte, H., & Bove, K. (2004). The concept of retailer value: A means‐end chain analysis. Agribusiness, 20(3), 323-345. Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1994). Grounded theory methodology. Handbook of qualitative research, 273-285. Sweet, Y. (8 July 2011), Hatsune Miku - Toyota Corolla - All spots compilation. Available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UaA2liN9LKM (accessed 30 September 2013) Woodruff, R.B. (1997), “Customer value: the next source for competitive advantage”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 25 No. 2, pp. 139-53. Yamaha (2013). Vocaloid, 10th anniversary. Available at http://www.vocaloid.com/en/about/ (accessed May 12, 2013) 9