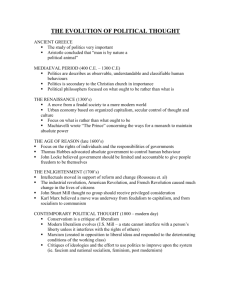

"The Politics of Recognition"

advertisement