The privatisation of British Rail: a study in organisational

advertisement

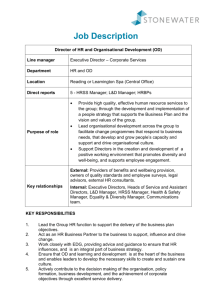

ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE RESEARCH UNIT (AFRU) The fragmentation of a railway: A study of organisational change in British Rail *David Tyrrall **David Parker November 2001 01/6 ISBN 0 7492 45484 © The Open University © David Tyrrall, David Parker © Aston Business School * The Open University Business School, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA Tel: (+44) 1908 659285 Fax: (+44) 1908 655898 Email: d.e.tyrrall@open.ac.uk ** Aston Business School, Aston University, Birmingham B4 7ET Tel: (+44) 121 359 3611 Fax: (+44) 121 333 3474 Email: d.parker1@aston.ac.uk Abstract Privatisation has received much attention from economists and political scientists, but surprisingly little from management academics. This paper considers British Rail from strategic and organisational perspectives, in the context of a long period of commercialisation of the corporation leading up to privatisation. The changes involved are analysed using the Laughlin (1991) and Parker (1995a) frameworks. The resulting analytical framework is used reflexively and the model of organisational change is augmented to include change pathways termed ‘fragmentation’ and ‘imposed evolution’. It is intended that this model should be of wider applicability not only to the study of public sector organisations that have undergone or are undergoing commercialisation and privatisation, but to other forms of major organisational change. 1. Introduction Privatisation has received much attention from economists and political scientists, but surprisingly little from management academics. The economic case for privatisation is predicated on the belief that resources will be more efficiently deployed in the private than in the public sector (Vickers & Yarrow, 1988; Bös, 1991; Boycko, Shleifer & Vishny, 1996; Martin & Parker, 1997). If privatisation is to succeed, however, this implies major changes in how organisations and activities are managed and structured, including changing the ‘organisational culture’ (Parker, 1994, 1995a). This paper considers the privatisation of British Rail (BR) from strategic and organisational perspectives and in the context of a longer period of commercialisation of railway management. BR was restructured from the late 1970s onwards and was privatized between 1995 and 1997. In this paper, these changes are analysed using the Laughlin (1991) and Parker (1995a) frameworks. Laughlin (1991, p. 223) emphasises that in understanding organisational change there is 'still a need for further case studies, and additional conceptualisation to clarify … why particular pathways (of change) are followed'. Broadbent (1992, p. 365), in the context of the same analytical framework, adds that ‘study of why organisations fragment ... would be a fruitful line of enquiry.’ Within the specific context of privatisation, Parker (1995a, p. 45) points out that 2 ‘surprisingly little research has been undertaken into what happens within organisations when they are (being) privatised’. The research reported below is intended to address these issues by undertaking an analysis of the changes in BR leading up to privatisation. The analytical framework is used reflexively to develop a revised approach to organisational change. While change during privatisation can be more dramatic than some other forms of organisational transformation, the model is not intended to be exclusively applicable to privatisation but to have wider applicability. The paper is timely in the context of current concern about mismanagement of the railways, the financial collapse of Railtrack, and the Labour Party’s espousal of increased private provision of public services. The paper is structured as follows: section one develops the analytical framework in which BR is assessed. Section two looks at the nature of change in BR from the late 1970s until privatisation. Finally, the change process in BR is assessed and the main conclusions are presented in Section three. 2. The Analytical Framework Laughlin (1991) provides a tripartite framework for the analysis of organisational change, by classifying organisational characteristics under three broad elements (Figure 1): namely, Interpretive Schemes (the underlying values of organisational members), Design Archetypes (organisational structures and systems) and Sub-systems (tangible elements of the organisation such as people or buildings). Importantly, the three elements must be in balance with one another to ‘bind the organisation together and make it a coherent whole’ (Laughlin, 1991, p. 213). This form of tripartite analysis is not unique to Laughlin (1991) and other approaches using different levels of abstraction can be found, for example, in Popper (1979, cited in Willmott, 2000) and Schein (1984). In this study, the Laughlin (1991) model is preferred because it was specifically framed for and has been extensively applied to the analysis of organisational change. Changes in organisational balance are particularly likely if the 3 environment changes in ways hostile to the organisation, and delivers a disturbance to it. Laughlin (1991) posits four pathways of organisational change: Rebuttal: a morphostatic (first order) change, which leaves all aspects of the organisation unchanged; Reorientation: another essentially morphostatic change, which may alter the subsystems or even the design archetype, but leaves the interpretive scheme untouched; Colonisation: a morphogenetic (second order) change, where environmental disturbance initially leads to a change in design archetype. This is illustrated in Figure 1 by the movement from DA1 to DA2, then to sub-systems, SS1 to SS2, and interpretive schemes IS1 to IS2. The result is a new balance within the organisation around a ‘new underlying ethos’ (Laughlin, 1991, p. 219); Evolution: another morphogenetic change, where environmental disturbance leads to rational internal discussion and agreed change to interpretive schemes over a period of time, with resultant changes to design archetypes and sub-systems. Interpretive Scheme Interpretive Scheme (IS) 1 (IS) 2 Balance Change new Process balance Disturbance / Design Archetype Change Design Archetype Jolt / Kick (DA) 1 Process (DA) 2 Balance Change New Process balance Sub-systems Sub-systems (SS) 1 (SS) 2 Figure 1: Morphogenesis (second order change): colonisation (after Laughlin, 1991) 4 The model has an intentionally recursive or reflexive nature, in that new studies analysed based on the model are used to further modify and develop it. Broadbent (1992), Laughlin, Broadbent, Shearn, Willig-Atherton (1994a), Laughlin, Broadbent and Willig-Atherton (1994b), and Broadbent and Laughlin (1998) examine morphostatic (essentially reorientation) pathways within smaller public organisations, as does Richardson, Cullen and Richardson (1996) within a small company context. There have been fewer such studies involving the context of large organisations. Laughlin (1991) finds reorientation in the Church of England and draws on Dent (1991) to illustrate the process of colonisation within British Rail. In each of the aforementioned studies, the analysis of changes in design archetypes is largely restricted to changes to accounting and financial systems. Clark and Soulsby (1995) introduce issues of structure and strategy to their analysis, but in a relatively informal manner to demonstrate how major Czech engineering enterprises followed a reorientation pathway. Other studies of smaller organisations, such as those by Slack and Hinings (1994) and Kikulis, Slack and Hinings (1995) on Canadian sports organisations and Cooper, Hinings, Greenwood and Brown (1996) on Canadian law firms, using a similar but not identical framework, with more emphasis on structural phenomena, find evidence for both colonisation and the persistence of previous interpretive schemes. In all of these cases, the organisations survived the environmental disturbance in question, with much or at least some of their interpretive schemes intact, thus confirming Laughlin’s (1991, p. 217) suggestion that ‘any interpretive scheme … [may accept] a number of different design archetypes without the coherence of organisational life being substantially challenged.’ The present study adds to this literature by: • augmenting the Laughlin (1991) schema with a more formal application of categories drawn from structural analysis in order to • investigate a pathway of colonisation, and • posit pathways of ‘fragmentation’ and ‘imposed evolution’1 • within a large organisation, 1 Related, although not identical ideas are raised in the theoretical literature (Dunphy & Stace, 1988; Laughlin, 1991; Broadbent, 1992), and are less explored empirically. 5 • which did not survive. The structural approach to organisational analysis is in the classical tradition (Pennings, 1992). Within this tradition, contingency theory holds that an organisation’s structure and control systems are contingent upon various aspects of its goals and environment (Dent, 1996), including ownership. Appropriate choices of organisational structure and management objectives enhance organisational effectiveness and promote organisational survival. Thus a contingency framework seems to provide an appropriate means of analysing organisational characteristics (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967; Pugh & Hickson, 1976). Parker (1995a) provides a contingency framework to analyse contrasting or stereotypical organisational characteristics appropriate to public and privatized organisations, under six headings: goals, nature and location of the business, structure, management, reporting systems, and labour. The framework is not intended to specify any one pathway between organisational states. Nor does it place any weighting of importance on the six categories. In this sense the approach is quite limited. Nevertheless, it provides a starting point for our analysis, where the intent is to investigate pathways of change. In this paper, Parker’s framework is augmented by a number of additional organisational characteristics that may be important in determining successful organisational change; namely, cultural paradigm, boundary systems, strategic style, and quantity of information processed. Moreover, this framework is combined with Laughlin’s model. Therefore, this study describes: Interpretive Schemes: as including the ownership, goals, cultural paradigm and boundary systems of the organisation; Design Archetypes: as including the organisational structure, strategic style, management style and management control systems, and; Sub-systems: as including the quantity of information processed and human resources. 6 Table 1 summarises the issues relevant to the analysis of BR under the above headings. These issues are discussed below. Table 1: Organisational change in British Rail before/during privatisation: a summary Period Interpretive Schemes Goals, Mission, Beliefs, Values and Norms (Dent, 1991: Laughlin, 1991; Parker, 1995a) BR in the 1970’s BR in the 1980’s BR in the 1990’s Multiple, sometimes vague and conflicting (‘public interest’) Social Railway Public interest but with increased business revenues Business Railway Entrepreneurial, unidimensional (profit) Ownership Cultural Paradigm (Siehl & Martin, 1990) Public Integration Public Differentiation Profitable Business Public to private Ambiguity Boundary Systems (Simons, 1995) Nature and location of business politically constrained Equity, accountability and probity More freedom for management with reduced government intervention Nature and location of business commercially determined Centralised, hierarchical functional structure Cost centres Mechanistic Matrix to divisional Separate businesses Strategic Planning Strategic control Design Archetypes Structure (Parker, 1995a; Galbraith, 1972; Burns & Stalker, 1961) Strategic Style (Goold & Campbell, 1987) Management style (Parker, 1995a) Interactive Control Systems (Simons, 1987) Accounting Systems (Parker, 1995a) Sub-systems Quantity of information processed (Galbraith, 1972) Human resources (Parker, 1995a) Profit centres Principal-agent relationship blurred Orientation: inward to production/professional interests Focus on inputs & reliance on state subsidies Style: reactive Organic Financial control Clear More commercial orientation with emphasis on revenue surpluses and reduced government subsidies Marketing focus Focus on outputs Proactive Several Intelligence Systems Profit planning systems Accounting - a diagnostic system AXIS – centralised Limited cost allocation Stronger accounting – an interactive system AXIS – devolved Extensive cost allocation Independent reporting systems for each entity Microcontrol and CRAMS introduced Negotiated transfer prices Reduced due to standardisation of timetable Increased due to customer and profit considerations Further increased due to addition of internal contracting High unionisation and centralised bargaining Salary gradings Decentralisation of bargaining High security of employment Voluntary redundancy programmes Lower unionisation and decentralised bargaining Performance-based reward Less security of employment 7 2.1. Interpretive schemes 2.1.1 Ownership The relationship between ownership and strategic choice is not entirely clear, although it is to be expected that different ownership forms may be associated with different managerial behaviour (Thomsen & Pedersen, 2000). The distinction between public and private ownership is a continuum of organisational types rather than a clear-cut binary division (Dunsire, Hartley, Parker & Dimitriou, 1988). Nevertheless the Railways Act, 1993, which privatised the railways, was clearly intended to ‘make new provision with respect to ... the persons by whom (railway services) are to be provided ... (and) ... to amend the functions of the British Railways Board’ (p.1). 2.1.2 Mission, goals, beliefs, values and norms One expectation of a privatised organisation is that its mission and goals will switch from a political or public interest emphasis to a commercial one (Parker, 1995a). Goals of public sector organisations are often multi-dimensional and even confused or vague; they are also externally imposed (usually by Parliament and government department) and open to repeated variation, according to political whim (Murthy, 1987). By contrast, goals in the private sector are usually based around maximising shareholder value and are largely internally set. Here the changing goals of BR, as also reflected in beliefs, values and norms (Laughlin, 1991), are characterised under the labels ‘social railway’, ‘business railway’ and ‘profitable business’. 2.1.3 Cultural paradigm Changes in organisational culture are held to be critical to the success of any privatisation venture (Dunsire et al., 1988; Parker, 1994, 1995b). Organisational culture has been the subject of an extensive literature (Pugh & Tyrrall, 2000). Siehl and Martin (1990) categorise this literature into the Integration, Differentiation and Ambiguity paradigms. In the Integration paradigm, culture is seen as an organisation-wide phenomenon, so that the organisation displays a unified purpose and set of values. In the Differentiation paradigm, researchers seek a unified purpose within each sub-unit of the organisation but not across the entire organisation. In the Ambiguity paradigm, 8 researchers do not seek consistency within the organisation, except that which emerges in response to specific issues. In this study these paradigms are used as descriptors of differing stages of cultural integration within BR. 2.1.4 Boundary systems Simons (1995) holds that these are used to indicate specific types of actions that are unacceptable within an organisation. This is of particular relevance to public sector organisations with politically driven concerns regarding equity, probity, accountability and control of public funds (Parker, 1995a). 2.2. Design archetypes 2.2.1 Organisation structure A continuum of organisational structures exist (Galbraith, 1972) ranging from functional, through matrix to divisional structures; while Burns and Stalker (1961) classify firms as mechanistic or organic. Although there is no necessary identification of the public sector with the mechanistic form (Parker, 1995a), as discussed below in the case of the railways a change from mechanistic to organic forms began. In addition, privatisation may be associated with other changes in organisational structure, including the introduction of new profit centers and a flattening of the hierarchical pyramid (Parker, 1995a). 2.2.2 Strategic style Goold and Campbell (1987) identify three major strategic styles in larger organisations. The strategic planning style emphasises centralised, long-term planning for an organisation where the portfolio of activities is very interdependent. In the financial control style, HQ allows divisions to follow independent commercial strategies, as long as they conform to budget targets. In the strategic control style, HQ attempts to strike a balance between these two courses, allowing divisions independence to pursue profitability by their own routes, while harnessing them to overall organisational objectives. 9 2.2.3 Management style In the public sector, the principal-agent relationship is potentially blurred by the intervention of tiers of state agencies (e.g. legislature, government department and corporation board) between the public, as owners/principals, and management, as agents. This, it has been suggested, is associated with an inward, production or professional focus, a reactive style (Burton & ul-Haq, 2001, p. 10), an emphasis on controlling inputs and following established procedures (the rulebook), and a processual approach to strategy (Whittington, 2001, p. 121) – all of which may reinforce a mechanistic style of organisation. By contrast, private ownership tends to be associated with a clearer principal-agent model with management incentives achieved through capital and managerial labour markets, resulting in an emphasis on outputs and a more proactive style of management. Although this summary may provide a caricature of both public and private sectors; nonetheless, it is to be expected that government policy aimed at greater commercialisation of the public sector, perhaps with a view to eventual privatisation, will lead to a different management style and possibly even new management (Parker, 1995a; Andrews & Dowling, 1998; Whittington, 2001, pp. 108-9). 2.2.4 Management control systems Simons (1987) identifies five main information-based systems in widespread use for the strategic direction of companies: profit planning, brand revenue, intelligence, programme management and human resource systems. Senior management tend use most of them diagnostically (on a management by exception basis), while using only one system on an interactive basis, taking a regular and direct interest in the information provided regardless of whether or not there is perceived to be an immediate problem or exception. The system selected for interactive use is determined by the major strategic uncertainty faced by the company or by the activity that is most critical to success. Building on Kikulis et al. (1995) emphasis on decision making as a key feature of elements of the design archetype, we argue that it is appropriate to distinguish between interactive and diagnostic systems among the design archetypes, thus allowing for both the predominance of certain systems and the possibility that control systems may change in status over time. 10 2.2.5 Accounting systems Privatisation is associated with new forms and an increased prominence of financial reporting and control to reflect the new strategic orientation and organisational structures (Andrews & Dowling, 1998). In BR AXIS was the acronym for the internal BR accounting system introduced in the 1970s, and at the commencement of this study we classify it as a diagnostic system. Parker (1995a, pp. 55-56) points out that ‘the subject of communication and reporting systems could be one of the most fruitful, but ... also one of the most problematic ... (areas) ... of research into internal change’. Such research requires access to detailed internal knowledge of the organisation and its reporting systems, something frequently denied to researchers. 2.3. Sub-systems 2.3.1 Quantity of information processed Galbraith (1972) holds that organisational design is dependent upon the amount of information the organisation has to handle, which in turn, is a function of the amount of uncertainty in the environment, the number of different elements (e.g. departments, products, etc) the organisation has to combine, and how inter-connected are the elements. Privatisation when coupled with a more market-focused approach to business, is expected to be associated with a greater need for information processing capability. 2.3.2 Human resources Commercialisation and privatisation are likely to have a significant effect on the way that human resources are managed and, in particular, on the way in which industrial relations are conducted (Pendleton & Winterton, 1993). BR was traditionally associated with high unionisation and centralised collective bargaining, but there was some erosion of this over time. Security of employment also declined in the face of organisational rationalisation. 11 3. An application to British Rail This analytical framework based on interpretive schemes, design archetypes and subsystems, is now used to assess the major changes that occurred in BR from the late 1970s until privatisation in the mid-1990s. BR was taken into state ownership immediately after the Second World War. As a ‘public corporation’ it underwent a number of changes from the 1950s to the 1970s, but remained, essentially, a highly hierarchical organisation with regional operations. From the late 1970s onwards BR’s structure changed several times. The earlier part of this period, especially the early 1980s, has been examined in Dent (1991), Gourvish (1990) and Laughlin (1991). The present paper re-examines these studies and then investigates subsequent events leading up to privatisation, drawing upon the experience of one of the authors who worked within BR during the period 1993-97, first as Finance Manager in Procurement and Materials Management (P&MM), a major division of BR, and then as a Business Performance Analyst in Group HQ. In the study, participant observation is triangulated using published studies of BR, official reports and annual accounts. The study might be regarded as a form of organisational post mortem (Orton, 1997) and as ‘an attempt to reflect upon and exercise the experiences of this author’ (Power, 1988, p. 3), whose stance was situated between that of participant observer and ‘researcherinsider and theory builder’ (Felix, 2000, p. 1). Richardson et al. (1996) also use the Laughlin (1991) framework to reflect upon a participant-observer study (also supported by documentary data), but in a smaller organisation, and with different concerns. 3.1. BR in the 1970s In BR in the 1970s the interpretive scheme can be characterised as that of ‘the social railway’ (Dent, 1991), combining: • public ownership, and hence a social or public service interest; • with an orientation towards production or professional interests; in this case ‘running a railway’ (an orientation found in other railways; Salsbury, 1994). 12 The ‘culture of the railroad’ (Gourvish, 1986, p. 577) was an integrated one (Siehl & Martin 1990) based on ‘good old soldiers falling into line’; the military metaphor dating back to the founding of the railways (Savage, 1998). The interpretive scheme was reflected in a design archetype featuring a functionally organised, mechanistic (Dent, 1991) and hierarchical organisation. Prior to 1982 the management of BR was based entirely on functional responsibilities, supported by functional directors at HQ (Managing the Railways, 1989). All significant cross-functional decisions tended to be taken at the top of the organisation by the Regional Managers, who were career ‘railwaymen’. The BR style of control was the strategic planning style (Goold & Campbell, 1987). The vehicle for this centralised, long-term but apparently somewhat unsatisfactorily executed planning (Gourvish, 1986, pp. 379-81, 503, 519) was the fiveyear corporate plan (or ‘Rail Plan’), the product of a lengthy (11-month) and complex (8 stage) annual planning process (Managing the Railways, 1989). Fundamental to BR was ‘the timetable’, a complex, highly inter-connected product. The BR approach to solving the information management problem (Galbraith, 1972) was to reduce its size and the resultant complexity through standardisation, with the result that the timetable changed very little through the years. Indeed the statutory requirement throughout this period was for ‘a public service which is comparable generally with that provided ... at present’ (Railways Act 1974; Directions by the Secretary of State 19.12.74 and 30.3.88). Little regard was given to customer type information in BR (Gourvish, 1986, p. 580). This solution to potential complexity, ie to codify it, is consistent with a mechanistic approach to managing the organisation. Such an approach can be very successful in stable markets, which feature large-scale outputs of predictable tasks in a stable environment (Burns & Stalker, 1961) and this reflected the state of affairs in BR during these years. Hence, the organisation tended to be task-oriented (Parker, 1995a; Dent, 1996) and the design archetypes, including the accounting system, reflected this. The BR accounting system, called AXIS2, treated all organisational sub-units as cost centres and only at the 2 It is revealing that the acronym connotes centralisation. 13 apex of the organisation were P&L and Balance Sheet statements derived (Dent, 1991; Gourvish, 1986, pp. 394-6, 464). BR’s Annual Reports and Accounts in the late 1970s and early 1980s provide information only on the contribution (revenue minus direct expenses) of different sectors of the business, with no attempt to allocate indirect or infrastructure costs. Accounting existed essentially for score-keeping purposes and to ensure adherence to the External Financing Limit (EFL) placed upon BR, like other nationalised industries, by Government. Hence, the accounting system was used diagnostically, rather than interactively. The organisation did not derive its purpose, its raison d’être, from the facts supplied by the accounting system (Dent, 1991) and it is for this reason that we designate the accounting system as a diagnostic rather than an interactive control system. The main interactive control systems (Simons, 1987) at HQ level in BR in this period were intelligence systems based on sustaining government and public support for BR (Gourvish, 1986, p. 575ff) as a social railway. Thus, the interpretive schemes, design archetypes and sub-systems came to form within BR a balanced or coherent whole, in an integrated culture based on providing a public railway. Peters and Waterman (1982 & 1984) and Ouchi (1981) have advocated the value of a strong culture in building employee morale and commitment; thus increasing staff potential and productivity, and in turn increasing the financial performance of the company. Despite its strong culture based on the concept of a social railway, however, BR was not renowned for its organisational excellence. The BR logo, based on arrows pointing in opposite directions, was ridiculed internally as appropriate for an organisation that did not know whether it was coming or going! Within the organisation, a judgement of one non-executive director, that BR was the ‘most deeply unimpressive organisation he had ever seen’, was widely recounted. 3.2. BR in the 1980s Environments change, delivering a disturbance to the organisation (Laughlin, 1991) so that existing policies, structures, and controls are no longer adequate and performance deviates from expectation (Hedberg & Jonsson, 1978). In the 1980s in the UK, a new interpretive scheme based on ‘privatisation’, ‘reinventing government’ and the ‘new 14 public management’ (Osborne & Gaebler, 1992; Dunleavy & Hood, 1994; Hood, 1995) was in the air. A business, profit oriented or managerial approach to public enterprises became dominant (Rose & Miller, 1992). The government began an assault upon public sector organisations, exerting pressure upon them to adopt commercial practices to increase their efficiency. The report that the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, had declared at a lunch for BR executives in 1980 that ‘any manager worth their salt would be in the private sector’ (Marston, 1997, p. 4) was widely recounted within BR. More formally, as a nationalised industry, BR had not been subject to the reporting requirements of the Companies Act; but in 1981 the Secretary of State for Transport began to require the annual accounts in Companies Act format (BR, Annual Report and Accounts, 1981, p. 36). Also, BR began to experience reductions in government subsidies as part of the Government’s policy of cutting public expenditure. It was both encouraged and forced to make up for this shortfall in revenue from passenger income and cost savings. Hedberg and Jonsson (1978) suggest that organisations in a changing environment need ‘semi-confusing’ information systems that may provide contradictory information, in order to avoid being locked into outmoded beliefs and responses. However, considerable evidence of poor performance may be required before an organisation will question or change its policies, organisation and routines in a major way. Initially, BR’s Board introduced a minor change (Dent, 1991) which was to have far-reaching consequences. Since BR visibly lacked marketing and business expertise, in 1982 the Board appointed Business Directors (BR, Annual Report and Accounts, 1982; Managing the Railways, 1989; Dent, 1991) to add an air of managerial modernity, and, more prosaically, to find a further means of extracting cash from railway customers, through a more commercial approach to operations. The Business Directors reported directly to the Board, like planning staff on an additional leg of the functional structure. The Regional Managers, however, appear to have believed that this morphostatic (Laughlin, 1991) change would make little 15 difference to their own power, position or activities (Dent, 1991). The railway would carry on essentially as before, while the marketing skills of the Business Directors would generate additional finance from the existing activities. Thus, the immediate response to the changed environment came at Board level rather than lower down the organisation, as one might expect in a hierarchical structure. In terms of its design archetype, the organisation simply enabled itself to handle more information, and hence more complexity, by increasing the volume of vertical information flows, in a slightly modified organisational structure. In time, however, the power of the Regional Managers was affected by the appointment of the Business Directors and a new emphasis on commercial goals (Dent, 1991). Business Directors discovered that the existing accounting methods provided information on their business sector revenues, but not on the associated costs. In response, an accountant was detailed to develop methods of identifying and calculating business sector costs and profits. The developing management accounting system supported a new interpretive scheme, which might be characterised as ‘the politics of profit’. Business Directors were able to use the reported figures to change the terms of reference in organisational debates. Short-term profit considerations began to displace traditional operating norms as the rationale for decision making. Rolling stock was reallocated between routes on the basis of where it could earn the most profit. Timetable alterations were introduced on the basis of the passengers the new services would attract, rather than simply the operating convenience of the timetable. Extensive track maintenance, which would normally have been done in conjunction with the associated signalling maintenance, was postponed to reduce short-term expenditure. In 1983 the Business Directors were nominated as Principal Officers on BR’s Board, signalling the displacement of the Regional Managers as the controlling force within the corporation (BR, Annual Report and Accounts, 1983). Gradually changes to the design archetypes seeped upwards through the organisation, consistent with the process illustrated in Figure 1 above. 16 In terms of Galbraith’s (1972) ‘organisation as information processor’ model, there was now more information to consider, and it flowed through two channels rather than one. For every decision, BR managers now had to consider business accounting profit information as well as the operating information they had always used. The operational information could not be ignored and consequently BR had potentially developed semiconfusing information systems (Hedberg & Jonsson, 1978). Somehow, the two sets of information had to be combined, but the existing vertical and functional structure was unequal to the task of reconciling the two different flows. BR responded by altering its organisational structure. A matrix structure was introduced from the mid-1980s, initially for financial reporting and information purposes but later extended to transform BR from a hierarchical, functionally-based organisation to a matrix form, with businesses, functions and regions forming the three axes of the matrix (BR, Annual Report and Accounts, 1987/88, p.6; Managing the Railways, 1989). The full organisation chart became known within BR as the ‘Rubik's cube’, reflecting the complex diagram circulated within the organisation to illustrate it. The organisation moved from a strategic planning to a strategic control style (Goold & Campbell, 1987) with Group HQ attempting to strike a balance between allowing business sectors independence to pursue their own goals, while harnessing them to overall organisational objectives. The Corporate Plan diminished in significance, while the accounting system, AXIS, became the main interactive control system for the running of the railway, and hence became a more prominent design archetype. AXIS was reconfigured to provide separate financial statements in Companies Act format, announcing the profitability, or otherwise, of each business sector. This even occurred within the central services, whose customers were almost entirely internal to BR. Effectiveness was no longer defined in terms of the task of train operation. It became redefined, instead, as the output of information systems focusing on commercial accounting profit. The interpretive scheme shifted to that of the ‘business railway’. 17 In terms of the public’s perception of BR’s performance, there was still evidence of a negative linkage between the new interpretive scheme and effectiveness. If operational cost is taken as the measure of effectiveness, however, the opposite conclusion may be drawn. During this period BR ran the most cost-effective railway in Europe on many measures (Shaw, 2000, p. 1), including the level of public subsidy. The level of public funding fell steadily from between 0.3% and 0.35% of GDP in 1978-85, to between 0.21% and 0.26% in 1986-88, and to between 0.12% and 0.16% in 1989-92 (BR, Annual Reports and Accounts, various dates). In 1987/88, BR reported ‘record-breaking’ results, which it attributed to cultural change and the new matrix organisation (BR, Annual Report and Accounts, 1987/88, pp. 4-6). Whether success was caused by organisational change, or simply by continued budget pressure from government, is difficult to determine. Nevertheless, these organisational and performance outcomes could be and indeed were deployed to support both the privatisation of BR (BR, Annual Report and Accounts, 1987/88, p. 7) and the retention of a nationalised railway (Modern Railways, 1988). The interpretation provided so far of BR’s development from the late 1970s could be viewed as consistent with a uni-directional approach (or drift) towards a new organisational state at all three levels of interpretive schemes, design archetypes and sub-systems. However, the morphogenetic model specifically allows for the simultaneous presence of schizophrenic elements, representing both the past and future states of the organisation at all three levels of the organisation during the change process (Broadbent, 1992). Both Dent (1991) and Laughlin (1991) acknowledge this possibility, but the weight of their evidence suggests a victory of the business railway by the mid/late-1980s. However, change within BR was not seamless. Aspects of the older interpretive schemes, design archetypes, and sub-systems survived until the public corporation’s death knell in the mid-1990s; while other parts of the organisation succumbed to the values associated with private ownership much earlier than the rest, as we indicate below. 18 Although the major privatisation of BR took place in 1995-97, creeping privatisation of parts of the railway occurred over a much longer period (Shaw, 2000, p. 46), with the result that as early as 1992 approximately one-third of the annual operating cost of BR was procured from the private sector. BR’s hotel and shipping businesses and rolling stock maintenance were privatised in the 1980s. At the level of the interpretive scheme, however, public sector boundary systems (Simons, 1995), concerning accountability and probity, endured well after the drive towards privatisation had commenced. In the Procurement and Materials Management (P&MM) division, for example, acceptance of all but minor gifts of a seasonal nature (e.g. calendars and diaries) continued to be forbidden on probity grounds. In human resources, the employee grading system and grading procedures survived, as did the role of trade unions in negotiations over wages and conditions; although there were steadily increasing redundancies throughout BR, and some shift to merit-based pay in the management grades. In the accounting system, vestiges of detailed central control survived until the demise of BR. The final set of annual accounts instructions, for 1995/96, issued by Group HQ Finance, still ran to some 161 pages. The morphogenetic model allows for such schizophrenic phenomena; but the destination is presented as an organisation with a new balance or coherence throughout its interpretive schemes, design archetypes and sub-systems (that is to say, the balance shown by IS2, DA2 and SS2 in Figure 1). The shift in interpretive scheme from social railway to business railway within BR, however, did not prove to be a force for integration either among businesses or between businesses and HQ. Rather it caused conflict. For example, a struggle over track access between the Freight and Intercity divisions was taken to Group HQ level (Dent, 1991). In Network SouthEast, the Business Manager had stations and rolling stock refurbished in a new livery (BR, Annual Report and Accounts 1986/7, p. 20), in defiance of both traditional railwaymen and cost conscious HQ accountants, who tended to view such activities as an unnecessary extravagance. Thus, insofar as colonisation did result in a new organisational coherence, it was not exhibited at Board level but at divisional level, with a differentiation paradigm prevailing among the businesses. 19 The matrix organisation can simply become a staging post during change in either direction between functional and business organisations (Galbraith, 1972), and indeed in BR the matrix organisation proved to be an unstable state. The quantity of information to be handled exceeded the matrix structure's capacity. Liaison meetings proliferated and continued to do so even as internal contracts, which theoretically should have reduced the need for liaison meetings, became widespread (MMC, 1987). The question, of course, was how the potential instability in the organisation would be resolved. For BR, the fate of the structure was sealed by the Clapham Junction rail accident in December 1988. The subsequent Hidden Report (November, 1989) attributed blame to problems ‘historic to the railway culture and method of organisation’ (cited in Brown, 1989, p. 26). Arguably this undermined one of the core claims of the ‘social railway’, namely its ability to ‘run a safe railway’, and highlighted a need for large-scale spending on rail safety, including the expensive Advanced Train Protection system (both of which were to encourage a cost-conscious government to lean towards privatisation). BR’s Board accepted the Hidden Report’s findings and recommendations in full (Brown, 1989; BR, Annual Report and Accounts 1988/89, p. 3; BR, Annual Report and Accounts 1989/90, p. 4): ‘(L)ying behind the accident ... was a whole chain of circumstances that has everything to do with management responsibility’ (Sir Bob Reid, Chairman of BR, 1993, quoted in Hurst, 1998, p. 7). The organisational design archetype emerging from the morphogenetic colonisation had become unwieldy and decentralisation seemed to be the solution (BR, Annual Report and Accounts, 1988/89, p. 7). 3.3. BR in the 1990s The 1990s were characterised by a quite different morphogenetic process with a quite different outcome. At first this was not apparent. In 1990 the BR design archetype was transformed during the ‘Organisation for Quality’ initiative (BR, Annual Report and Accounts, 1990/91, p. 11) into a divisional structure involving the following separate business divisions: Intercity, Network SouthEast, Regional Railways, Parcels, RailFreight Distribution, Central Services, with each sub-divided into different 20 businesses. This restructuring marked the end of the line for the six railway regions that had prevailed in BR since nationalisation. The aim was to simplify the organisational structure, enhance effectiveness and hence improve the organisation’s self-image. The campaign met with a cynical response from the lower ranks within BR, however. ‘Organisation for Quality’ was shortened to ‘O for Q’ (Shaw, 2000) for presentation purposes, but was widely mispronounced (to sound like ‘oh, f--- you’), as an indication of what many felt was the Board’s attitude to the work force. This episode demonstrates that interpretive schemes may spring to life regardless of management intentions, illustrating that ‘no one has a monopoly on meanings’ (Dent, 1991, p. 709)! The divisional structure was able to handle greater amounts of information than the functional structure, and most cross-functional decisions did not rise above divisional level. In a divisional structure, HQ assesses the effectiveness of its divisions on the outputs they achieve, rather than attempting to regulate task details (Dent, 1996). BR followed this pattern closely, giving ‘managers ownership and bottom-line responsibility for the assets they use and mov(ing) responsibility for decision-making as close as possible to the customer’ (BR, Annual Report and Accounts, 1990/91, p. 11). BR’s strategic style moved to one of financial control (Goold & Campbell, 1987). Group HQ used profit-planning systems as the interactive system to enforce conformity to divisional budget targets. A PC based management accounting reporting package, called Microcontrol3, was installed to enable Group HQ to collate actual versus budget data for the new entities created. Internal contracts between business divisions replaced administrative decisions as a means of co-ordination. An internal Contract Recording and Monitoring System (CRAMS) was set up, specifically incorporating a contract dispute and arbitration procedure. The effect was to reinforce the differentiation paradigm within BR, such that, at least in the management ranks, identification was with the division as much as with BR. Many of the businesses, and even sub-units, developed individual and profit-related missions, along with vision, value and strategy statements. The introduction of a 3 Again the connotations of the system name are revealing. 21 differentiation culture also caused differences in the interactive control systems used at divisional level. For example, the passenger businesses used brand revenue systems as their interactive systems; while P&MM, as an internal service division, used a customer contracts/receivables system interactively. Thus, any new organisational balance or coherence was achieved at divisional rather than organisational level – a change pathway that can be termed ‘fragmentation’. The Thatcher governments of the 1980s had rejected railway privatisation as being both too difficult and politically unacceptable (Shaw, 2000, p. 47 and 56). But, in effect, the apparent success of the new interpretive scheme within BR enabled the Major government, after 1990, to contemplate the privatisation of BR. Following the passage of the Railways Act (1993), the organisational form selected for BR’s privatisation accelerated fragmentation and accentuated differentiation within BR. The major businesses were divided into over 80 smaller businesses (partially based on O for Q divisions; Shaw, 2000) in preparation for sale. BR’s Board now had several inter-linked objectives, including preparing businesses for privatisation, reducing staffing, maintaining revenues, and managing government relations, while continuing to meet the EFL. Organisations in crisis may need to use several systems interactively when there is more than one critical success factor to be monitored (Simons, 1987). Each week the Board received a ‘flash report’ on passenger revenues, employee numbers, and progress towards EFL targets, while a newspaper cuttings service circulated press reports daily. Following this major restructuring, the Board were unable to contain BR’s centrifugal tendencies. The same held at divisional levels. The Director of Central Services held a two-day conference in an attempt to interest his divisional managing directors and finance directors in a central services plc; while the MD of P&MM division developed a scheme to preserve P&MM as an entity. The tide was against such centralising initiatives. The new infrastructure business, Railtrack, embarked on a year-end spending spree just before its separation from BR, and after separation attempted to increase its share of the industry EFL at the expense of the remainder of BR. Rolling Stock Leasing Companies and the Infrastructure and Signalling Maintenance Units were reluctant to 22 abide by EFL targets and reporting deadlines. Disputes over unpaid internal invoices climbed swiftly to over £100m and were only resolved by central diktat. Eventually even the Train Operating Units proved recalcitrant. The MD of Scotrail had his budgetary disagreements with BR’s Board published in the Glasgow Herald (17 February, 1995, p. 1) and then tendered his resignation. Chiltern Railways were accused of attempting to defraud London Underground of passenger revenues on a shared route. Within the accounting system, AXIS, business sector reporting in the annual accounts became impossible (BR, Annual Report and Accounts, 1994/95, p. 51). New and separate accounting systems had to be purchased for all the various parts of BR, in order to prepare them for privatisation. Privatisation split the railway into numerous companies, many of which have since been subsumed into other organisations. The railway became a disparate group of businesses, with only a common railway pension scheme and a common trade association linking them. The cultural paradigm became that of ambiguity with scope for internal agreement only on specific issues. Market prices for track access, rolling stock leasing, etc provided the decision criteria. This reduced the amount of information to be handled by any individual operation. Furthermore, an element of slack was introduced into the system. For a period, the new interpretive scheme, ‘profitable business’, seemed more acceptable for attracting subsidy from government than the old interpretive scheme, ‘social railway’. Today the privatised railway receives significantly higher government subsidies than the public railway did (Modern Railways, 2001a & b) although recent government intervention in Railtrack, following government dissatisfaction with that company’s management, means that the interpretive scheme underscored by privatisation may in turn be under threat. 4. Discussion and conclusions This study uses the BR case to illustrate how structural contingency modes of analysis may be used to provide additional conceptualisation called for by Laughlin (1991) for the modeling of organisational change. The contingency models do seem to add explanatory power to the model, especially in its application to a large organisation. 23 Within BR, discernible relationships were displayed between certain interpretive schemes, design archetypes and subsystems. These outcomes seem to be those which might be expected or predicted by the adapted Laughlin models, as set out in the earlier part of the paper. However, the relationship between these organisational features and the degree of integration, differentiation or ambiguity within the organisational culture, while perhaps not unexpected, does illustrate two additional pathways of change, which we term a ‘fragmentation’ pathway and an ‘imposed evolution’ or ‘revolution’ pathway. The evocation of the ‘business railway’ by the Board of BR made it possible to attribute organisational successes (such as increasing financial self-sufficiency) to permeation by the new interpretive scheme, and failures (e.g. the Clapham Junction accident) to the lingering effects of the old interpretive scheme (social railway). However, the resulting balance or coherence was not achieved at organisational level (an integration culture), but at lower levels of the organisation. The creation of business units introduced a differentiation culture, in which identification tended to be with the division rather than BR. These schizophrenic elements were not resolved (pace Dent and Laughlin), but created continuing divisive tensions, and ultimately fragmentation. Explaining the enactment of privatisation of BR during the 1990s appears to require a top-down and externally imposed pathway, which is clearly a possibility in any event that changes ownership. We term this imposed evolution or perhaps revolution.4 The structure of the privatised railway was not one envisaged or welcomed by BR’s board. New design archetypes corresponding to the interpretive scheme of a profitable business were imposed upon the railway. This heightened the degree of internal differentiation, since organisational units were judged on their individual performance, thus increasing organisational rivalry and problems of central control while they remained under the aegis of BR. 4 Internal discussions of organisational change during the period 1993-6 tended to emphasize the need for ‘evolution rather than revolution’, when in fact, of course, the organisational changes were major ones. 24 From the BR evidence, neither functional nor divisional structures (design archetypes) have any necessary identification with ownership (public or private sector) or organisational performance. Organisational change and performance improvement preceded the transfer from the public to private ownership (something found for some other privatisated enterprises in the UK; Martin & Parker, 1997), but in reforming the organisation, BR’s Board prepared an organisation amenable at all three levels (Laughlin, 1991) to the divisive form which privatisation took. This raises the issue of why rebuttal, or even reorientation, may not work as an organisational response to an environmental disturbance. Within any organisation, it may be easier and more effective for management to change lower levels of organisational phenomena (whether sub-systems or design archetypes), and hence change the interpretive schemes indirectly, than to attempt directly to change the interpretive schemes (Pettigrew, 1990)5. One implication of this argument is that an attempt to change the lower levels alone may not be so limited in its effect, especially when the changes are laden with a new interpretive scheme. This tends to confirm Parker’s (1995a) speculation on the importance of reporting and control systems in internal change, but specifically directs attention to the interconnectedness of subsystems, design archetypes and interpretive schemes. It also implies that some design archetypes may be incompatible with some interpretive schemes. At a policy level, on the basis of BR's experience such concerns may be especially relevant during organisational changes pursuant of privatisation. Changes to the interpretive scheme are to be expected, but the nature of the prevailing interpretive scheme may be critical to organisational success. This problem is exacerbated by the difficulty of measuring the impact of interpretive schemes upon organisational effectiveness. It also highlights the risks involved in imposing evolution (revolution) upon an organisation for exactly the same reasons. 5 Pettigrew (1990: 266) expresses this using different terminology: it is ‘easier to adjust the manifestations of culture than it is to change the core beliefs and assumptions’ directly. 25 A number of the changes reported in this study possibly have parallels in other public sector organisations in Britain during the 1980s and 1990s, including some that remained in the public sector, such as government departments and the Post Office. Therefore, the relationship between the organisational and strategic changes discussed and privatisation is not necessarily clear-cut. Further research based on such organisations could usefully extend both the conceptualisation and the application of the morphogenetic model. Nevertheless, it seems clear that in BR, without the earlier change to a more commercial culture and supporting organisation and control systems, privatisation would have been both less tempting and less feasible for government. References Andrews, W.A. and Dowling, M.J. (1998) ‘Explaining performance changes in newly privatized firms’, Journal of Management Studies, vol. 35, no. 5, 601-617. Bös, D. (1991) Privatization: A Theoretical Treatment, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Boycko, M., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R.W. (1996) ‘A Theory of Privatisation’, Economic Journal, vol. 106, March, 309-19. Broadbent, J. (1992) ‘Change in organisations: a case study of the use of accounting information in the NHS’, British Accounting Review, vol. 24, no. 3, 343-67 Broadbent, J. and Laughlin, R. (1998) ‘Resisting the “new public management” Absorption and absorbing groups in schools and GP practices in the UK’, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, vol. 11, no. 4, 403-35. Brown, K. (1989) ‘Bleak Signals for the Future’, Financial Times, Wednesday, 8 November, p. 26. Burns, T. and Stalker, G.H. (1961) The Management of Innovation, London: Tavistock. Burton, J. and ul-Haq, R. (2001) ‘Strategic Management of Privatisation Methodology. Part 1: Improving strategic management in privatizing firms: The Divergency SchemaTM’, Working Paper Series 2001-15, Birmingham Business School, University of Birmingham. Clark, E. and Soulsby, A. (1995) ‘Transforming former state enterprises in the Czech Republic’, Organization Studies, vol. 16, no. 2, 215-42 26 Cooper, D., Hinings, B., Greenwood, R., and Brown, J. (1996) ‘Sedimentation and transformation on organisational change: The case of Canadian law firms’, Organization Studies, vol. 17, no. 4, 623-47. Dent, J.F. (1991) ‘Accounting and Organizational Cultures: A field study of the emergence of a new organizational reality’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 705-732. Dent, J.F. (1996) ‘Accounting and Organisations: A review essay’, in Warner, M. (ed.) International Encyclopaedia of Business and Management, London: Routledge. Dunleavy, P. and Hood, C. (1994) ‘From Old Public-Administration to New Public Management’, Public Money and Management, vol. 14, no. 3, 9-16. Dunphy, D. and Stace, D. (1988) ‘Transformational and coercive strategies for planned organisational change: beyond the O.D. model’, Organization Studies, vol. 9, no. 3, 317-34. Dunsire, A., Hartley, K., Parker, D. and Dimitriou, B. (1988) ‘Organisational Status and Performance: a conceptual framework for testing public choice theories’, Public Administration, vol. 66, winter, 363-88 Felix, E. (2000) ‘Creating Radical Change: Producer choice at the BBC’, Journal of Change Management, vol. 1, no. 1, 5-21. Galbraith, J.G. (1972) ‘Organisation Design: An information processing view’, in Lorsch, J.W. and Lawrence, P.R. (eds) Organisation Planning: Cases and Concepts, Homewood, Ill: R. D. Irwin. Goold, M. and Campbell, A. (1987) ‘Many Best Ways to Make Strategy’, Harvard Business Review, vol. 65, no. 6, 70-76. Gourvish, T.R. (1986) British Railways 1948-73: A business history, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gourvish, T.R. (1990) ‘British Rail’s “Business-Led” Organization, 1977-1990: Government-industry Relations in Britain’s Public Sector’, Business History Review, vol. 64, Spring, 109-149. Hedberg, B. and Jonsson, S. (1978) ‘Designing Semi-Confusing Information Systems for Organizations in Changing Environments’, Accounting, Organizations, and Society, vol. 3, no. 1, 47-64. 27 Hood, C. (1995) ‘Contemporary Public Management: A New Global Paradigm?’, Public Policy and Administration, vol. 10, no. 2, 104-17. Hurst, N.W. (1998) Risk Assessment: The Human Dimension, London: Royal Society of Chemistry. Kikulis, L., Slack, T., and Hinings, C. (1995) ‘Sector-specific patterns of organisational design change’, Journal of Management Studies, vol. 32, no. 1 (January), 67-100. Laughlin, R. (1991) ‘Environmental Disturbances and Organizational Transitions and transformations: Some alternative models’, Organization Studies, vol. 12, no. 2, 209-232. Laughlin, R., Broadbent, J., Shearn, D., and Willig-Atherton, H. (1994a) ‘Absorbing LMS: The coping mechanism of a small group’, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, vol. 7, no. 1, 59-85. Laughlin, R., Broadbent, J., and Willig-Atherton, H. (1994b) ‘Recent financial and administrative changes in GP practices in the UK: Initial experiences and effects’, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, vol. 7, no. 3, 96-124. Lawrence, P.R. and Lorsch, J.W. (1967) Organization and Environment, Boston, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Managing the Railways (1989). Internal BR document produced by the Director, Financial Planning. London: BR Board. April. Marston, P. (1997) ‘Scottish Expresses Signal the End of the Line for British Rail’, Daily Telegraph, Tuesday 1 April, 4. Martin, S. and Parker, D. (1997) The Impact of Privatisation: ownership and corporate performance in the UK, London: Routledge. MMC (1987) Report into Network Southeast, London: HMSO. Modern Railways (1988) ‘Editorial’, August, 393. Modern Railways (2001a) ‘Railtalk’, April, 4. Modern Railways (2001b) ‘Railtalk’, May, 4. Murthy, K.R.S. (1987) ‘Do Public Enterprises Need a Corporate Strategy’, Vikalpa, vol. 12, no. 2, 9-19. 28 Orton, J.D. (1997) ‘From Inductive to Iterative Grounded Theory: Zipping the gap between process theory and process data’, Scandinavian Journal of Management, vol 13, no. 4, 419-38. Osborne, D. and Gaebler, T. (1992) Reinventing Government, Reading, Mass.: Addison Wesley. Ouchi, W.G. (1981) Theory Z: How American business can meet the Japanese challenge, Reading, Mass.: Addison Wesley. Parker, D. (1994) ‘Privatisation and the International Business Environment’, in SegalHorn, S. (ed.) The Challenge of International Business, London: Kogan Page, pp. 175-97. Parker, D. (1995a) ‘Privatisation and the Internal Environment’, International Journal of Public Sector Management, vol. 8, no. 2, 44-62. Parker, D. (1995b) ‘Privatisation and Agency Status: Identifying the Critical Factors for Performance Improvement’, British Journal of Management, vol. 6, 29-43. Pendleton, A. and Winterton, J. (eds) (1993) Public Enterprise in Transition: Industrial Relations in State and Privatized Companies, London: Routledge. Pennings, J.M. (1992) ‘Structural Contingency Theory: A reappraisal’, Research in Organizational Behaviour, vol. 14, 267-309. Peters, T.J. and Waterman, R.H. (1982) In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s best-run companies, New York: Harper and Row. Peters, T.J. and Waterman, R.H. (1984) Who's Excellent Now?, New York: Harper and Row. Pettigrew, A. (1990) ‘Is Corporate Culture Manageable?', in Wilson, D. (ed.) Managing Organisations, New York: McGraw-Hill. Popper, K. (1979) Objective Knowledge: An evolutionary approach, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Power, M. (1988) ‘Educating Accountants: Towards a Critical Ethnography’, 2nd Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Accounting Conference, vol. 3, University of Manchester 11-13 July. Pugh, D.S. and Hickson, D.J. (1976) Organisational structure in its context: the Aston programme 1, Farnborough: Saxon House. 29 Pugh, G. and Tyrrall, D. (2000) ‘Culture, productivity and competitive advantage’, Economic Issues, vol. 5, no. 3, 5-25. Richardson, S., Cullen, J., and Richardson, B. (1996) ‘The story of a schizoid organisation: How accounting and the accountant are implicated in its creation’, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, vol. 9, no. 1, 8-30. Rose, N. and Miller, P. (1992) ‘Political Power Beyond the State: Problematics of Government’, British Journal of Sociology, vol. 43, no. 2, 173-205. Salsbury, S. (1994) ‘The Passenger Train in the Motor Age: California’s Rail and Bus Industries’, Business History Review, vol. 69, no. 1,155-7. Savage, M. (1998) ‘Discipline, Surveillance and the Career Employment on the Great Western Railway 1833-1914’, in McKinlay, A and Starkey, K. (eds) Foucault, Management and Organisation Theory, London: Sage. Schein, E.H. (1984) ‘Coming to a New Awareness of Organizational Culture’, Sloan Management Review, vol. 25, no. 2, 3-16. Shaw, J. (2000) Competition, Regulation and the Privatisation of British Rail, Ashgate, Aldershot, England. Siehl, C. and Martin, J. (1990) ‘Organizational Culture: A key to financial performance’, in Schneider, B. (ed.) Organizational climate and culture, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Simons, R. (1987) ‘Accounting Control Systems and Business: An empirical analysis’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, vol. 12, no. 4, 357-374. Simons, R. (1995) ‘Control in an Age of Empowerment’, Harvard Business Review, vol. 73, no. 2, 80-88. Slack, T. and Hinings, B. (1994) ‘Institutional pressures and isomorphic change: an empirical test’, Organization Studies, vol. 15, no. 6, 803-827. Thomsen, S. and Pedersen, T. (2000) ‘Ownership Structure and Performance in the Largest European Companies’, Strategic Management Journal, vol.21, no.6, 689705. Vickers, J. and Yarrow, G. (1988) Privatization: an Economic Analysis, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 30 Whittington, R. (2001) What is Strategy – and does it matter?, 2nd ed., London: Thomson Learning Wilmott, R. (2000) ‘The Place of Culture in Organisation Theory’, Organization, vol. 7, no. 1, 95-128. 31